Teachers no matter what forms of pedagogy they engage have usually been concerned to evaluate the learning of their students. The historical tendency, especially in the last two hundred years has been to formalise the process. Written tests and examinations have mainly displaced oral displays of achievement. Concentration on the testing of individual mastery has tended to displace interest in collective achievement, though the latter was resurgent from the late twentieth century as nation states collected data especially on the literacy and numeracy of cohorts of young people at different stages of their school education. Evaluating student mastery of a curriculum has been increasingly centralised and bureaucratised. State departments of education, universities and examination boards have tended to assert control, displacing the previous authority of teachers and individual schools. Success by individuals in formal assessments is often converted into credentials (certificates, diplomas and degrees). Such credentials have often been valued in labour markets. In different historical eras some credentials became essential for advancement into colleges of higher education, and/or employment in a variety of occupations. This historical process has been complex and long. These emerging relationships between learning, assessment and credentials have long been contested.

Four ways of thinking about school assessment practice

As a technical question

Assessment of student work is often regarded as a technical question, where ways of assessing students more efficiently, accurately, and fairly are sought. For example, how reliable can assessors of essays in the humanities be? (Is double or triple marking by different people a safeguard?) How can luck be minimised in multiple choice answers? Is continuous assessment fairer than summative? How useful are highly prescriptive statements about what compose different achievement standards? Should various disabilities, social, mental and physical, affect the assessment process, and how?

As a philosophical question

If aspects of progressive educational thinking are taken seriously, then high stakes assessment may be argued as inimical to safe and creative learning environments. Some assessment regimes may favour superficial student performance, outweighing deeper and more authentic learning. At various times in history moral character and behaviour have impacted assessments. (A modern example of this: ‘Should regular class attendance be a factor affecting grades or passing?’) Is it ethical to fail or pass students, disregarding their individual learning circumstances? Is it ethical or irresponsible not to fail students in some circumstances?

As a question for psychology

Over the twentieth century through to the present day the discipline of educational psychology has taken a great interest in what might constitute natural and acquired intelligence, and how learning takes place. At various times the social administration of consequent psychological conclusions have affected the sorting and selecting of students for different educational experiences, and have led to scepticism about common or standard instruments that purport to test student learning.

As a political and sociological question

Students with highly educated middle class parents tend to succeed more consistently in the assessment tasks valued by main-stream schools. Some sociologists have argued that the assessment and credentialling regimes engaged by the state and powerful educational institutions unfairly advantage the already advantaged. (To address this, some schools and universities set aside places and/or scholarships that recruit from so-called disadvantaged communities.) Some assessment and credentialling practices may be about the consolidation of the prestige and power of already powerful institutions and communities.

Historical emergence of merit as a factor determining professional competence and social leadership

(a) Feudal patterns

Birth into certain families or ‘blood’ was the common means of identifying the ‘best’ persons for leadership in many European societies. Patriarchal regimes favoured older and male persons. The church in mediaeval times, and later, may have taken some trouble to identify clever boys from poor backgrounds for some roles, but leaders of the church usually came from the same aristocratic families who dominated other parts of society. Social cohesion, everyone ‘knowing their place’ was the key to understanding this kind of society. Clever persons from the peasantry were likely seen as potential rebels rather than social assets. The teaching of literacy in particular was often restricted for such persons. The proving of merit through educational attainments was usually ill-regarded in comparison with inherited status.

(b) Capitalism, bureaucracy and the middle class

By the eighteenth century in western Europe, feudal patterns were challenged. An emergent middle class, whether involved in law and administration, or trade and industry, was increasingly unsettled by the disparity between their growing wealth and the traditional power of aristocracies. A demand, increasingly strong in France and England by the early nineteenth century was that ‘career should be open to talent’ or merit. This was revolutionary. In England the way one had become an officer in the army was to ‘buy’ a commission; the way one became a public servant was through ‘patronage’. By the late nineteenth century, recruitment to government employment increasingly occurred through civil service examinations and the credentials they supported. ‘Merit’ not ‘birth’ was fought for and seen as a superior way to identify the best potential employees. Businesses, increasingly reliant on large numbers of clerks, also moved in this direction. The chance to prove ‘merit’ or ‘ability’ regardless of social class background, let alone racial, gender and other characteristics for preferment, including in employment, has been a long and continuing struggle. Proof of merit through educational achievement became highly significant in this process.

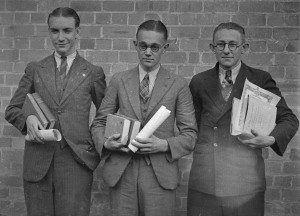

Young men being examined on theory in mechanics. 1946. Source: State Library of Victoria.

(c) Modernity and credentialism

The rise of a so-called ‘meritocracy’ paralleled the rise of the credential and credentialism as educational and social phenomena. At the end of a course of study, successfully completed, came a ‘credential’. This credential could be traded in a labour market, although unlike some other bartering systems, a credential could often hold its value for the holder beyond the gaining of one job or place. Employing, promoting or rewarding people on the basis of their credentials helps define modernity. At the same time the process has not been without problems. As more people have recognised the power of credentials to improve their prospects, there has often been credential ‘devaluation’, and its partner, credential creep. (To be a school teacher in the late nineteenth century one was usually ‘apprenticed’ as a ‘monitor’ or ‘pupil teacher’ in a school, perhaps certificated eventually, passing a minimal number of exams relating to school curricula, and possibly spending no time at all or less than half a year in a ‘normal school’ or teachers college. Now, for a similar job, one needs a four year university degree.)

(d) Pervasiveness of credentialism

In countries like Australia, the segment of the labour market which does not require educational credentials is contracting rapidly. More young people are becoming dependent for their economic survival on gaining credentials. Therefore, the assessment practices that are used and the way they are used are significant social issues. We see this in the never-ending debate over the role of school completion certificates in the Australian states: ‘Whom do they reward?’, ‘Whom do they fail?’ ‘What knowledge and skills should be tested?’ ‘How can knowledge and skills be reliably tested?’, ‘Who should compose and control the various testing authorities?’ ‘How should employers and higher education institutions use school completion results?’, ‘Should proof of educational success be supplemented or replaced by portfolios proving significant experiences, achievements and attitudes unrecognised by school or college results and credentials?’ and ‘Should successfully completed internships, paid or unpaid, form a necessary part of any awarded credential?’.

Some sectors of the labour market remain resistant to educational credentials. They include the diminishing numbers of unskilled labouring and operative jobs. Small family businesses often employ on the basis of family connection rather than educational merit. The phenomenon is not unknown in larger corporations, where family and other networks, including having attended certain schools (the ‘old school tie’), often play a part in leadership recruitment.

1780s to the 1850s

Early in this period, testing the achievement of students was mainly the work of teachers. In many institutions, especially those of larger size and with public responsibilities, there were further assessments of the work and success of schools. This might occur through the work of official visitors. In the early history of New South Wales, some of the governors undertook such work. The virtuosity of students was displayed, often through oral presentations and questioning. Sometimes written work would be displayed. There was probably less interest in the achievements of individuals than collective achievement, and this was expected to reflect well or otherwise on the teachers or the school. Students were focused on rote learning their topics. Recitations were meant to impress the audience. Such performances were well rehearsed. In a later period, such approaches to student and school assessment and examination would be considered deeply flawed.

The influence of monitorialism in teaching had the effect of collecting students of roughly the same attainment, especially in reading, into groups within a school. They might then be taught collectively and efficiently. The making of such homogeneous groups for efficient teaching certainly involved an assessment of individuals’ attainments.

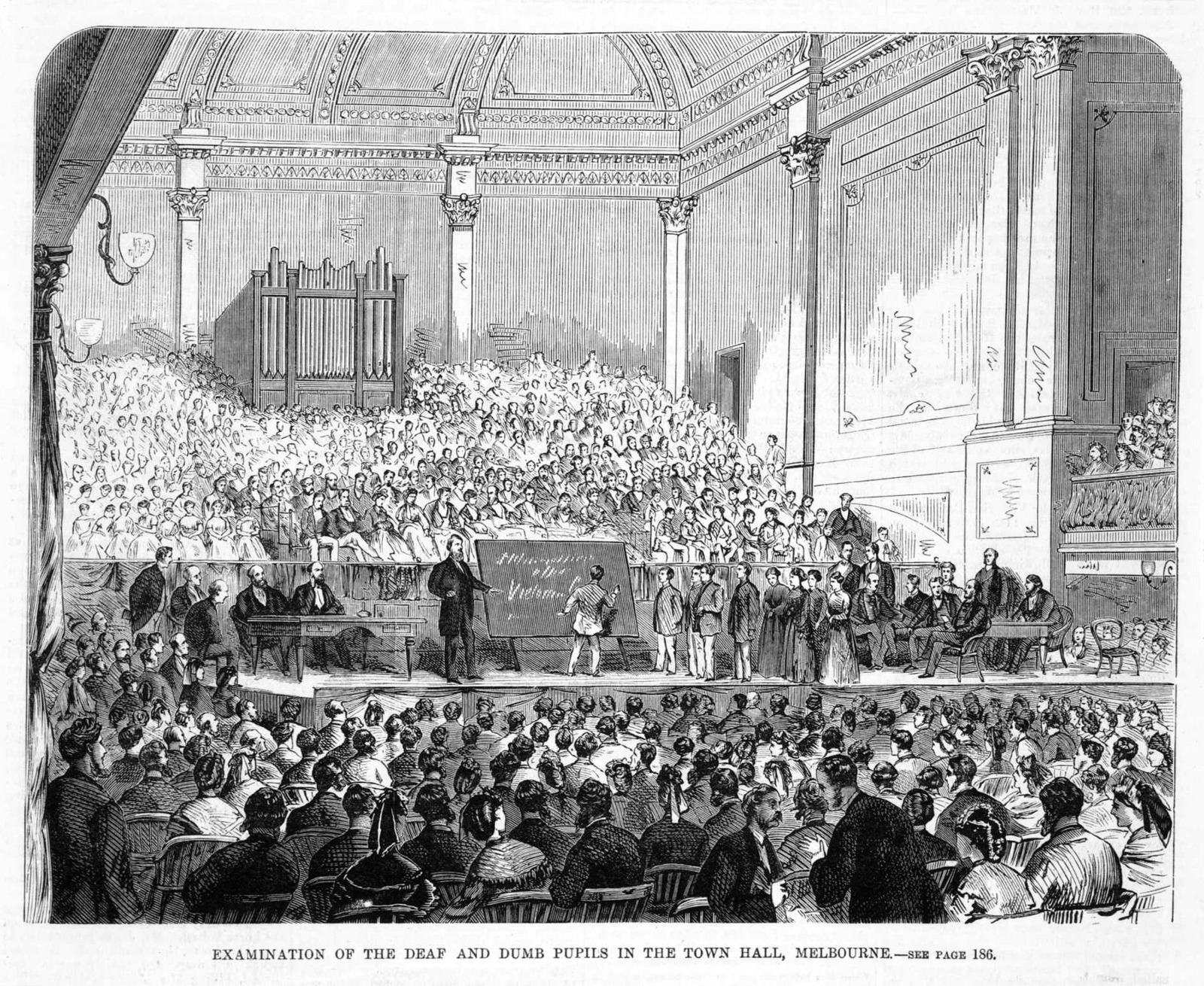

People who might undertake the work of visiting schools and assessing the work of students and teachers might include local clergymen and/or civic leaders. This visiting was not likely to occur more than once or twice a year. Often the process was public, with parents and other members of a community invited to witness the performances and displays. Such events were not limited to regular schools. The Sunday School anniversaries of many protestant denominations preserved and promoted such displays well into the twentieth century.

In the 1820s school principal, Lawrence Halloran, was conducting half-yearly and yearly public examinations for large numbers of students in his predecessor to Sydney Grammar School. He challenged other schools to send boys to compete against his boys, and invited the public to witness the displays. The potential usefulness of pupil examinations, conducted in public, as advertisements for school excellence was established early.

A late example of an old style public examination in Victoria, 1871. Source: State Library of Victoria.

Well before the middle of the nineteenth century there was some professionalisation and regularisation of the roles of school visitors and inspectors. The Church and Schools Corporation for example appointed an Inspector General not only to organise schools but to inspect their work. Later the National and Denominational school boards that operated in New South Wales, and later in Queensland and Victoria from the 1840s, also appointed inspectors of schools. School board inspectorates developed tables of standards around which curricula and teaching were organised. Consistency of approach and application, and success in achieving the standards were limited. Contributing to this were the wide variability in the training of teachers, the existence of large numbers of tiny and remote one-teacher schools, and the want of strong regulations concerning student attendance at schools.

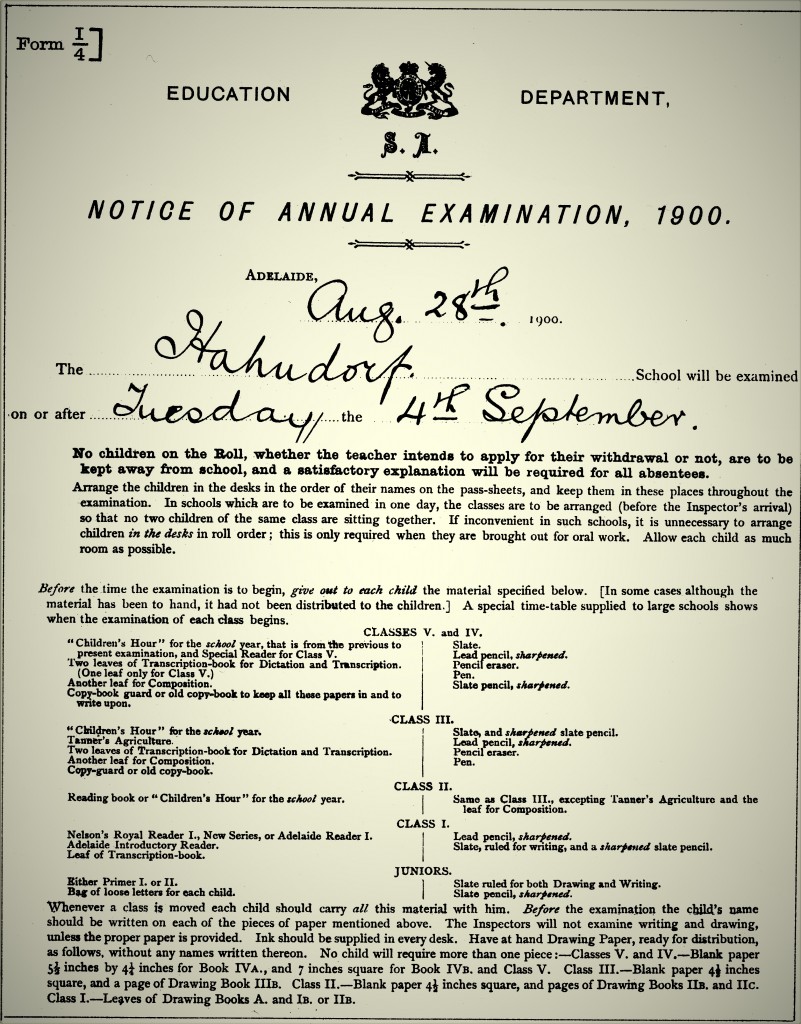

In the era of local, then colony-wide boards managing schools and systems of schools, there were regulations requiring some kind of testing of students. This from 1860 in South Australia was minimalist in approach: “Teachers are required to hold a public examination of their pupils during each year, of which at least fourteen days’ notice must be given to the Board” (Hyams et al., p. 53). Content of examination and procedures were not specified, in this regulation at least.

For most families in this period, prolonged school attendance was a low priority in comparison with the requirement that children contribute to the labour that kept household economies viable. From the 1860s, as the management of schools began to be controlled by state departments of education the testing and examination of students was increasingly formalised. The desire to produce testing regimes that allowed comparison between students from different schools saw an increasing replacement of oral examinations with written tests.

1860s to the 1920s

There were two powerful sets of institutions that made a start on regularising and bureaucratising school assessment regimes from the 1860s.

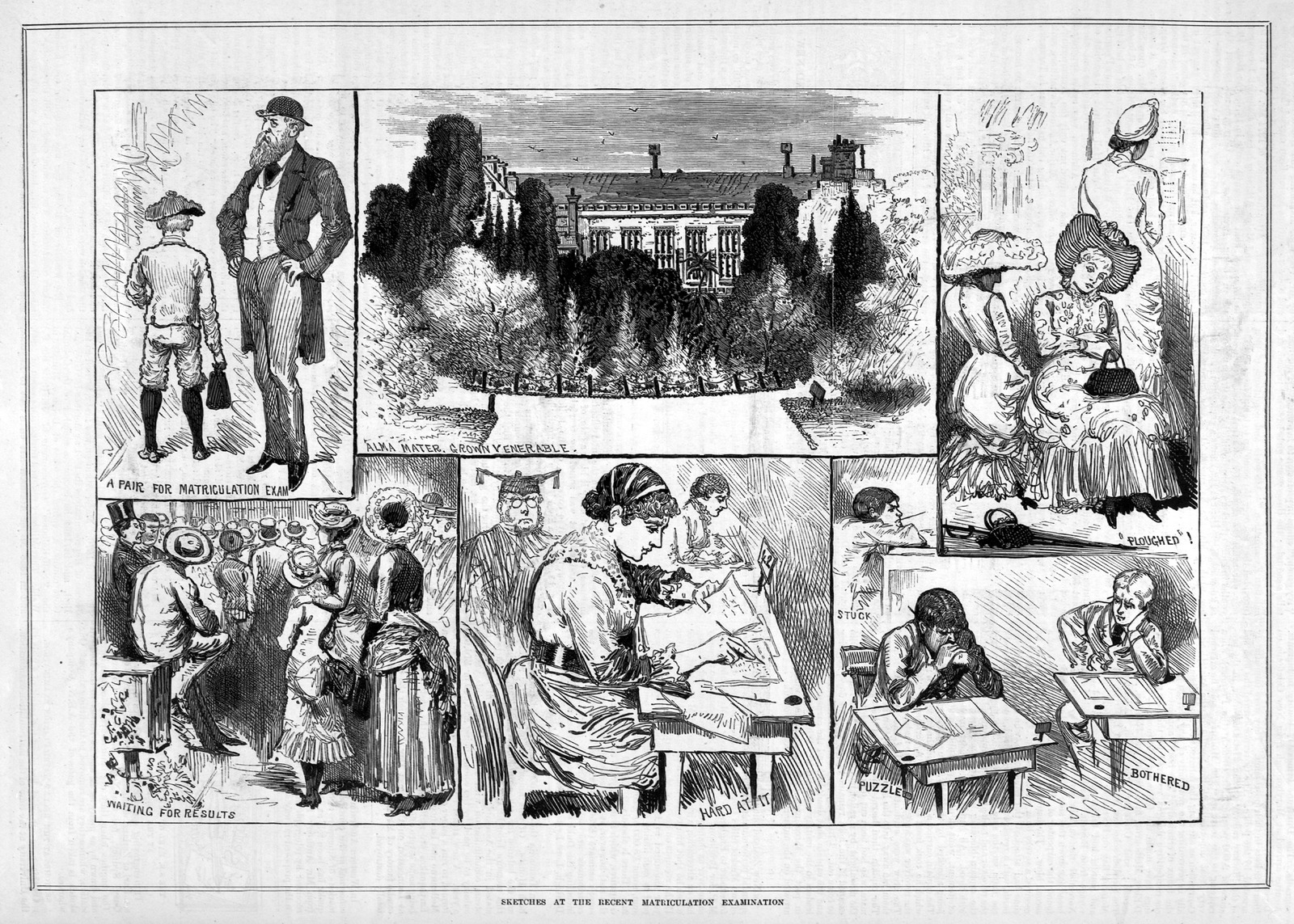

First was the interest from the colonial universities, Melbourne and Sydney, established in the early 1850s, in setting matriculation examinations for students seeking to enter their degree programs. The numbers of students involved were very few in the nineteenth century, but the universities grew in prestige nevertheless. Quite rapidly their professorial boards represented themselves as legitimate authorities not only regulating entrance to their own institutions from the early 1850s, but demanding that post-elementary schools accept their interest in formulating subject syllabuses and assessment practices, written examinations, that would lead towards matriculation. At the University of Melbourne matriculation subjects began with Latin, Greek and mathematics, then English history and geography, and in 1862, French and German. In 1871 girls were allowed to sit the matriculation examinations. In Sydney girls were allowed to present for public examinations in the same year.

Contemporary comment on sitting the University of Melbourne’s matriculation exam. Girls included. 1884. Source: State Library of Victoria.

Second was the interest of the colonial governments in establishing public education systems through the education acts of the 1870s (the ‘free, compulsory and secular’ acts). Associated with their establishment was the rapid development of colonial inspectorates. Their reach and authority spread as they laid down subject syllabuses, attainment standards and assessment regimes. To support this, public (later known as primary) schools instituted regular, often weekly tests, especially in the various subjects which would later be grouped under the terms, literacy and numeracy. The annual testing of students would determine student promotion to the next standard or class. There was little regard for keeping students of the same age together, as a reason for advancement to the next class or grade. Children were held back if they could not meet the prescribed standards. Those who failed to meet the standards were expected to leave school as soon as they were able.

A further extension of this development in public education systems was the adaptation of the English Revised Code in Australian colonial schools. Otherwise known as payment by results, teachers’ salaries and promotions were made dependent in part on the results their students gained in the various examinations and inspections. Critics were vocal soon enough. Inspector Whitham in South Australia reported in 1902:

the result examination … has done more to stamp out the individuality of the teacher than anything else. Instead of following out his own lofty aspirations as to the best means of promoting the interests of his pupils, he has had to conform to the system of examination in all its harassing details … the teacher has generally become mechanical in his work …the moral training of the pupils has suffered in consequence. (Quoted in Hyams et al., p. 139)

Meanwhile the universities reached deeper into the post-elementary schools, establishing public examinations and credentials for each stage of this education, soon to be known as secondary education. Public high schools, private, church and secular schools and colleges entered students for end-of-year examinations, commonly named the Primary, Junior and Senior. Certificates were issued by the universities for those who passed. Success in the Senior examination usually constituted matriculation for the universities.

Early in this period the development of public examinations was usually welcomed in schools, especially those that attracted sufficient numbers of students who were likely to succeed in them.

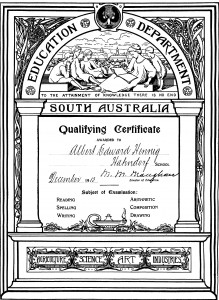

The fomalising of school examinations under the new departments of education or public instruction, South Australia, 1900. From Reg Butler, Lean times and lively days. Adelaide: Investigator Press, 1979.

The earliest government high schools depended a great deal for their reputation on their students’ examination successes. In post-elementary Catholic schools for boys, success in public examinations contributed to the building of a Catholic middle class. Others were less enthusiastic, especially those Catholic schools for girls which defined their mission as the making of refined and accomplished Catholic wives and mothers. Nor were some of the Protestant elite boys’ schools happy with the increasing importance of public examination results. Turning boys into examination swats was contrary to the forms of masculinity they advocated, dependent less on student achievements in chapel, schoolroom and examination hall, than the sports field.

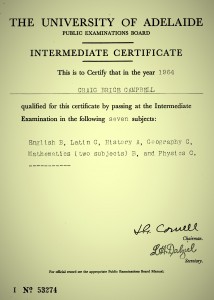

Access to the public/primary school completion certificate, usually named the Merit or Qualifying certificate by the end of the nineteenth century, was not subject to gender discrimination, but the regulations surrounding university matriculation were. The University of Adelaide was the first to allow girls to matriculate, attend lectures and take degrees from the mid-1870s, but other Australian universities were late in allowing this. The University of Adelaide established its first matriculation exam in 1876, the Primary in 1878, Junior in 1882 and Senior in 1887. In those colonies without universities, schools entered their students for examinations in colonies with a university, for example Queensland, the universities of Sydney and Melbourne; and Western Australia, the University of Adelaide.

By the early twentieth century these developments were increasingly challenged. From sources aligned to the New Education came criticism of and occasionally revulsion from the nature and dominance of the different testing regimes. Payment by results was a target, eventually to be modified if not to disappear altogether. New, more practical subjects, such as nature study were introduced to the curriculum in primary schools. State directors of education often sought to reduce the power of the universities over the secondary school curriculum especially as the idea took hold that all young people (increasingly described as adolescents) would benefit from prolonged school attendance.

Several reforms early in the century were meant to address the problems. One was to reduce the power of the universities, their professorial boards, over public examinations. Reformed boards might include men and later women from state education departments and nongovernment schools. Expanding the diversity of representatives on curriculum, assessment and examination boards continued into the twenty-first century. A second initiative was to replace the older examinations and certificates with new ones. In theory at least they would be more responsive to the needs of a broader range of secondary students than that tiny minority who were bound for the universities. Two of the new examinations and certificates were commonly named the Intermediate and Leaving. Later there might be a Leaving Honours. The Leaving Certificate clearly signalled that the completion of a satisfactory secondary school course of study could be an end in itself. Both Intermediate and Leaving certificates provided significant credentials for white collar employment, for several decades beyond the 1920s.

The pressures that built over the early twentieth century had a basic cause. Was secondary schooling to be universal, accessible to all young people, or was it only for the qualified or meritorious few? If it was to be for all, then the dominance of academically oriented public examinations over schooling was a massive hindrance to achieving a universal and useful, prolonged secondary education for all youth.

The universities resisted the changes. In most states, the Leaving became the new matriculation, but not all subjects would be recognised by the universities as being acceptable for matriculation. As a result, the universities retained substantial power over secondary school curricula.

Perhaps more successful in its impact on assessment regimes was the decision by most state governments to establish alternatives to the academic or general (university entrance) secondary courses. At the end of the nineteenth century there had been commercial subjects and qualifications but early in the twentieth there was interest in technical and home economics education, some of the interest arising from the perceived needs of working class youth (this was highly gendered). Where population centres were large enough, separate schools were often established. State branches or departments of technical education developed new forms of assessment and credentials as a result.

Early in this period, the administration of formal, mainly written, examinations was not restricted to universities and state departments of education. In New South Wales for example, there were separately organised examinations that might lead to employment. They included Public Service, Institute of Bankers’, Insurance Company, and Chamber of Commerce examinations. In the long term such examinations retreated in favour of public examinations, though the question of how well school curricula prepared young people for the workforce remained a source of tension into the twenty-first century.

1930s-1970s

Public examination students at work in Queensland, 1940. Source: State Library of Queensland.

In this period criticism of public examinations increased, though except for Queensland, they continued to survive in all states and territories of the Commonwealth. The 1937 travelling conference of the New Education Fellowship was particularly critical. Its publication, Education for Complete Living, devoted three chapters to the issue of public examinations. One of them emphasised how unreliable and lacking in validity their marking was, another, their ‘evil influence’ on school life. The last by the American Isaac Kandel argued that they were about much more than testing student grasp of a curriculum.

Examinations may be used (1) as a means of social control; (2) as a method of educational administration, that is, as a test of the teachers; (3) as a method of admission to schools, professions, public services, etc.; and (4) as a means of instruction, that is, as a method for discovering the progress of pupils and improving instruction. (p. 127.)

For Kandel these four functions had questionable and varying legitimacy. The way forward was to expand the variety of evaluations of student worth and achievements, including ‘pupils’ characteristics and interests, to furnish the basis for educational guidance’ (p. 328). For Beatrice Ensor examinations had few redeeming features. They had to be abolished. They stood in the way of developing an individual student’s ‘infinite possibilities’ (p. 93).

In secondary education the usual way of dealing with an increased recognition of the diversity of student populations, and the aim of increased school retention, was to place students in different schools and courses, apparently responsive to the needs of children as individuals. Gendered expectations had much to do with these placements as did other factors, including ethnicity, ‘race’ and social class. Much of the exercise depended on the use of intelligence testing. Vocational guidance also played a part. A consequence of these developments was to expand the number of assessment practices and credentials available at the end of different courses of study. The continuing problem was that passing public examinations in the academic (general) course generally retained the highest esteem among too many employers.

Students protesting against their failure to make the grade, New South Wales, 1968. Source: State Library of New South Wales.

Examination results were often reported by the press, rewarding the successful (but also exposing the unsuccessful). Rituals were developed, including late night visits to newspaper distribution centres by examination candidates to buy copies of papers in which their results were published. Publication of results might lift school, family and community pride. Swatting, intensive preparation before examinations occurred widely. As rites of passage these practices had their supporters, others argued that they were responsible for injuring the mental and physical health of many young people. Schools announced duxes and brought community leaders into assemblies to distribute prizes for meritorious achievement. Scholarships for future study were also dependent on the results. P.H. Partridge summarised the phenomenon in 1968:

They have achieved a strange popular significance almost as if they defined the meaning or purpose of advanced education; … many Australians have come to imagine that secondary education means to be trained successfully to withstand the ordeal of a series of public examinations and that the quality of a school is to be measured by the number of its examination successes. (Partridge, Society, schools and progress. Oxford: Pergamon, 1968, p. 57.)

Elsewhere the ACER (Australian Council for Educational Research) developed standardised tests for a variety of diagnostic, intelligence discovery, reading-age determination, and other purposes. These were widely used in primary and secondary schools. Their results became important beyond the diagnostic, contributing to the streaming of students into top, middle and bottom secondary school classes. Separate from the usual public examinations and testing as they occurred in schools, this class of tests which were sold to schools by the ACER, were a means of social administration. Early on they were responsive to the eugenics movement, concerned to classify populations as either intelligent and able, or the opposite. Special programs and institutions could be devised for those who were not classified as intelligent and able. Usually the results of this kind of testing supported existing social hierarchies based on ‘race’, social class and English language facility. (See Pavla Miller, Long division. Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 1986, ch. 9.)

The old end-of-primary-school Qualifying Certificate, replaced in South Australia in 1944. Source: Butler, Lean times and lively days.

In the primary schools the pressures arising from testing towards the Qualifying Certificate (QC) and its equivalents decreased. The examinations marking the end of primary school and the issuing of QC certificates came to an end. In South Australia the QC was replaced by a Progress certificate, the granting of which rested on more than the results of formal testing. In Victoria from the 1930s the transition to an appropriate secondary school was managed according to the recommendations of primary school principals alone. In Tasmania, results of intelligence tests were considered along achievement in the end-of-primary scholarship examinations. Scholarship examinations had been used in Queensland and Western Australia to provide eligibility to enrol in a secondary school.

By the 1970s children would routinely advance with their age cohort regardless of achievement. In the 1970s, remedial teaching, and if the school was large enough, remedial classes were established to assist those who failed to keep up with the standard curriculum. Testing of students continued to have the dual function of assessing the grasp of a curriculum, but also sorting and selecting students for different schools, classes and streams.

An Intermediate Certificate, soon to be abolished. South Australia, 1964. Courtesy the author.

The 1970s was a decade of educational reform, a period in which traditional schooling practices came under great criticism, sometimes leading to ‘alternative’, progressive schooling. Assessment regimes, including the continuing power of public examinations in secondary schools, were not exempt from reforms. The movement towards comprehensive secondary schooling had begun a little earlier. In New South Wales the Leaving and Intermediate certificates and examinations were replaced by School Certificate and Higher School Certificate (HSC). In Victoria the dual public system of technical and high schools continued, with their different curricula and testing regimes.

In Queensland, public examinations were abolished in 1970 and 1972 following the Radford Report of 1970. Certificates recording achievement continued to be issued by the state. Responsibility for assuring those who used these credentials that they maintained worth rested with an elaborate moderation process where achievements in the various school subjects across a multitude of schools were compared and if needed, moderated (adjusted).

Each of the Australian states by the late 1970s was experimenting with different forms of testing and credentialling. In some the Leaving Certificate survived for much of the decade. South Australia developed tracks (different courses) for secondary students and a New Matriculation certificate. In several states, school-based assessments were allowed to contribute to the determination of final results. The lack of uniformity and often the limited transferability of credentials across state borders as they arose from different assessment regimes was not unnoticed, becoming a powerful factor in the reforms of the post-1970s period. At the same time there remained continuing pressure from employers and universities for trustworthy standards and credentials. A detailed description of changes in public examinations in each Australian state in this period occurs in Connell, Reshaping Australian education (1993).

1980s-2020s

In this period there were at least three forces that affected the ways that school assessments and credentialling occurred.

(a) High levels of youth unemployment and the subsequent demand for universal secondary school retention through to year 12. This led to a demand for greater inclusivity. One of the principal functions of assessment regimes had been to exclude or fail students who did not meet varying requirements. The new pressure was to include all young people by offering a much broader curriculum with less punishing assessment regimes.

(b) Neoliberalism. This fostered the rise of markets in educational provision. Senior school assessments, controlled by universities and then state boards, were challenged by alternatives. The major alternative, adopted in many nongovernment and occasionally government schools, was the International Baccalaureate. It offered its own curricula and assessment regimes.

(c) The impact of expanding globalisation. This had competitive as well as standardising effects. The OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) for example organised new standards and tests of literacy, numeracy and scientific literacy through the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) following which the member nations were ranked. It became an educational ‘crisis’ if nations were seen to be falling behind the others.

The Blackburn Report (1985) in Victoria addressed the inclusivity issue. A new credential, the Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE) would recognise achievement in a greater number of subjects, including theoretical and activity-based subjects. The report inspired similar developments in South Australia, Tasmania, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Public examinations for many subjects survived. The Queensland example of complete abolition was not followed, although moderation exercises became standard especially in those subjects not dominated by sit-down public examinations.

In the primary and junior secondary schools, high stakes testing diminished. Social promotion, keeping students of specific age cohorts together, replaced the older achievement-based regimes. Opponents, such as the Australian Council for Educational Standards (this organisation’s journal lasted from 1973 to 1988) worried about grade inflation, the collapse of academic standards more generally and the likelihood that disadvantaged students would receive a second-class education as a result.

Globalisation pressures, as well as the old problem of incompatibilities between the curricular, assessment and credentialling regimes of the different Australian states and territories were addressed more vigorously in this period. A national education system with a unified assessment and credentialling system was beyond reach, but meetings of ministers responsible for youth, training and education (the Australian Education Council) began issuing declarations working towards some uniformity. The Hobart Declaration (1989) included a statement of Common and Agreed National Goals for Schooling in Australia.

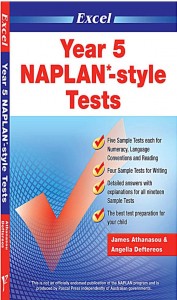

The growth of an industry supporting the anxiety of teachers, schools and parents that they perform well in the NAPLAN tests.

With more impact on the daily lives of students, teachers, schools and school systems was the decision by the Rudd Labor government to introduce standardised testing across Australia: the National Assessment Plan: Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN). This would affect primary and secondary schools alike, generating data that was expected to enable schools to address problems in the literacy and numeracy area. The first NAPLAN report was published in 2008. The effect was to enable school, regional, state and national comparisons. One side-effect was to enable parents who sought educational advantage for their children, to avoid some schools and attempt enrolments in others. The establishment of a My School website made NAPLAN data easily accessible to anyone. There were attempts to control misuse of the data but these were limited in their effectiveness.

The NAPLAN tests occurred in Years 3, 5, 7 and 9. They were conducted by ACARA ,the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (2008- ). The exercise soon encouraged an industry of test preparation exercises and a new set of anxieties felt by students and teachers alike, even though no new credentials were associated with its work.

Conclusion

The ways young people’s educational achievements have been assessed has varied considerably over the last two and a half centuries. The credentials that have been attached to student success have varied also. Australia was relatively late in its introduction of nation-wide standardised testing, mainly for literacy and numeracy. High stakes testing (that is, testing which leads to the opening and closing of future options in higher education and employment) continues to dominate senior secondary education, but a range of subjects and assessment exercises have developed well beyond public examinations, although they retain a place through to the present day in most Australian states and territories.

By the late nineteenth century public examinations had developed whereby students from different schools would compete, usually in written examinations on their understanding of a subject syllabus. By the late twentieth century, public examinations retained a central place, but questions of efficiency and fairness saw reform. Subject syllabuses developed in the direction of detailed statements of aims, objectives, content and outcomes. Not only affecting public examinations, technologies of assessment and measurement developed to decrease subjective judgements, to distinguish between formative and summative assessments, norm-based and criteria-referenced assessments and more. New forms of testing such as the multiple-choice question were developed. The most successful of the teaching machines imagined from the nineteenth century was relatively recent. Modern computers enabled software development that instructed students, but had a great capacity to assess, to provide almost immediate feedback on learning progress.

The top performers in public examinations, the prize winners of Canterbury Boys High School, NSW. 1935. Source: State Library of NSW

Sociological analyses of school success continue to reveal that the children of highly educated middle class parents remained most likely to succeed in most high stakes assessment regimes. Children enrolled in schools with high levels of disadvantage are often at risk. Several scholars have provided important analyses of this phenomenon:

(a) Basil Bernstein argued that working and middle class people had different social usages and frames for language. The language practices of middle class people made them more amenable to the language of schools, made their children more likely to succeed at school.

(b) Pierre Bourdieu argued that educational success was more associated with the habitus, social capital and fields of practice associated with some individuals and social groups (mainly middle class) more than others.

(c) Bob/Raewyn Connell argued that assessment practices were more about ‘gate-keeping’, sorting and selecting young people into courses and work as much as helping them ‘learn’. It was a means of ensuring there was not too much ‘over-supply’ in high status courses or in particular labour markets.

Such negative critiques are only part of the story. Besides ‘excluding’ people, assessment practices have also been a vehicle for helping some young people to enter previously inaccessible territories. For example:

(a) opening public exams to girls in the late nineteenth century ensured that their demand to enter the universities would likely succeed

(b) over the twentieth century, many working class children, by proving their merit in public examinations, were able to receive a higher education and enter the ‘white collar’ and professional workforce

(c) enabling the children of migrant families to enter white collar and professional workforces that had been inaccessible to their parents.

Nevertheless, practices introduced to increase access, decreasing disadvantage, through varying the conduct of public examinations for example, can misfire. In New South Wales where the Higher School Certificate (HSC) continues to dominate senior secondary schooling, applications to alleviate the stresses of public examinations for vulnerable students are overwhelmingly applied for on behalf of students in relatively wealthy nongovernment schools.

Over the centuries, responsibility for testing students has shifted from teacher, school and local authorities to those of centralised authorities established by states and the nation. This causes continual tension. Assessment regimes, their managerial and technical character and their social impacts have significant and variable effects on the lives of young people. Questions about assessment practices are never simple technical questions because assessment and credentialing practices are related to broader social organisation, often advantaging some populations more than others, and in the process, creating new or modifying old social hierarchies. The power of some institutions to influence or control assessment and credentialing regimes may be used to legitimise their place in an educational or labour market, or indeed, to dominate it. (Think of the power of prestigious universities and the value of their degrees.) Such power, influence or control may not necessarily relate to important issues of learning, competence, or even fair access to educational opportunity.