Whilst realising the difficulties of setting up a human relationships programme in many schools, we feel that an unequivocal affirmation of the validity of homosexual relationships is the only responsible course open to educators. Gay students need support and they need it now. … Effective change in the situation for gay students will not be achieved by decree or by mere good intentions. The publication of Young, Gay and Proud is one small step in a long overdue educational campaign. Real change will be a long term process in which all of us who have helped perpetuate the cycle of oppression of our gay students, whether actively or by default, seriously examine our attitudes–and where necessary, make a conscious commitment to risk stepping out of that role. We’ve all got a lot of lies to unlearn.

The Booklet Collective, Melbourne Gay Teachers’ and Students’ Group, August 1978

Although various activist groups for gay and lesbian liberation were well organised and active by the late 1970s, law reform was slow in coming in the Australian states, and homophobic violence and discrimination continued through the period. Radicals from a number of ideological backgrounds from the late 1960s began to include greater sexual freedom as part of various liberation programs. This coincided with the development of second wave feminism, and controversies about the degree to which laws might regulate bodies, behaviours and persons.

The extension of the argument for sexual freedom to youth—teenagers/adolescents—was always going to be controversial. As minors, youth were constrained by their parents, schools and numerous laws. These laws variously defined the ages of consent, gaining a driver’s licence, getting married, joining the armed services, leaving school, going to prison, voting in elections, and so on.

The closest that Education for Complete Living (1938), the most significant of the mid-twentieth century publications on educational reform had come in terms of addressing sexual freedom and sex education occurred in a paper by Harold Rugg. His comments concentrated on the harmful effects of the masturbation prohibition. He argued that youth delinquency, and in particular youthful thieving, could be related to the shame that was inspired in young people by adult attempts to discourage youthful masturbation. The shame according to Rugg was apparently more damaging than the practice itself.

In so far as sex education was an issue during the 1940s to 1960s, it rarely addressed homosexuality, and where the issue was addressed the treatment was most likely negative. Most official attempts at sex education were bland, and were often left to the mainly ineffective efforts of movements such as ‘Fathers and Sons’ and ‘Mothers and Daughters’.

An important precursor: The Little Red Schoolbook (1973)

In 1973 an Australian edition of The Little Red School Book by Soren Hansen and Jesper Jensen was published. It purported to tell the truth about the hypocrisies and unspoken facts associated with schools and the management of young people. The book was banned in various schools and departments of education. For example, a Liberal federal  government cabinet minute from 1972 addressed the issues. Because the booklet was already being published in Australia, it had escaped the power of federal customs to prohibit its entry.

government cabinet minute from 1972 addressed the issues. Because the booklet was already being published in Australia, it had escaped the power of federal customs to prohibit its entry.

The Little Red School Book has a small section on homosexuality, wedged between sections on pornography and venereal disease. Nevertheless, its readers were told that at least ten percent of the population have some same-sex attraction, and that the love they felt towards others of the same sex was real, even if homosexuals made love in different ways. Despite male homosexuality being illegal, readers were assured that most same sex relationships were stable and that homosexual marriages would be recognised in the future. There were many more ways that people could live together than in a standard family. An address was given for Gay Liberation in Australia and readers were told that being different was not the same as the charged term, being ‘abnormal’. Good advice was given on the problems of obtaining reliable advice from adults, and books on the subject from librarians.

The book was condemned by the Catholic Weekly and banned altogether in Queensland. In Victoria, copies were seized from 150 shops by the Vice Squad of the state police. Nevertheless it it was widely distributed across Australia to the concern of many parents and school principals.

Young, Gay and Proud (1978)

Five years after The Little Red Schoolbook, an autonomous collective of the Melbourne Gay Teachers and Students Group published the 60 page booklet, Young, Gay and Proud. In that five year period across Australia, the existence of gay and lesbian teachers and students, mainly in secondary schools and universities, had publicity from time to time. In some cases campaigns for the right to information, and struggles against various discriminations had occurred.

Front cover of the booklet

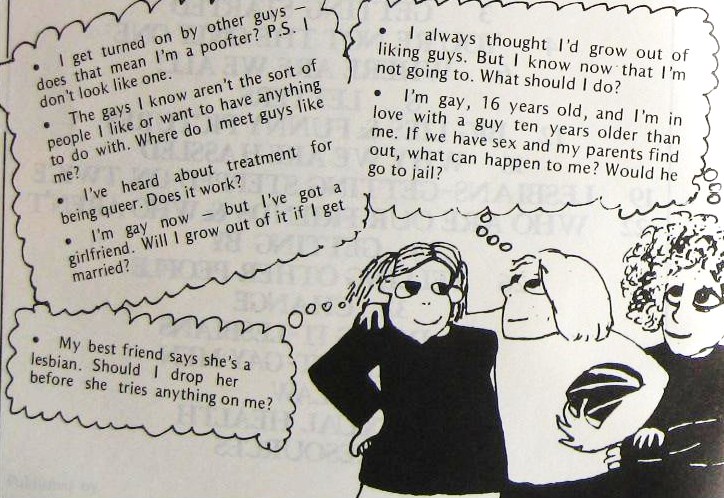

The booklet told stories about the different ways young men and women discovered their homosexuality. It adopted an advice column approach, for example: “I always thought I’d grow out of liking guys. But I now know that I’m not going to. What should I do?” (p. 1). The booklet was liberally illustrated with drawings and photographs, though they were not of a high quality.

The text assured young people that they were not alone, and the Kinsey Report was used to quantify the fact. Coming out as gay, at least to trusted friends, was advised. This would make it more likely that one could be put in touch with others. Where young people’s friends had condemned them as “sick” and “queer”, they were encouraged to think of the accusers as the ones with the problem—and to seek a wider and more supportive friendship group.

Three pages were spent disabusing readers of common, but false assumptions about gays (pp. 13-15). These included the supposed prevalence of short-term uncommitted relationships, the myths about gay men having weak fathers and dominating mothers, lesbians being so because they could not find a man, lesbians hating men in general, gays wanting to “get off” with straights, gay men being frightened of women and hating them, gay men and women wanting to convert straights, and gay men and women inevitably leading sad and lonely lives. (The word “lesbian” was sparingly used early on in the booklet—“gays” and “gay people” were used as including gay men and lesbians.)

An analysis was given of why gay people were oppressed, including an argument that psychiatry had taken the place of the church in oppressing gay people. The new ‘sin’ was deviance or abnormality. The argument was made that lesbians were doubly oppressed for being women first and lesbians second. An argument was made for joining groups and developing political action to fight oppression. There was a special section on telling ‘Mum and Dad’.

The most controversial sections of the booklet no doubt were the pages on how to have sex (pp. 35-42). For males and females, learning the pleasures of masturbation was advocated, and then limited advice on having sex with others was given, including an argument about the taking of passive and active roles. Relevant legal advice was given regarding young people as minors, and dealing with police. There followed a substantial section on sexual health and venereal diseases. The booklet was published before the AIDS/HIV epidemic.

Inventive text and illustrations to get the message across

Young, Gay and Proud concluded with the positive story of ‘Gary’ who, after the struggle of coming out, thought his life was on the right track. Then there was a page of where to find helpful resources, bookshops and libraries. Certain books were recommended. The writers also printed a separate six page rationale and guide for using Young, Gay and Proud. This was aimed at teachers, counsellors and parents of gay and lesbian students.

After the event

In Victoria, Young, Gay and Proud, received considerable media attention, most of it negative. Member of Parliament, Jeff Kennett, regarded the booklet as proselytising. Evangelical Christian churches and organisations campaigned against both it, and any sex education beyond the facts of human reproduction. The booklet was not banned in Victoria, but the Department of Education told secondary school principals to ensure books that fostered homosexual behaviour were not available in school libraries (Angelides, 1978).

Sex education in schools that included straightforward discussions and advice about homosexuality remained a difficult area for many jurisdictions. In 2009, Carmody reported that gay and lesbian youth continued to feel excluded from most sex and health education. There was also evidence that substantial numbers of youth suicides continued to occur as a result of conflicts concerning sexuality. In 2014 nongovernment schools in Australia retained exemptions from anti-discrimination laws that allow them either not to hire, or dismiss gay and lesbian teachers. Young, Gay and Proud was a remarkable initiative in Australian educational publishing.

Note:

In 2024, the rights organisation, Equality Australia published the following report. It provides comprehensive, documented and reliable information on discrimination in non-public schools concerning LGBTQ+ students and teachers:

Dismissed, denied and demeaned: A national report on LGBTQ+ discrimination in faith-based schools and organisations. 2024. Sydney: Equality Australia.