The provision of state aid (government financial assistance) to nongovernment (independent and Roman Catholic) schools has been a major source of debate in Australian education from colonial times. For nearly a century a policy of providing no direct state aid to nongovernment schools was supported by Australian governments at all levels. This changed in the early 1960s when the federal government, under Prime Minister Robert Menzies, provided grants to both government and nongovernment schools to build science facilities. This decision prompted a change in the attitude of both state and federal governments toward state aid and some public funding for nongovernment schools has now become the norm in Australia. As a consequence the state aid debate now tends to be centred on the amount funding that should be provided to nongovernment schools, and which schools deserve the most funding.

Colonial and post-federation national approaches to state aid

For most of the early colonial era schooling in Australia was largely in the hands of church or private enterprise. From the middle of the nineteenth century colonial governments became more involved, but it was not until the last quarter of the century that landmark legislation creating free, compulsory and secular education was passed in most of the colonies. During the same period public funding was withdrawn from nongovernment schools in all the Australian colonies: South Australia (1851), Tasmania (1854), Victoria (1873), Queensland (1880), New South Wales (1882) and Western Australia (1895).

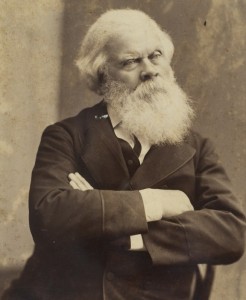

- Figure 1: Henry Parkes in 1887, one of the colonial premiers who engineered the end of state aid to non-public schools. State Library NSW, P1/1302

Following the withdrawal of government funding, Catholic schools continued to operate in all the colonies and there were also some much smaller church efforts (e.g. Lutheran schools), a small number of non-Catholic church-affiliated schools (most offering more than just elementary education), some private schools and a few others such as Jewish schools. This was the state of affairs at the time of federation and no federal government involvement in education was contemplated, given that education was considered a state matter under constitutional arrangements. With a few minor exceptions, things stayed this way until the middle of the twentieth century. The central issue that maintained this arrangement was a strong belief in the division between state and church amongst the Australian community, with deep sectarian differences being evident in virtually every stratum of society. This ensured that public funding for church-affiliated schools was not supported.

Resumption of state aid to non-government schools

The first sign of major change occurred with the coincidence of three developments. The first was the slow but steady breakdown of the sectarian antagonism between Catholics and Protestants. The second was the so-called ‘education crisis’ which was created by population growth following the Second World War (the ‘baby boom’) and by the growing trend for more Australian children to stay longer at school. In response to this crisis increasing pressure was placed on the federal government to provide direct financial aid to both government and nongovernment (particularly Catholic) schools. The third was the split in the Australian Labor Party (ALP) during early stages of the Cold War in the 1950s when anti-communist sentiment was at its strongest in Australia. The emergence of the Catholic-dominated, and staunchly anti-communist, Democratic Labor Party (DLP) as a significant force in Australian politics after the split provided the Liberal-Country Party Coalition with an opportunity to secure a stranglehold on government, particularly at the federal level. As the DLP supported the re-introduction of state aid, the Coalition viewed the adoption of pro-state aid policies as being advantageous to it in winning the Catholic vote. Previously it had been mainly directed to the Labor Party. By winning preferences from the DLP, the Liberal-Country Party Coalition won long-term government through the 1950s and 1960s.

- Figure 2: Prime Minister Robert Menzies whose government granted state aid to non-government schools once more from the mid 1960s. Photographer: Ian Hanna, State Library of Victoria, H90.11/13

The decision of the Menzies Coalition Government to provide grants to both government and nongovernment schools for science facilities, announced in the lead-up to the 1963 federal election, is seen as the breakthrough that ended the no state aid policy that had existed throughout Australia since the late nineteenth century. Initially, aid to nongovernment schools was provided for science laboratories and then school libraries, reflecting priorities that emerged for schools in all sectors in the 1960s. At the end of the decade, a more general scheme of grants was introduced by the federal government. Some of the states had already introduced per capita grants to non-government schools.

The closure of a number of Catholic schools in Goulburn in 1962 in protest at the continuing refusal of state and federal governments to provide any direct assistance to non-government schools had highlighted the plight of Catholic schools.

There was increasing recognition that many of these schools faced an uncertain future as the Catholic teaching profession moved from being drawn mainly from religious orders to a lay workforce requiring wages equivalent to those paid to teachers in other schools. Associated with this was acknowledgement of significant disparities in education provision across the complete spectrum of government and non-government schools.

Resistance to the restoration of state aid

Following the passing of the States Grants (Science Laboratories and Training) Act (1964) and other state aid legislation, a number of groups opposed to state aid contemplated mounting a legal challenge against it. Eventually, the Australian Council for the Defence of Government Schools (commonly known as DOGS) took the matter to the High Court in the early 1970s. Technical difficulties delayed the case but a High Court challenge was commenced in October 1978. The challenge was centred upon section 116 of the Australian Constitution which forbids the Commonwealth from making laws that establish any religion. During the 1970s, a similar ‘no establishment’ rule in the United States constitution had been used successfully in a number of cases opposing the provision of financial aid to denominational schools. DOGS and its supporters hoped for a similar result in Australia. Nevertheless, in February 1981 the High Court ruled against DOGS and in support of state aid legislation.

Legitimating state aid and the Schools Commission

While the Labor Party had contemplated a legal challenge to state aid in the 1960s, its ‘no state aid’ policy had been reversed when Gough Whitlam became federal leader. Whitlam had laid his political career on the line in the late 1960s with his insistence that the ALP embrace the need for public funds to go to at least some nongovernment schools. The social agenda of the federal ALP government which came to power in 1972 under Whitlam’s leadership included a commitment to work toward reducing inequality in Australian society. The provision of additional resources for education was regarded as important in achieving this aim. The Whitlam reform agenda was popular, especially that which supported the belief that school and university qualifications were a key to social mobility and increased life choices and chances for children. The outcome was the Schools in Australia (Karmel) Report of 1973 and the initiatives of the Interim Committee of the Australian Schools Commission, established immediately after the election of the Whitlam Government. It developed the concept of ‘needs-based’ funding for Australian schools. The Australian (later Commonwealth) Schools Commission further developed the policy. For over a decade the federal government received advice from the Commission on the allocation of ‘needs-based’ funding.

The Commission was abolished in the late 1980s. While vestiges of religious sectarianism lingered, it is fair to say that there was broad public acceptance of state aid to nongovernment schools in some form from this period. The debate has shifted to the nature and extent of this support rather than whether such support ought to be given at all. Moreover, as sectarianism has declined the focus of the debate has shifted from ‘church versus state’ to ‘public versus private’. It was not only religious or ‘faith’ schools and school systems that received the new state aid. A range of secular non-government schools did so as well.

The politics of allocating nongovernment school funding

There is now general acceptance of public funding for nongovernment schools on a ‘needs’ basis across the political spectrum and more generally within the Australian community. Consequently, the debate is largely about what constitutes need, how it is measured, and what quantum of funding should be delivered. Determining need and the quantum of support was the focus of much of the debate during late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The federal government’s complex categorisation in the Education Resource Index (ERI) gave way to the Socio-Economic Status (SES) model during the early 2000s when the Coalition held power federally under Prime Minister John Howard. While supporting needs-based funding, the Labor Party has, since the Whitlam years, sought on occasions to eliminate or reduce funding to what are portrayed as ‘wealthy independent schools’. These attempts have been thwarted and some public funding has been provided to all nongovernment schools with those perceived as being the ‘wealthiest’ receiving the lowest level of funding.

It would seem, therefore, that those who argue that all children, and consequently all schools, are entitled to at least some government funding have won the day and that those who argue that ‘wealthy’ nongovernment schools do not need any government funding have been marginalised. This has placed Australia in a somewhat different position to that which exists in United States, where little state aid is provided to non-public schools although that settlement has come under threat in recent times.

The Gonski Report

Following the defeat of the Coalition in the 2007 federal election, the Labor government under Prime Minister Kevin Rudd commissioned a comprehensive review of government funding for all schools. The review committee (chaired by David Gonski) reported in November 2011. It recommended a significant increase in school funding by both federal and state governments and the introduction of a new funding model for all schools.

The new model provided a base amount for each school student (this amount differs for primary and secondary students) with additional loadings to address disadvantage. Its aim, according to the Labor government was to ensure that all schools had the resources they need to provide students with a quality education. In turn, this was tied to the federal government’s National Plan for School Improvement developed during Julia Gillard’s term as prime minister. The Australian Education Act (passed in June 2013) brought the National Plan for Schools and the new funding model into law, although at that time only some of the states had agreed to the plan and it was not clear what effect the new model might have on the level of funding provided to various types of nongovernment schools. While the review committee recommended that the SES model used to determine the level of public funding for non-government schools should in time give way to a new model, in late 2013, any new model was yet to be determined. As was the case when there was a change to the model used for determining the level of funding for non-government schools in the past, the Gillard government indicated that no school will be ‘worse off’ when the new model is introduced.

The defeat of the Labor government at the federal election held in September 2013 left the implementation of the new funding model in the hands of the Coalition.

[Note: In the years following 2013 school funding models by the federal government have had minor variations, but the substantial impact remains much the same, except that with the continuing impact of school choice policies encouraging increases in nongovernment school enrolments, the proportion of federal funding to nongovernment schools increases over time. The perspectives of the Gonski reports have tended to be put aside.]