The Commission on Primary, Secondary, Technical, and Other Branches of Education was appointed in New South Wales in early 1902. Commissioners George Handley Knibbs, University lecturer, and John William Turner, Headmaster of Fort Street Model School, travelled widely in Europe and America enquiring into education for the purpose of reforming education in New South Wales. This important Commission, the travels and observations of the Commissioners, and the reports they presented had a major and lasting influence upon the education system of the State.

Context

George Handley Knibbs c1898. Source: State Library of New South Wales ML 524

The appointment of the Commission occurred within a context of agitation for reform. The turn of the of the century witnessed a growing concern in Australia that the various state systems lagged behind educational systems overseas and had failed to take into account new ideas about education. These were often referred to as the New Education. They enjoyed a transnational circulation in this period through published books and journal articles and the reports of educators from many countries travelling to observe systems elsewhere.

Western Australia had reorganised its educational system in the late 1890s and Victoria was entering upon a period of reform instigated by the report of the Royal Commission on Technical Education but New South Wales appeared to have stagnated. At a conference of the Public School Teachers’ Association of New South Wales in June 1901, Professor Francis Anderson, Professor of Logic and Mental Philosophy at the University of Sydney, delivered a speech recognised by both contemporaries and later historians as marking the beginning of an educational renaissance in New South Wales.

John William Turner. Source: New South Wales Teacher and Tutorial Guide, February 1904

Anderson was a masterful speaker who captivated his audience with subtle humour, irony, and persuasive argument. He attacked those, including members of the current government, who persisted in the ‘parrot cry’ that the state possessed the ‘most perfect system of education in the world’ (Anderson 1901, p. 5). Elementary education was neither fully compulsory nor free, the curriculum needed radical alteration, the examination system, understaffing, and large classes forced the teacher to adopt methods which should be ‘condemned as mechanical, and even vicious from the point of view of true education’ (pp. 6-9). He gave attention to the urgent need to reform teacher training, forceful in his extensive criticism of the pupil-teacher system and emphasising the importance of highly trained teachers capable of bringing ‘enthusiasm, intelligence, inspiration, and life’ to education (p. 22ff). The audience was enraptured and excited, applauding, cheering and laughing.

Attorney General Bernhard Wise also spoke critically at this conference, referring satirically to the system that thought itself ‘the best in the world’, ridiculing the salary received by many teachers, and criticising the pupil-teacher system of training. This public criticism by the Attorney General must have been unwelcome to Premier John See and Minister for Public Instruction, John Perry.

Parliament debated the reform of education in the following months and the Opposition made use of Anderson’s arguments. Anderson spoke again at a public meeting in November. A deputation was formed to meet the Premier and the Minister. Perry reacted defensively and with hostility. He told the deputation that he had already decided to appoint a commissioner or commissioners to travel abroad (Educational Gazette, January 1902 p. 169). Perry’s hand had, in fact, been forced.

Travels of the Commissioners

Knibbs and Turner left Sydney on 12 April 1902 and travelled through the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Bohemia, Austria, Hungary, the United States and Canada. Everywhere they spoke to educators and policy makers, visited schools and other educational institutions, and read the appropriate literature on education policy and practice. The Commissioners arrived back in Sydney on 23 February 1903 and began analysing their observations and writing their reports. Late in 1903 the First Report, addressing primary education, was presented to the Governor and the State. Reports on secondary education and technical education were published in October 1904 and September 1905 respectively.

Knibbs, surveyor, lecturer, and later Commonwealth statistician, was a visionary reformer whose progressive beliefs pervaded the reports. He argued the importance of education for national development:

The educational system that successfully aims at building up noble, vigorous, purposeful, and able citizens, is a system that creates national wealth, and begets national force; hence it is the foundation upon which every true patriot will hope to build up the future of Australia, and to consolidate the interests of the Empire (NSWLA 1904a, Summary p. 70).

Knibbs was interested in the individual child and the need for education ‘to make the most of each child as he stands, not to mould him in conformity to some stereotyped ideal’. Like Anderson, Knibbs condemned the educational situation in New South Wales at length.

Turner was appointed to the Commission from within the Department, presumably endorsed by Perry as a counter to the perceived impractical idealism of Knibbs. Knibbs and Turner wrote and took responsibility for separate sections of the reports and acknowledged that they differed in some conclusions but stressed they were in substantial agreement as to the important issues (Summary p. 7).

The First Report: Primary education

In presenting the Interim Report of the Commissioners on Certain Parts of Primary Education, the Commissioners stressed the urgency of reform in this area. The Report was over 600 pages and consisted of two sections, the first containing an introduction, summary, and recommendations, followed by 58 chapters dealing with particular countries and topics. Every conceivable aspect of education received attention, focussed upon the need to reform the system in New South Wales. Knibbs stressed that nothing short of a ‘complete reformation’ was necessary and the conclusions and recommendations made were many.

The Commissioners recommended an expansion of kindergarten classes, taught by specially trained teachers, into every elementary school. New subjects including manual training, natural science and physical culture should be introduced to every class of the primary school while the content and method of other subjects needed to change. The Commissioners not only recommended reform, but provided extensive details of how each subject was taught in many specific school systems in other countries.

New subjects and new methods required teachers who were specifically educated in teaching them. The reform of teacher training was prominent within the report. The Commissioners’ basic recommendation was unequivocal: the pupil-teacher system needed to be abolished and replaced by previous training at a professional training college of the highest standard. Again Knibbs and Turner provided case studies of teacher training in other countries.

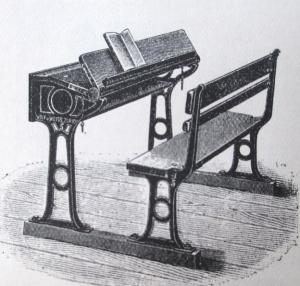

Zurich School Desk. Source: First report, p. 432 (Main section)

School hygiene, buildings, furniture and equipment needed drastic improvement. Instead of several classes being rigidly taught in one room, as was the situation throughout larger schools in New South Wales, the Commissioners stressed the need for one separate room for each class. That room needed adequate lighting, heating and ventilation, and desks which provided back support for the growing child. Specially equipped rooms for manual work, physical education, cooking and science would be necessary as would a library.

Reception

A one day conference of Departmental officials, inspectors, and teachers discussed the First Report in January 1904. Perry, still Minister of Education, defended the present system, and was at times quite critical of Knibbs and Turner. Other speakers continued the defensive tone as Knibbs and Turner became understandably offended and frustrated. Inspector Peter Board was more constructive, urging logical consideration of the report and explaining how some of the proposed reforms could be approached. Board had also travelled to the United Kingdom and Europe in 1903 and written a short paper on educational reform (Board 1903). Board had begun to assume the prominent role he would play in shaping the future of education in New South Wales.

One positive outcome of the January conference was the calling of a second, larger conference to be held in April. The report also set in motion considerable preparation for change within the Department. A committee, which included Inspector Board, produced a new Syllabus of Instruction to replace the old Standard of Proficiency. This syllabus was released to schools in late February 1904.

The Conference of Inspectors, Teachers, Departmental Officers, and Prominent Educationists opened on Tuesday 5 April and continued until 15 April 1904. The proceedings were open to the public and the press and attracted large attendances. Many of Knibbs’ and Turner’s recommendations were discussed, debated, sometimes amended, moved and carried. The resolutions represented incredible change for the system of education in New South Wales. They included abolishing the pupil-teacher system and replacing it with previous training, establishing close links between the University and a newly constituted training college, extending kindergarten classes, introducing new subjects, and providing physical improvements to classroom design and hygiene.

Teachers crowded the hall on 11 April, eager to learn more about the Syllabus of Instruction. Knibbs supported the Syllabus, which had been prepared before the Conference and without his direct input, as ‘a step in the right direction’ but was critical of its lack of detail. He stressed the need for programs to guide teachers, most of whom lacked systematic training in the history, theory and psychology of education. The Syllabus was subsequently revised in June 1905 to include a section of notes which met the call for ‘type’ programs.

One of Knibbs’ recommendations was for the appointment of a Director of Education who would coordinate a system of education within the State that included primary, secondary, and technical branches. Perhaps he considered himself the appropriate candidate. When Acting Under Secretary Frederick Bridges died in November 1904, there was uncertainty as to his successor with Knibbs, Turner, and senior Departmental officials being contenders (Crane & Walker 1957, p. 20). Yet Peter Board had clearly emerged as a leader at the Conferences in 1904. Eager to support reform, the newly elected Premier, Joseph Carruthers, bypassed the seniority principle to appoint Board as Director of Education and Under Secretary of the Department in February 1905. Turner was appointed Assistant Under Secretary and Knibbs the Superintendent of Technical Education.

The Second Report: Secondary education

There were four state high schools in New South Wales in 1902 and a prevailing belief that the State was only required to provide elementary education for most children. The Report of the Commissioners mainly on Secondary Education was published in October 1904. The Commissioners argued that secondary education was essential as preparation for higher forms of education and for preparing teachers for entry to training college. Secondary education needed to be part of a coordinated scheme of education, ‘an integral part of a complete educational system, which every developed country should possess’ (NSWLA 1904b, Summary p. 2). Once again New South Wales lagged shamefully behind the educational systems of Europe and America.

The Commissioners took issue with the widely held view that secondary education was unimportant for the majority and that it could be dealt with by the private institutions that had conventionally provided it for those who wished to proceed to the University. That view would change if secondary education’s relation to general efficiency in industrial and commercial enterprise was adequately understood. In countries with coordinated systems of education, secondary education had a far reaching effect upon both higher education and primary education. The Report included details of those systems observed in the countries visited along with the programs of work in various secondary schools. It was not recommended that New South Wales blindly follow another system but other systems could act as guides. Knibbs provided a suggested outline of a coordinated scheme in a complete educational system (Summary pp. 11-12).

Swiss School Kitchen. Source: First report, p.423 (Main section)

Despite the proposals of the educational conference of April, Knibbs wrote that the education of Australian youth would remain distinctly inferior without the radical reform of secondary education. This represented a dangerous situation:

Let it be clearly recognised that nationally we dare not accept the situation as it stands, that no units in the British Empire can afford to be inferior to Europe and Japan in the matter of education, and we shall face the difficult problem of educational reform with more earnestness. Not to do so would be national insanity (Summary p. 8).

The Third Report: Technical education

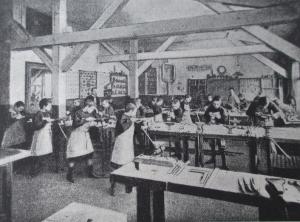

The Report of the Commissioners on Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial, and other forms of Technical Education was presented in September 1905, after the reforms to primary education had commenced. Once again, the introductory section stressed the need for a coordinated system of education in which technical education had an important place (NSWLA 1905, Summary p. 4ff). The foundation of technical education should begin in kindergarten with manual exercises, continue in primary classes through manual training and a practical orientation within other subjects, be provided for in specialised post primary schools and, after that, specialised colleges and university courses. A coordinated system would eliminate the inefficiency of the present system in which college and university courses were hampered by the lack of adequate preparation of students. Primary school teachers needed training in technical subjects and the higher courses required specialist teachers who were educationalists and not merely artisans or workmen.

Manual instruction in a French primary school. Source: First report, p.94 (Main section)

Technical education in New South Wales was seriously defective in comparison with overseas countries. Its meagre funding indicated ‘public indifference to one of the most important factors in our national life’ (Summary p.14). Knibbs recommended that advanced forms of technical education should be placed under a Director-General of Technical Education directly responsible to the Minister. This recommendation would remain unrealised.

Turner provided a list of specific recommendations regarding technical education in New South Wales. These included the establishment of evening continuation schools, district schools which would include elementary agriculture, the provision of additional specialised courses within superior public schools and the establishment of a manual training high school, a commercial high school and a domestic science school for girls. (See entry on differentiated schooling.) Some of these recommendations were acted upon while Knibbs was Superintendent of Technical Education (1905-June 1906) and subsequently when Turner replaced him (1906-1912). It was not until after Turner retired that the whole system was reorganised.

Implementation

Many of Knibbs’ and Turner’s recommendations regarding primary school education were endorsed at the conference in April 1904. A significant period of reform commenced after Peter Board became Director and Under Secretary. By the end of 1907, Board reported that almost every section of primary education had come under review and been recast (Annual Report 1907, p. 28). It was now time to consider secondary education. While Board developed his own ideas and took notice of developments in education subsequent to 1902, the vision and recommendations of the Knibbs and Turner reports remained firmly in the background as a guiding influence. Knibbs’ conception of the necessity for a thoroughly coordinated system of education featured in Board’s schemes for the development of secondary and technical education.

The Department built and opened new high schools after 1906, their number increasing from four to twelve by 1912. District schools, which offered a two year course beyond the primary, opened in country centres to augment the provision of post primary education in superior public schools. Public interest in the provision of education beyond the primary level was obviously increasing. Board developed a comprehensive scheme of secondary education for New South Wales which took effect in 1911. In 1912 Board approved a revised system of technical education. After six years of primary school and the achievement of a qualifying certificate, a pupil could proceed to a general high school course, a junior technical course, a commercial course, or a domestic science course. These courses were in turn linked to higher technical courses, the Teachers College and the University.

Professor Francis Anderson was well pleased with the advances made in education between 1901 and 1914. The Knibbs and Turner Commission had produced an ‘encyclopaedic report’, which had led to the surrender of the policy of passive resistance on the part of the Minister and Departmental officials:

The history of education in New South Wales from that time to the present has been a record of consistent, and on the whole successful, attempts to construct a flexible, coherent, and comprehensive national system … . (Anderson 1914, pp. 521-2.)

The changes which followed the Knibbs and Turner Commission profoundly influenced education in New South Wales. Knibbs’ contributions to the reports demonstrate a sustained progressive ideology and a mastery of educational philosophy which render the reports unique and important documents for educational history. The wealth of detail relating to educational systems and institutions of countries throughout the world indicates a continuing significance of the reports for comparative educational history.

NOTE:

The three Knibbs and Turner reports (listed below) are available digitally through the National Library of Australia.