In each of the Australian colonies, usually in the 1870s, there were education acts passed that established public school systems. Their defining characteristics have usually been described as ‘free, compulsory and secular’. The Act that came closest to establishing all three of these conditions at the same time was the Victorian Education Act of 1872. In other colonies and states the conditions that came to be seen as defining Australian systems of public education began as early as 1851 and concluded as late as 1908.

Running the new public school empire. Clerks at head office, Department of Public Instruction, Bridge St, Sydney, 1913. State Library of NSW, GPO 1-16996.

There were other characteristics of the Australian public school systems that were established with these acts of the colonial and state parliaments. One was the establishment of government departments of public instruction or education. Instead of schools being governed by boards and councils of education, the new departments were controlled by government ministers. Other reforms included the abolition of state aid (government funding) to denominational (church) schools. Significant controls by local authorities over the running of local schools were removed. In their place came centralisation. Powerful centralised inspectorates were created to govern the new public school systems.

An important question arising from the ‘free, compulsory and secular’ acts is the degree to which the systems of public education actually did create free, compulsory and secular schooling.

(1) Free

Not all of the 1870s acts established free education. School fees continued in some states into the twentieth century.

(2) Compulsory

None of the 1870s Acts were thorough going in relation to demanding the compulsory attendance of children at schools. Most allowed for substantial periods of non-attendance without penalty, again into the twentieth century.

(3) Secular

Except for Victoria, the colonies allowed some visitation by religious clergy and others to give some denominational/religious instruction. If ‘secular’ meant no Christian influence on the curriculum at all, then none of the new public schools were secular. ‘Common Christianity’ elements survived in some of the textbooks, and often underpinned public school moral education.

Historiography

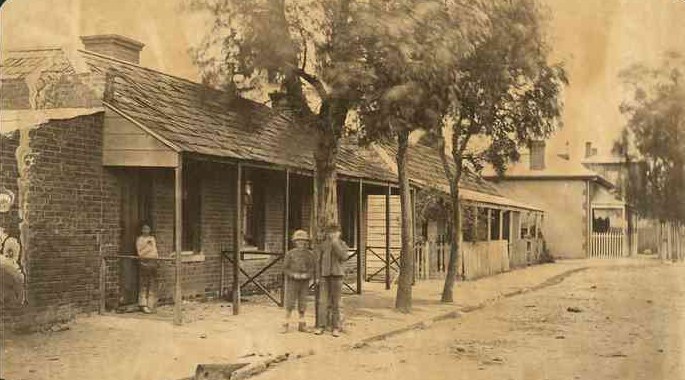

The last few years for state funded denominational schooling, Church of England school at Gulgong, 1870-1875. State Library of NSW, ON-4-Box 3-18320

These acts of the different colonial and state parliaments have been interpreted differently. For some historians they were a culmination, a logical and progressive outcome to decades of inefficient, ineffective and troubled attempts to produce satisfactory schooling in the Australian colonies. The acts could form a satisfying climax to the story of the struggle for universal education. The Whig historiography concentrated on two elements of the story: first, that more schools for more children, separated from the baleful effects of sectarianism, was an excellent outcome, and second, that this outcome was the result of enlightened educational leaders, politicians and others, such as Henry Parkes, George Rusden, William Wilkins, John Hartley, Charles Nicholson and others who resisted the pressures of the unenlightened, and especially Roman Catholic and to a lesser degree, Church of England, leaders.

Children off the streets and into schools, a step forward with compulsory attendance. Children in Bent St, Adelaide, c. 1870. State Library of SA, B 2465

Other historiographical traditions were more critical. They could interpret the acts as the triumph of intrusive central governments over local control, the triumph of state supported Protestantism over Catholics, as the bringing of working class and other children of the ‘unruly’ classes under state paternalism and control, and a means of further oppression for Aboriginal children and families.

The acts play an important part in several intersecting historical and historiographical issues of consequence. They include:

- the history of childhood

- the size, behaviour and supervision of families

- the making of the modern teacher and the school inspectorate

- the systematising of the work of the school (e.g. school timetables and curricula)

- the increasing capacity of the state to organise the population in general

- relationships between governments and churches

- the governing of populations at the margins, such as Indigenous peoples

- new definitions of public and private in Australian society

- urban, suburban and rural development

- the extension of literacy, numeracy, and general education of the population

- child and youth labour-force participation

Analysis by historians of the issues arising from the foundations of public education systems are not exhausted. Most of the points (1)-(11) above continue as significant for contemporary education policy.

Common features of the education acts

This list is developed from the works by Austin and Selleck (1975), Barcan (1980) and Campbell and Proctor (2014).

(1) The establishment of Departments of Education and Public Instruction under ministerial control, and the end of the previous Boards and Councils of Education

- 1872 Victoria

- 1875 South Australia

- 1875 Queensland

- 1880 New South Wales

- 1885 Tasmania

- 1893 Western Australia

(2) Compulsory attendance, usually by children to the age of 13. In brackets is the date when the laws were actually proclaimed or amended to become effective. In most cases the compulsory clauses allowed extended absences.

- 1868 (1916) Tasmania

- 1871 Western Australia

- 1872 Victoria

- 1875 South Australia

- 1880 New South Wales

- 1870 (1900) Queensland

(3) Abolition of school fees for the years of compulsory attendance. They did not always remain abolished, especially for public secondary education

- 1870 Queensland

- 1872 Victoria

- 1892 South Australia

- 1901 Western Australia

- 1906 New South Wales

- 1908 Tasmania

(4) Abolition of state aid, that is the withdrawal of government funding from denominational (church) schools.

- 1851 South Australia

- 1854 Tasmania

- 1873 Victoria

- 1880 Queensland

- 1882 New South Wales

- 1895 Western Australia

(5) Establishment of a mainly secular curriculum in national or public schools, with or without limited compensatory rights for churches to provide some denominational teaching, or non-denominational scriptural reading/instruction

- 1852 South Australia

- 1854 Tasmania

- 1872 Victoria

- 1875 Queensland

- 1880 New South Wales

- 1895 Western Australia

The main Education Acts

This is a list of the main acts of the various colonial and state parliaments by date of passing. Later amendments to the Acts, and the regulations arising, were often important, but they are not listed here. The names of each of these Acts are hyperlinked through to their originals.

- Education Act, 1851, (South Australia)

- Public Schools Act, 1866 (New South Wales)

- Education Act, 1872 (Victoria)

- Education Act, 1875 (South Australia)

- Public Instruction Act, 1880 (New South Wales)

- Education Act, 1885 (Tasmania)

- Elementary Education Act Amendment Act, 1893 (Western Australia)

- State Education Act, 1875, (Queensland)

Significance of the ‘free, compulsory and secular’ education acts

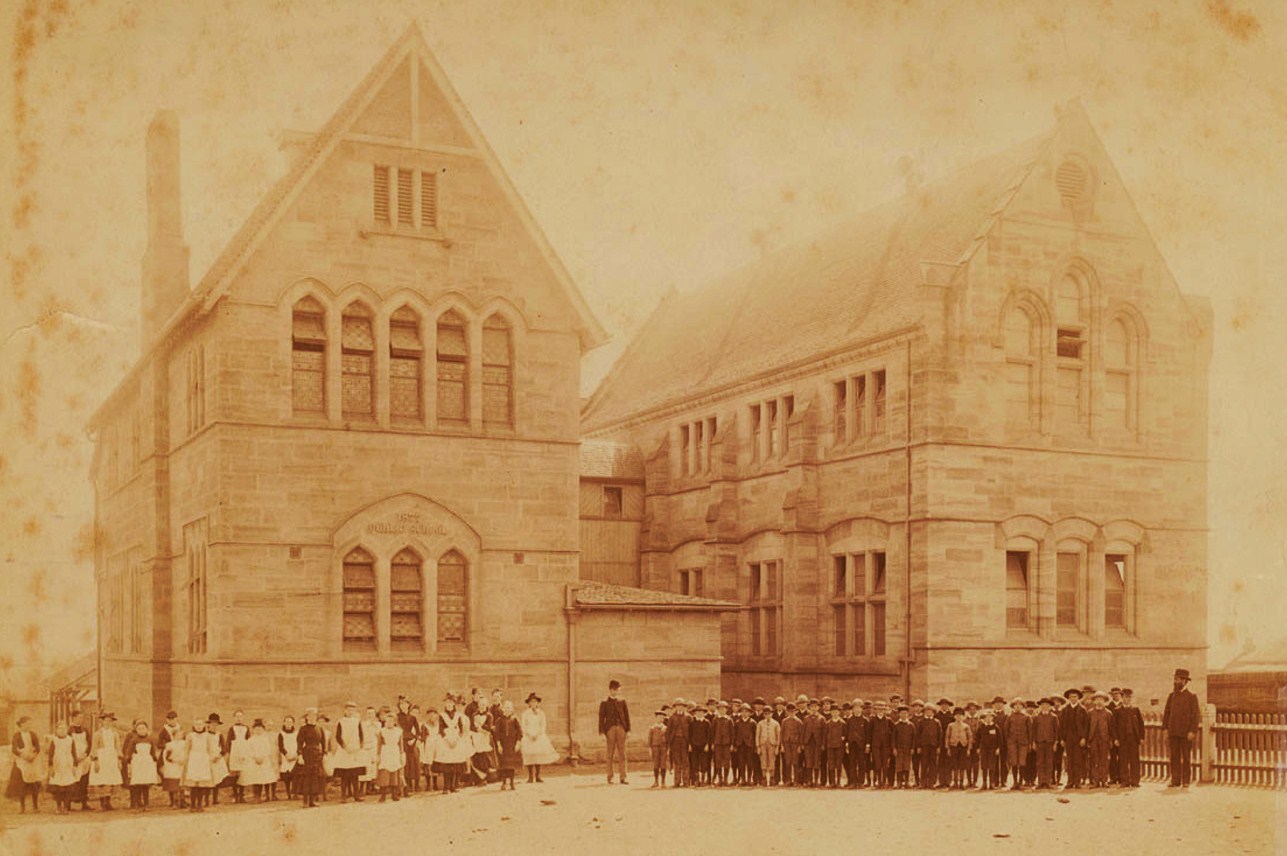

After the Public Instruction Act, Rozelle Public School, New South Wales, 1885. State Library of NSW, SPF-734

Even though the implementation of these acts was not always speedy, and the various conceptions of free, compulsory and secular could be murky, together they constituted the emergence of a modern Australian public school system. They formed an education settlement that sought to go beyond the great controversies over the proper roles of churches and state in education, local community and state, and in curriculum, religious and secular instruction—and the issues that families faced in deciding on school attendance for their children.

In each capital city a Department of Education was established to run the centralised system, led by a Director of Education. Head office in Bridge Street, Sydney, 1915. State Library of NSW, GPO 1-16210

In many ways their significance in Australian public and educational policy developed a clarity not seen at the time of their enactment. For interested persons and parties at the time the struggles, concessions, victories and defeats, sometimes clause by clause as they proceeded through the parliaments were too near. Much later, some public school supporters believed the acts were more pristinely secular than they were in fact. As the Roman Catholic Church in Australia became more oppositional over time to the ‘no state aid to denominational schools’ settlement, the acts contributed to the sectarian bitterness between Catholics and Protestants that divided Australians for much of their late nineteenth and twentieth century history.

From the 1980s, a century later, almost every element of the 1870s acts was challenged. State education departments were decentralising and in many states, public schools had considerable autonomy devolved to them. One way or another public schools and public school systems sought fees of some kind from parents to assist with the tuition of their children. State aid to nongovernment schools, denominational and secular, had been quite restored after the near century of no state aid. The mainly secular curriculum held, although in several states governments allowed the appointment of chaplains from different churches to public schools. Controversies over religious education, its content and teaching, recurred at regular intervals in most states.

The element of the 1870s acts that persevered, and only became stronger over time, was the compulsory clauses concerning school attendance. In the early twenty-first century these often reached through to 17 year old youth, though participation in education and training did not always have to occur specifically in schools. Some children and families continued to resist the compulsory clauses as they had for more than a century. Compulsion and its outcome, the ‘crime’ of truancy for example, was a central issue for the ‘interventions’ by federal governments (2010s) into Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory.