Schools do not exist for the sole purpose of educating young people in the knowledge and skills that are mainly agreed as essential for employment, citizenship and social life in general. They are also about inculcating belief systems that may be more or less explicit, closed or open to critical challenge. Organised religions in Australia have commonly regarded schooling as an essential part of maintaining and fostering the belief systems that give their communities solidarity and coherence.

A crucial question for the religious organisations that manage their own schools has been how to secure and maintain a workforce of teachers who uphold the culture and teachings that they consider fundamental to their beliefs. In Australia, this has been a matter of concern for these organisations since the beginning of British colonial settlement. It has resulted in regular determinations concerning the moral, behavioural and religious characteristics required of teachers. In the early days of the colony of New South Wales, the chaplains of the Church of England who had responsibility for providing or supporting schools commonly complained that they had to tolerate teachers who were less than satisfactory.

For the colonial chaplains, undesirable teachers might be dissenters (such as Wesleyans) or convicts or emancipists, or those who performed their duties poorly, regardless of their religious affiliations. A common charge was that schoolteachers were too often drunkards. Why were such teachers supported by early colonial governments? The principal reason was that persons who might be considered suitable to teach were in short supply.

The tension between control over what kind of person is employed as a teacher, and the availability of teachers has a long history. One example dates from as late as the 1960s. From the 1870s, married women were usually barred from permanent employment in public education systems (discrimination on the grounds of marital status), but with the post-World War II baby boom, their labour became essential in the staffing of schools. This brought an end to the privileging of unmarried women for teacher employment that had lasted from the 1870s to the 1970s.

From the 1840s, National, non-denominational, then public schools in each colony, and then states after 1901, may not have had religious tests for the employment of teachers, but they certainly had regulations that demanded respectability, good character and obedience to their employers. Such regulations survive into the early twenty-first century. New South Wales, for example, regulated against the employment of teachers exhibiting ‘disgraceful, improper or unbecoming conduct’. For privately owned schools in the nineteenth century there were no formal regulations, but a fall from grace in these terms might result in the threatened or actual closure of schools.

When public school systems were founded from the 1870s, their inspectors and directors were well aware of the threat to both the legitimacy and expansion of the systems if teachers were not closely managed in this regard. A range of sanctions for offences might include formal censure, transfer to a less desirable school, demotion, or dismissal.

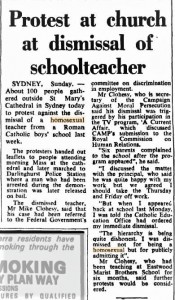

One of many cases. Canberra Times, 20 October1975

In the nineteenth century, Education Department inspectors were almost always male, with teachers increasingly female. The common assumption was that women teachers would be moral guardians of girls, and if unmarried. they would be chaste. Catholic schools, as the largest of the non-public school systems, regulated for the sexuality and sexual behaviour of teachers. Religious teachers (nuns and brothers) were required to be chaste by vow. As they were increasingly replaced by lay teachers through the second half of the twentieth century, such teachers, especially the unmarried women, were also expected to be chaste and faithful to church teachings. Marriage was the sole acceptable venue for the expression of active female sexuality. The gendered discrimination that women experienced under these arrangements has been well documented. What constitutes acceptable behaviour, morality and character changes over time. In the late twentieth century, a major challenge was launched against many prescriptions that had been in force since the previous century. These challenges arose from the combined effects of reinvigorated feminism, the sexual revolution and New Left challenges to the prevailing structures and practices of gendered institutional and state power. On the whole, religious organisations resisted these changes, none more so than the Catholic church.

Teacher unions responded to these challenges in a variety of ways. During the 1970s, they began to advocate for the dismantling of the more authoritarian and gender-discriminatory relations, practices and regulations employers exercised over teachers. In some cases, smaller progressive and independent schools took the lead, as did some state departments of education, for example in Victoria (unlike in Queensland), through their anti-discrimination policies and units.

The issue of teachers’ sexual identity and behaviour

The issue of teachers’ sexual identity and behaviour

Same-sex attracted men and women have always worked as teachers in public, private and other nongovernment schools. It was usual for these men and women to be highly discreet, hidden from view, especially when homosexuality was illegal. Exposure might lead to dismissal, and in some cases, imprisonment. From the 1970s, as a result of changes in attitudes to sexual orientation, and the public demands of gay and lesbian lobby groups for equal, non-discriminatory treatment, many employers of teachers either chose, or were forced, to change their policies and practices.

Nevertheless, there were different degrees of toleration by employers for same sex attracted teachers in schools and school systems for a wide range of reasons.

In Victoria, one challenge to government and the Education Department arose from the publication of the Young, Gay and Proud booklet in 1978. While addressing gay and lesbian youth, this booklet also raised questions about the working lives of teachers. School principals were instructed by government that such publications were unsuitable for school libraries. Nevertheless, in several states, gay teacher and student groups began to agitate for change.

In Queensland, a trainee student teacher, Greg Weir, came to prominence as a spokesperson for a gay student support group. When Weir completed his training at the Kelvin Grove College of Advanced Education in 1976, the Queensland government refused to employ him. The Minister for Education said in parliament that ‘student teachers who participated in homosexual and lesbian groups should not assume they would be employed by the Education Department on graduation’. A substantial campaign concerning the rights of gay and lesbian student teachers and teachers ensued. The Queensland government under Premier Joh Bjelke Petersen (1968-1987) was socially and educationally conservative and refused to give way.

Anti-discrimination legislation, teachers and teacher employment

All the laws and regulations affecting the employment of same-sex attracted teachers over time cannot be detailed in this entry. Generally, stronger protections for teachers have developed in systems of public education. Teachers employed in nongovernment schools and systems have fewer protections, despite a common expectation that public funding of nongovernment schools should mean that these schools are bound by anti-discrimination legislation. Many churches, including the two most powerful, Anglican and Roman Catholic, were vigorous and successful in pursuing the right to discriminate against the employment of same-sex attracted teachers.

All the laws and regulations affecting the employment of same-sex attracted teachers over time cannot be detailed in this entry. Generally, stronger protections for teachers have developed in systems of public education. Teachers employed in nongovernment schools and systems have fewer protections, despite a common expectation that public funding of nongovernment schools should mean that these schools are bound by anti-discrimination legislation. Many churches, including the two most powerful, Anglican and Roman Catholic, were vigorous and successful in pursuing the right to discriminate against the employment of same-sex attracted teachers.

Regardless of the exemptions to anti-discrimination legislation won by religious organisations and church-owned schools, large numbers of same sex-attracted teachers continue to be employed in their schools. Many of these teachers avoid submitting themselves to hostile comment or discrimination when it comes to promotion or continuing employment by keeping their non-school lives as private as possible. As a protective strategy this separation of the professional and the private is difficult to maintain. Exposure places teaching careers at the mercy of the often unpredictable attitudes (from acceptance or tolerance through to intolerance) of managers, employers and, occasionally, groups of parents.

Complicating factors

The apparently straightforward issue of equal rights for heterosexual and non-heterosexual teachers as they are employed in schools, is complicated by related issues.

(1) Paedophilia

One of the moral panics that regularly emerges in schools concerns paedophilia. As the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Final Report, 2017) decisively revealed, paedophile teachers may operate in public and non-government schools, although according to the Commission, many of the worst examples have occurred in church-owned nongovernment schools. Many of the offenders were men who were known by their managers to be paedophiles and who were allowed to operate in schools for years.

The vast majority of same-sex oriented teachers are not paedophiles, but the moral panics arising since the activism of the 1970s, and more recently following reactions to the Royal Commission, have often made life difficult for them. The fact that most paedophiles, convicted or not, have been heterosexual in orientation, and that they most commonly operate within their own homes and families rather than schools, tends to be overlooked.

There is evidence that one effect of the moral panics around paedophilia has been to dissuade men from entering the teaching profession, especially in the pre-school and primary years.

The case of a Victorian teacher, Alison Thorne, who in 1983 defended the right of a group of teachers to advocate for a reduction in the age of consent provides an early example of media-led moral panic. Thorne, despite considerable union, legal and other support, was removed from her teaching position after her actions were reported in the press.

The confusion between paedophile teachers and lesbian and gay male teachers causes difficulties for gay and lesbian teachers in schools. Sometimes this confusion is deliberately promoted as a means of opposing equal employment rights.

Cover of Quarterly Essay magazine, 2017

(2) Homophobia

Attempts by schools and systems to develop and implement sex education policies and curricula that address homophobic bullying and the youth suicide that often arises from it, also complicate the lives of same-sex attracted teachers.

Effective sex education for school youth has long been controversial. Especially since the 1970s, the inclusion of resources for informed teaching about the broad range of human sexual activity has often caused pressure and panic in various conservative constituencies.

In 2010, a program was introduced in Australia to provide training, resources and assistance for the establishment of school and community environments that were physically and emotionally safe, well-disciplined, and conducive to learning. Known as the Safe Schools Program, it was associated with a Safe Schools Coalition, an Australian national network of organisations working with school communities to create safer and more inclusive environments for same sex attracted, intersex and gender diverse students, staff, and families.

The inclusion of teachers and other school staff in the program was a response to evidence that lesbian, gay male and other sexual orientation minorities were often abused in schools by students, and sometimes fellow staff, in addition to the other long-standing threats to their well-being and employment.

The implementation of the Safe Schools Program became extremely difficult in many jurisdictions after various lobbies, conservative and Christian, mounted a vigorous campaign of resistance to it. State governments found it difficult to resist the pressures. The persistence of traditional teachings about sexuality and sexual expression by the Catholic Church in particular made its opposition predictable.

Complicating issues such these, and their associated moral panics, have had the effect of making it politically difficult to include teachers in anti-discrimination legislation protecting the human rights and employment of non-heterosexual teachers.

From a demonstration for gay rights in the 1970s.Photo: Sydney Star Observer, 2014

Haysell (Hazel) Tennant

In 2018, Paul Murphy, a Sydney lawyer who specialised in employment law, brought to public attention a mid-1970s case of discrimination against a practising teacher known as the Haysell Tennant case. Murphy argued that it was relevant to the debate that had been sparked by a proposed federal government bill that was intended to legislate for ‘religious freedom’. Included in the proposed bill was a confirmation and consolidation of the right of nongovernment church-owned and managed schools to discriminate against teachers based on their sexual orientation.

In the mid-1970s, Haysell Tennant was a primary school teacher of ten years standing at St Aloysius’ College, a Roman Catholic independent primary and secondary day school for boys, located in Kirribilli, on Sydney’s lower north shore. She had been a novitiate in the Sisters of Mercy, but did not complete her training. When looking for work, it seemed sensible that she should teach in the system that she knew, in a Catholic school. She was dismissed in 1975 by the school’s headmaster, Gregory Jordan SJ. Haysell Tennant had taught successfully in the school for a decade. The headmaster gave no reason for her dismissal. Her contract stated that all that was required for dismissal was the giving of due notice.

In this case, the Independent Teachers Association (union) appealed the decision on behalf of its member, Haysell Tennant. The case was brought before the then Industrial and Arbitration Commission of New South Wales in 1975. A full court overruled the termination, and reinstated Tennant at St Aloysius’ College. The court held that the failure to give reasons for the termination was unfair, and that alone was considered sufficient grounds for overturning the dismissal.

Many years later, The Fair Work Act (Commonwealth, 2009) addressed issues concerning unfair dismissal. It became legally necessary both to provide valid reasons for a dismissal and to communicate the reasons to the employee.

According to Murphy, the St Aloysius school leadership believed that Haysell Tennant was a lesbian, an allegation not made to her personally. She believed that her private life, her sexual orientation, was her business, not that of the school. ‘After the reinstatement of Tennant, the school directed her to perform duties away from the classroom and to minimise or have no contact with students and parents. She was “sent to Coventry”‘ (Murphy, 2018).

Some months after enduring this treatment Haysell Tennant took her own life.

Significance of the Haysell Tennant case

This particular case is significant in a number of ways. First, it represented a successful challenge to teacher dismissals that gave no reason for the decision to terminate a teacher’s employment. Second, it exposed the vulnerability of lesbian and gay male teachers, no matter how accomplished they were as teachers, to discrimination to the point of dismissal in schools. Third, it established a precedent that the Independent Teachers Association should fight such cases on behalf of its members. (The unions of nongovernment schoolteachers were often more sympathetic to the actions of employers than those of public school teachers.) And fourth, it signalled to church-owned nongovernment schools that they had to manage their teacher employees with more respect.

The Haysell Tennant case also signalled to the managers and owners of church schools that they needed to be more determined in ensuring that future legislation, especially that concerned with anti-discrimination in the area of employment, specifically exempted them from having to treat the employment of teachers with non-heterosexual identities and orientations in a fair and non-discriminatory manner. The decision by the Liberal-National Party federal government in 2019 to confirm such exemptions in a proposed bill concerning religious freedom reflected the success of this determination. (See note below.)

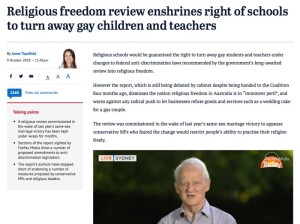

Preparing a federal bill for religious freedom. From Sight Magazine, 9 October 2018.

Conclusion

In Australia and internationally there has been considerable research into the experience of gay and lesbian teachers in schools.

Litton (2001) presented the stories of gay and lesbian Catholic elementary school teachers in the United States. These teachers shared their fears and hopes, and the strategies they used to survive while working in Catholic elementary schools. They seemed to accept the oppression, and chose to work within the system, attempting to create a more inclusive school environment that echoed the gospel message of love for one another. Nevertheless, these teachers acknowledged that they experienced a conflict between their religion and their sexual identity. They did not feel able to come out to their students, though they acknowledged there would be benefits in doing so. They believed that they had to work harder than their heterosexual colleagues so it would be difficult for school administrations to dismiss them. Research in Australia suggests these American conclusions are relevant to Australian teachers in similar schools.

A later study conducted among Victorian GLBT (gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender) teachers revealed that improvements in the status and protections available to such teachers were little known in comparison with the protections for students. Many teachers in government schools were open about their sexuality with some staff members but fewer had come out to students. Teachers in religious schools had more difficulties, causing some to leave the sector (Jones, Gray & Harris, 2013).

Ferfolia (2005) examined the ways in which some religious schools in New South Wales maintained and perpetuated discrimination in relation to lesbian teachers and lesbian sexualities. These strategies included threats of dismissal, forced resignations, implicit harassment, monitoring and surveillance, curriculum silences, and censorship. In silencing lesbian sexualities, the schools influenced teachers’ daily operations and limited their freedom of speech. State-wide anti-discrimination legislation, which exempted some private institutions from compliance in the area of sexuality, reinforced discriminatory practices, and ultimately silenced protest against violence perpetuated against many of the participants in Ferfolia’s research.

Downey (2001) recorded problems for teachers in rural Australia, not only arising from homophobia, but the popular (but mistaken) assumption in many rural communities that ‘gays’ were also likely to be paedophiles.

Sutherland (2017) recorded the events of the particularly difficult year for same-sex attracted teachers when the Safe Schools Program was ferociously attacked in 2016 by conservative politicians, media, and right-wing Christian lobbies. Sutherland argued that ‘the anti-Safe Schools campaign was a litmus test for the Australian Christian right–and it proved the right’s power to influence and shape public discourse. But it also revealed the invisible labour of those who work to keep schools safe. Many of the people implementing the program are themselves part of the LGBTIQ community, and their vulnerability to excessive stress has never been more apparent.’ Sutherland also referred favourably on the work of the public teachers’ union, the Australian Education Union, in defending the program and affected teachers.

The problems faced by same-sex attracted teachers in schools are both historical and on-going.

The exemptions to anti-discrimination legislation enjoyed by nongovernment schools appear relatively well defined, in contrast to the conditions for dismissing or disciplining teachers more generally. Relevant legislation and regulations can be found in both federal and state government jurisdictions. In New South Wales for example, two Acts of relevance are the Teacher Accreditation Act (2004) and Child Protection (Working with Children) Act (2004). Neither specifically address the issue of teachers’ sexual orientations or identities. The emphasis is on professional conduct and the protection of children.

The experience and tragedy of the working life of Haysell Tennant as a teacher in a Catholic school in the 1960s and 70s remains highly relevant for lesbian and gay male teachers in the early twenty-first century in all schools, but especially in religious schools.

Note

(1) Since the election in 2022 of the federal Labor government, the threatening religious freedom bill has been shelved. In December 2021 the Victorian parliament passed laws banning religious schools from sacking or refusing to hire staff based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.

(2) The author of this entry thanks Kay Whitehead, Tim Allender and Rodney Stinson for their comments on the draft entry.’

(3) In 2024, the rights organisation, Equality Australia published the following report. It provides comprehensive, documented and reliable information on discrimination in non-public schools concerning LGBTQ+ students and teachers:

Dismissed, denied and demeaned: A national report on LGBTQ+ discrimination in faith-based schools and organisations. 2024. Sydney: Equality Australia.