During the second half of the nineteenth century in England, the cultures of the great public schools were reformed. Even though Thomas Arnold, headmaster of Rugby from 1828 to 1841 gave his name to the reforms, he was only one of a number of school headmasters who influenced the process.

In general the reforms meant schools were more likely to attract wealthier middle class families. The families were often looking for better student supervision and a more serious moral or religious atmosphere. It is likely that without the reforms, the reputation of the great public schools for student rebellions, brutality in their repression, sex scandals and the like would eventually have led to their closure.

By the middle of the nineteenth century a different kind of family life was being taken up by the rising middle class. Companionate relations between husbands and wives, as well as more parental love, time, protection and involvement being invested in children were factors in the change. The sending of children to boarding schools posed a danger. The wildness of such schools was regarded with suspicion as the more engaged supervision, moral and religious seriousness and the closeness of a loving family life would likely be swept aside. The older culture had apparently suited the ‘hunting, shooting, fishing, and drinking’ traditions of the older aristocracy, but it was not for the rising middle class whose wealth and power increased over the century.

By the end of the nineteenth century, schools in England such as Edward Thring’s Uppingham modelled the reforms. Not all schools shared the following reform list equally, but these were the reforms that found their way into boys’ corporate or collegiate schools in the Australian colonies in the late nineteenth century from England. The impact on girls’ and government schools was also significant (see below).

Elements of the reformed culture

Games

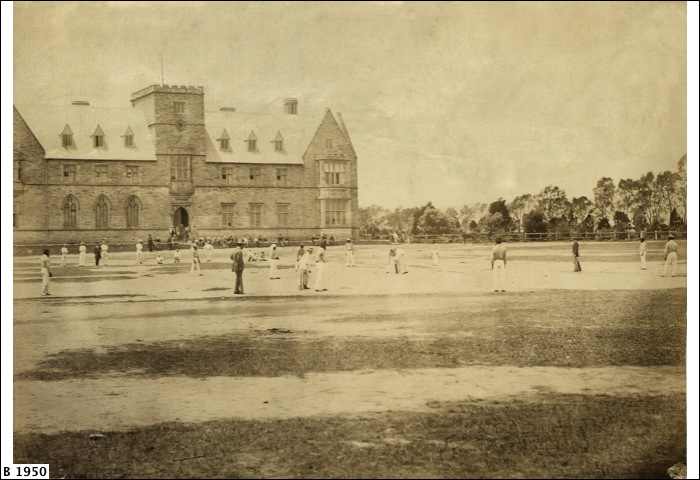

Cricket, the game that bound the Empire together. St Peter’s College, Adelaide, c1872. State Lib SA, B1959

As significant as any of the reforms was the increasing monopolisation of the formerly unfettered free time of boys by organised games. The famous rugby match in Tom Brown’s Schooldays appeared to have few rules, unlimited numbers of boys on each team, no time limits and no umpire to speak of. By the end of the century games were a different matter. In each sport played in the great public schools, codification of rules had occurred. At least as important was the investment of games with the ideal of gentlemanly behaviour. It was good to play by the rules, to be gracious in victory and controlled and ‘manly’ in defeat. The umpire was to be respected. Games could be the perfect training ground for boys who one day might be called upon to govern the Empire dispassionately and fairly. Games often appeared as a solution to a lack of enthusiasm by many boys for their religious instruction or classroom studies. On the sports field there was a moral education to be had, and that education could support a ‘muscular Christianity’. Rugby, cricket and rowing were the essential games. In the southern colonies of Australia, Australian Rules Football replaced rugby. Captainships of sporting teams became opportunities for student leadership, and hero-worship and emulation by younger boys.

Prefects

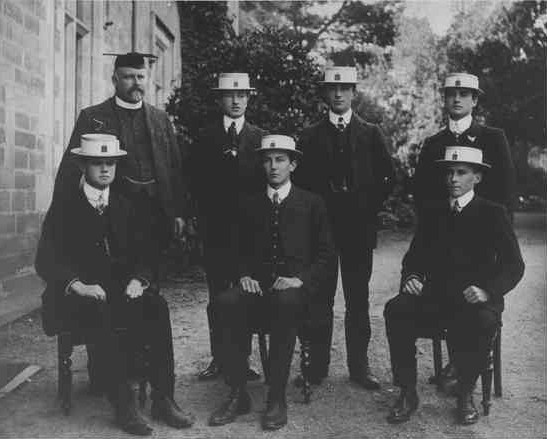

The Headmaster, Rev. Canon Girdlestone with his prefects, St Peter’s College, Adelaide, 1910. State Library of South Australia, B30385

Praeposters and prefects had existed in schools before the mid nineteenth century, but Thomas Arnold tied them more securely to a headmaster’s plan for his school. Prefects were often his students, and his direct agents in governing other students. They were developed as a significant and upright moral authority, usually continuing to have some disciplinary power over students in the schools.

Chapel

Arnold modelled the idea of a more evangelical headmaster/clergyman as leader of a school. The chapel was to become a significant centre of school life, and influence over boys. In Australia the provision of sports fields often took precedence over the development of chapels beyond temporary arrangements.

Uniforms, colours and mottoes

These usually developed later in the nineteenth century. They were part of the corporate culture of a school, where everyone not only belonged, but were ‘seen’ to belong as a result of distinctive clothing and school colours. The dressing of boys and schools in such a way assisted the new demands for supervision and surveillance. The school motto, usually in Latin, attempted to express pithily the social purpose of the school. (For example, St Peter’s College in Adelaide: Pro Deo et Patria, ‘For God and Country’.)

Houses

Junior boys of Manifold House, Geelong Grammar School, 1915. State Library of Victoria.

From their origins as semi-private boarding houses owned or operated by some of the school masters or others, houses were incorporated into the school itself. There students could be better supervised, and organised for a number of useful purposes that included intramural school games as well as some level of pastoral care. The engagement of boys in loyalties to house and school was regarded as having useful moral and character building effects. House responsibilities and events reduced the amount of unsupervised free time that was increasingly regarded as dangerous to boys and the expectations of their parents.

Literary and debating societies, and school magazines

Literary and debating societies developed, engaging boys in cultural activity not totally dominated by schoolroom or classroom, chapel and sports field. They often occupied boys who were less interested in, or not good at games. School magazines had significant corporate purposes beyond the school and its immediate community. Very often they tracked the war service, careers, marriages and so on, of old scholars. They could keep old scholars engaged with the school in the hope of their children’s enrolments, and the possibility of monetary and other gifts to the school.

Old scholar associations

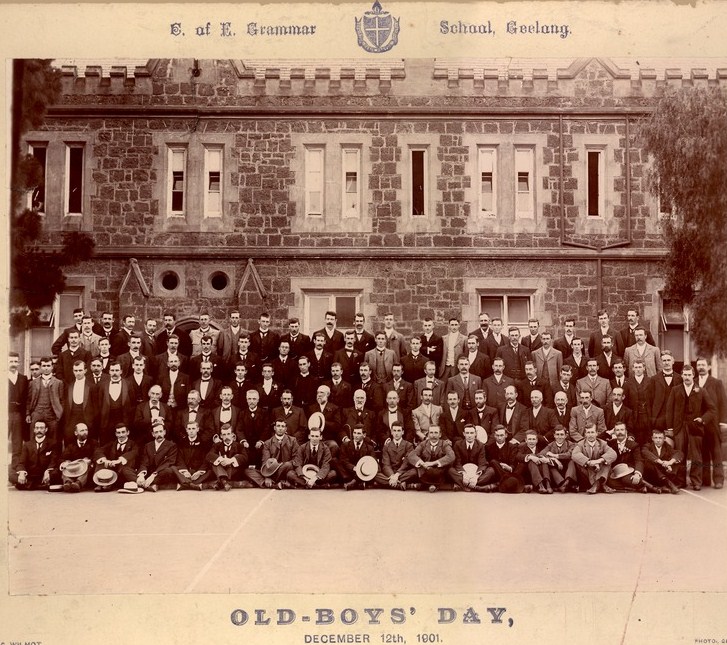

Old scholars and their associations were a vital part of the corporate culture of schools founded on the Arnoldian cultural model. An old boys reunion at Geelong Grammar, 1901. State Library of Victoria.

These developed not only as a means of continuing the friendships developed at school. They provided vital networks that may have affected business opportunities and employment. As was the case with the school magazines, they could keep old scholars engaged with the school in the hope of their children’s enrolments and successful fund-raising campaigns.

Cadets

Cadet corps were often established in the lead up to the Great War. In England some of the greater public schools had significant roles in the provision of officers to the armed services. In New South Wales, The Kings School (Parramatta) adopted military dress as the school uniform. Cadets became an enduring feature of many boys’ schools.

Assembly halls

In England these were often the chapels, but whether multi-use chapels or dedicated assembly halls these were required for the gathering of the whole school as a visible and sentient corporate body. Music, including school hymns and songs were significant, as were arcane rituals specific to individual schools. The walls proclaimed the school’s living history, usually displaying portraits of previous headmasters and boards listing head prefects, sports captains, duxes and the names of the old scholar war dead. These spaces often developed a semi-sacred aura.

School governance

The headmaster of the school in this culture expected to be the principal authority within the school. School trustees and council members were expected to defer to his authority. This did not always occur.

Curriculum

Thomas Arnold continued to place the classical languages at the heart of the Rugby school curriculum, but even though Latin and Greek survived in the English greater public schools, they were of lesser significance in the Australian corporate schools. Modern, English subjects that were commercially useful had been important in high status colonial schools well before the 1870s. (See for example, the description of the curriculum at The Australian College in this dictionary.) At the same time, ‘academic’ subjects were central to school status, whether the subjects were classical or modern/English.

Exclusion and inclusion

In the shaping of school communities there was limited tolerance for behaviour that opposed the school culture. It was not simply a question of challenges to school authority or perceived breaches of the school’s moral or disciplinary codes. A school’s reputation, and therefore future enrolments could be harmed by scandal or other problems. The right to include and enrol, and to exclude or expel were crucial powers of the headmasters of such schools. The Arnoldian culture did not admit open or free access to this kind of schooling.

Buildings

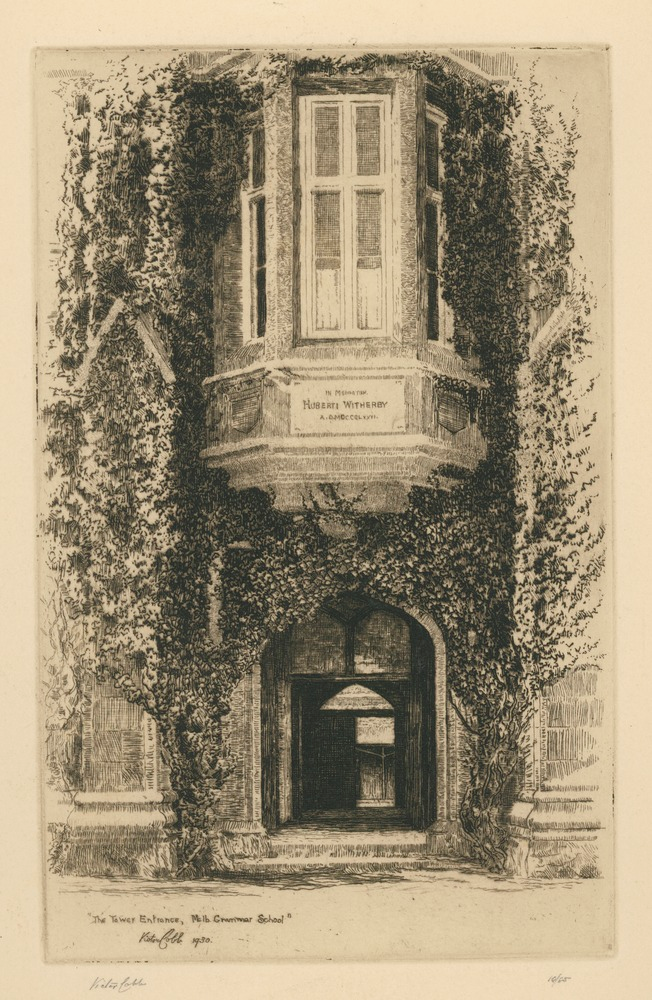

Drawing, Melbourne Grammar School, 1932. Artist: Victor E. Cobb. State Library of Victoria.

To signify the status and distinction of the culture, schools generally occupied or built neo-gothic or architecturally ‘traditional’ buildings that looked both old and substantial. They were thought to add dignity to the culture and activities of the school. They could also produce awe in newcomers and visitors. The Arnoldian culture seemed best suited in spaces or environments that suggested long lasting tradition, even if as a set of practices, they were distinctly nineteenth century, and in that sense, modern.

Manliness, character, the gentleman and elite formation

Many of the preceding elements are connected to a dominant and constructed concept of acceptable masculinity. Despite the reputation of many of the all-boys’ boarding schools for ‘outbreaks’ of homosexual relations between older and younger boys, the most desirable form of masculinity was certainly heterosexual. Good character was associated with courage on the sports field, truthfulness, respect for elders, chivalry towards women, good manners and loyalty to fellow students, school and country. These elements constituted an ideology of manly character that stood in contrast to the inferior masculinities that apparently characterised the dissolute aristocracy, the feckless working class and untrustworthy natives, not to mention fragile women in need of guidance and protection. It was a masculinity that enabled boys emerging from such schools to imagine themselves not only as superior to those not sharing in such schooling, but as natural leaders in the wider society. In the Australian context this form of masculinity has been the subject of significant studies by McCalman (1993) and Crotty (2001). The emergence of this idealised masculinity was often contradicted by outbreaks of bullying, misogyny and bastardisation (initiation ceremonies involving brutality).

Significance of the culture

More broadly, Arnoldian ‘public’ school culture incorporated the idea that it assisted the education and training of men who would be leaders of the nation and Empire into the future. In that sense they had a truly ‘public’ purpose. In England there was usually a strong flow of boys from such schools to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, the civil service and the armed forces. In Australia the links with the newly founded universities and emerging public service were slower to develop. Often the Australian collegiate schools performed a more private function of consolidating those parts of the middle and ruling classes that depended for their wealth on land ownership, larger commercial enterprise and employment in the old professions.

The arrival of Arnoldianism in the Australian colonies

Sherington, Petersen and Brice (1987) credit the significant advent of the Arnoldian culture in Australian church and collegiate schools with the appointments of certain headmasters and masters in specific schools. This is their list of the earliest significant founders:

- Edward Morris in Melbourne Grammar School, from 1875

- Henry Andrews in Wesley College, Melbourne, from 1876

- Edwin Bean in Geelong Grammar and then Sydney Grammar School, from 1874

- James Cuthbertson in Geelong Grammar, from 1875

Melbourne, Geelong and Sydney were the cities where the earliest schools to develop the institutions and cultures of Arnoldianism were found.

Adaptations of the Arnoldian culture were required in the Australian colonies and states. Unlike the English schools, it was rare for an Australian collegiate school to be composed solely of boarders. Day scholars were required to keep the schools financially viable. That meant that unlike in England, the schools were rather more associated with a region than the nation as a whole. Day students also led to compromise in the role that houses and games might play. Evenings and weekends were less available for school activities as school and families competed for the time of the day students. The Australian schools were less likely to be ‘total’ institutions.

At Geelong Grammar School, various elements of the adapted Arnoldian culture were established from the mid 1870s. The events recorded here point to the important relationship of schools such as these with the nation and the wars in which it engaged.

- 1874 School boat club founded

- 1875 Annual GGS Journal founded (school magazine)

- 1875 Number of boarders exceeds day students

- 1878 Geelong Grammar wins the Head of the River competition

- 1883 Albert Garrard joins staff, soon founding the cadet corps

- 1900 Old Geelong Grammarians formed

- 1914 Perry, Manifold, Cuthbertson and Junior houses established

- 1915 Memorial service for old scholars who had died in the war held in the school’s chapel

- 1916 Acorns from Gallipoli planted near the school chapel

- 1922 War memorial cloisters installed in the school

- 1927 War memorial bronze sculpture unveiled by the Governor General of Australia …

Most of the schools incorporating Arnoldian practices were denominational. This is the Anglican, St Peter’s College Chapel in 1933. State Library of South Australia, B8677

A second way that Australian versions of the Arnoldian culture developed differently resulted from the religious or denominational diversity of the colonies. Where the greater public schools were mainly Church of England in the home country, and were therefore closely connected to established national institutions including the universities, in the Australian colonies similar schools were provided by dissenting as well as Anglican denominations. Wesleyan (Methodist) schools were early adopters. Even Roman Catholic collegiate schools run by Marist brothers, such as St Joseph’s in Sydney adopted many elements of the culture. Especially in Queensland and Sydney there were state founded grammar schools that were not denominationally associated at all. As secular collegiate schools, they also adopted and adapted the Arnoldian culture. By the early twentieth century new nongovernment grammar and collegiate school foundations incorporated many elements of the Arnoldian culture from their very beginning.

Girls schools

Middle and ruling class girls schools founded by churches had different priorities. Many kept a role for the female accomplishments curriculum, sometimes as ‘extras’ that were paid for on top of school fees. The culture that specifically supported manly character and leadership in families, business, professions, the armed forces and nation was considered inappropriate for girls’, or ladies’ schools for some time to come, some of it waiting for second-wave feminism in the 1970s.

The role of games in a school culture was problematic for early girls’ schools. It took a decade or two into the twentieth century before vigorous movement, clothing that did not restrict girls’ bodies, and indeed, the ‘sporting body’ itself, were les controversially possible for the ‘feminine’ and the female body. Nevertheless, hats and gloves continued for a very long time.

At the same time some elements of the Arnoldian culture, such as school magazines, uniforms, colours and mottoes, and old scholars’ associations, were quickly taken up in girls’ schools. Prefects arrived a little later than the 1870s. In the early twentieth century pressure grew for the development of girls’ sports. The transition from mainly intramural activity to interschool competition depended on enthusiasts across different schools and their systems.

Government high schools

Government high schools developed from the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, usually with a meritocratic culture as the dominant culture. Passing public examinations and gaining useful credentials for further education and the making of careers were usually more significant than the character-making culture of the corporate or collegiate schools. Even so, elements of the culture were incorporated into the early government high schools. These schools, almost always day schools, meant that house systems for example were limited in scope. Nevertheless, prefects and the development of sports and interschool sporting competitions were pursued. Some of the original and oldest government high schools found their way into the increasingly exclusive sporting associations that governed intercollegiate sport. Adelaide High School, for example, was accepted into the intercollegiate Henley-on-Torrens rowing competition in about 1910, within two years of its founding. As was appropriate for the late nineteenth century Maitland Girls High School, a government school, its motto was Labor Omnia Vincit (‘Work Conquers All’). Newcastle Girls High sought escape from its meritocratic purpose with Remis Velisque (‘With Oars and Sails’).

The social significance and development of Arnoldianism in Australia

Arnoldianism provided corporate schools seeking to educate youth of the wealthier middle and ruling classes with a distinctive set of practices that enabled them to insist that their schools and their students were superior to other schools and their students. Arnoldianism was a significant contribution to the role that schools played in social class formation and relations in Australia.

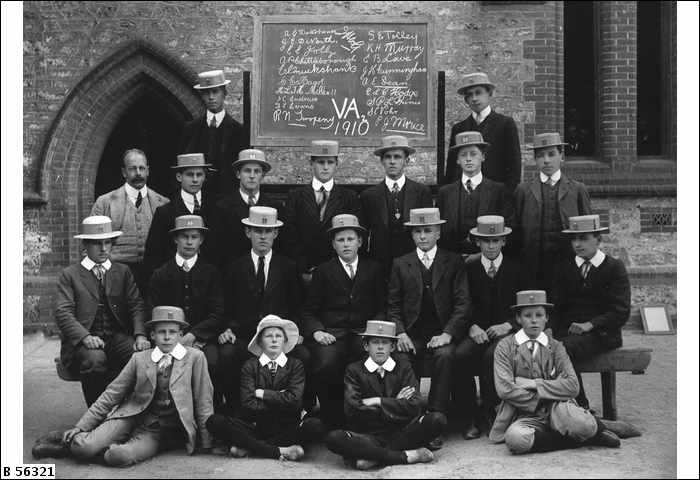

A group of teachers and students at St Peter’s College, Adelaide, 1910. Distinctive uniforms for students are well on their way. State Library of South Australia, B56321

The Arnoldian culture was privately useful to families in the process of upward social mobility. The schools involved provided desirable forms of respectability, and connections to significant networks of political power, commercial activity and more. These schools and their culture helped consolidate social classes in the colonies and states of Australia where the social structure was less stable than in Britain.

The games culture assisted the rise of organised sport in Australia, but one of the problems that occurred as a result of its pervasive influence, was that of ‘athleticism’. In some schools, the demand for sporting success overwhelmed other elements of the school. Under these circumstances, boys who were either not good at or were uninterested in sport could suffer. So could the activities of the schoolroom and chapel. With athleticism there was no school hero but the sporting hero.

The dominant model of masculinity left little room for other forms of masculinity. Bullying and other forms of aggression could result. In more recent times, these dominant forms of masculinity in the older corporate or collegiate schools have often been seen as an impediment to boys’ success in the school room as pressure has grown for public examination success in all schools.

Arnoldianism contributed historically to the reigning in of youth freedom and relative autonomy. Before the reform of the public schools, youth in such schools had considerably more control over their time and activities. The control and discipline exerted by school authorities were spasmodic and more arbitrary in nature. Arnoldianism is a factor in the long term history of youth, and more specifically in the emergence of the modern male adolescent.

In the period following the late 1970s, as neoliberalism has reshaped not only the economy but many social institutions including schools, the Arnoldian culture has come under considerable pressure:

- headmasters and headmistresses have tended to withdraw from the role of moral leadership in their schools as they increasingly resemble CEOs (Chief Executive Officers) in business corporations

- as a market in schools has developed, schools are increasingly seen as competing for customers—and offering a product superior to that offered by others, whether that be better student results or superior plant. In the process, Arnoldian practices and institutions tend to become saleable commodities rather than a school culture inspiring loyalty across the generations.

Deriving from a reformed set of school practices designed to correct the problems of public schools of eighteenth and early nineteenth century England, Arnoldian school culture in Australia has adapted to changing social circumstances. Even in its most recent forms as neoliberal inspired school markets occur, it remains capable of providing distinction and confidence to many of the youth who experience it. It retains a role in social class formation and consolidation. Others of course, have always found its operation oppressive, sexist and undemocratic.