The design, production, and use of desks, tables, and chairs, perhaps the most obvious objects within classrooms past and present, accompanied changing ideas of pedagogy and physical health from the late nineteenth century to the present day. This was the case in New South Wales along with other Australian jurisdictions and other countries. The school’s physical context, including objects that comprise a classroom, influences the experience of schooling for teachers and children as well as the teaching and learning that occurs. Studies of common classroom objects such as desks, tables and chairs demonstrate how they begin as “objects crucial to innovation” (Lawn and Grosvenor, p. 7), later become targets of criticism and, finally, obsolete. Individual objects end up discarded, with some re-used in new contexts, including museum displays.

In New South Wales, the proudly centralised design, production and distribution of school furniture was superseded by privatisation and the procurement of furniture by contract in the neoliberal economic and political context of the late twentieth century.

Compulsory state education, 1870s-1900

From the 1890s, educational reformers advocating changes to schooling were critical of the seating provided in the larger state schools throughout the Australian colonies (after 1901, States of the new Commonwealth). It is hard to find a description of the long desks and seats or benches that is not negative with regard to the type of education such furniture accompanied and the effect of this furniture on the physical well-being of the child. An account from 1880 is more favourable:

The desks in all schools [Victorian state schools] are arranged in parallel rows, the front row on the floor, and each successive row raised a few inches higher. The seats are attached, and underneath the desks are shelves for holding books, slates, &c. The gallery is arranged with easy steps, and the seats are fitted with sloping solid backs.

That description accompanied the Victorian State School Exhibit at the Melbourne International Exhibition.

At the present-day Schoolhouse Museum in New South Wales, children may sit in a gallery similar to that described above, in the original school building at North Ryde:

1877 schoolroom at NSW Schoolhouse Museum of Public Education. Available Flickr, reproduced with permission of the Museum.

The room has been authentically furnished with early public school furniture. The cupboard (book press) and teacher’s desk are Australian red cedar whilst the long-toms (desks) are pine … Built as a single schoolroom, pupils from 1st to 5th Class were taught collectively by one teacher, often assisted by a pupil-teacher (trainee)… The 1st Class students sat in the infants gallery writing on slate boards perched on their knees. (https://www.schoolhousemuseum.org.au/about/schoolrooms/; accessed 7 March 2022)

School furniture production in New South Wales, 1899-1911

In the late 1890s to 1911, the long school desks and bench seats were produced in a carpentry shop located on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour. Boys from the industrial school ship, the Sobraon, also under the authority of the New South Wales Department of Public Instruction, were apprenticed to produce school furniture, with one aim being to give the boys a useful trade. The furniture was of high quality, made from Australian cedar, Dorrigo pine and silky oak. As reform progressed, the shop produced many items including new style dual desks, although due to restrictions of the site, the new desks were also produced by outside firms as were all of their cast iron supports, or “standards”. When the Sobraon ceased to operate in 1911, and the Commonwealth Government took over Cockatoo Island for naval construction, in 1912 the Department of Education purchased a factory at Drummoyne which would be in use until 1980.

Educational reform in NSW, 1900-1920s

As educators throughout the developed world became aware of the pedagogical ideas and reformed practices that were often referred to as New Education, criticism of existing policies and practices grew. In New South Wales the desire for change led to the appointment in 1902 of two commissioners, George Handley Knibbs and John William Turner. They travelled overseas to observe schools and schooling, recommending changes to the education system. Their brief included “Material Equipment”, meaning school buildings, furniture and teaching materials. In their report, Knibbs was very critical of the seating provided in New South Wales, arguing that it produced myopia, spinal curvature, and, in combination with crowding, poor ventilation and temperature control, represented a serious threat to the “physique of the Australian people” (First report, Summary, p. 64). He called for desks and seats that supported the back of the growing child, allowed a proper distance between eye and paper, and that were proportional to the height of the child. Pedagogical considerations indicated that desks should be arranged to allow each child to move in and out of the seat without disturbing others and, additionally, they needed to be movable. It was important that the desks be part of a separate classroom for each class group, unlike the existing situation of large school rooms containing several groups and designed for supervision of pupil teachers by a headmaster.

At the educational conference held in April 1904, Knibbs and Turner’s recommendation for dual desks (desks for two children) was discussed. James Wigram, government architect to the Department of Public Instruction, favoured Canadian designs as alternatives to the Swiss model provided by Knibbs and Turner but further advised that an Australian design be developed and locally produced by the Department’s workshops. That would reduce expenditure. Turner endorsed his proposal: “Let us make them ourselves from our own timber. Let us improve on the Swiss and on the Canadian patterns” (Conference of Inspectors, Teachers, Departmental Officers, and Prominent Educationists, April 1904, p. 212).

From 1904, production of dual desks began, although the old long desks were also continued. When Birchgrove Public School opened in July 1904, some classrooms contained “the ordinary style of desks and forms” while others had “dual desks, these being the latest designed for the very young”. In early 1905, newspapers reported the replacement of galleries in schoolrooms with “dual desks and seats”. When a new school opened at Guildford, the enthusiastic report of its opening noted that seating throughout consisted of dual desks and seats with backs, suiting the height of children. Later that year, the Department of Public Instruction called for tenders to supply 1000 sets of dual desk and seat standards “in accordance with the new pattern, as approved by the Education Commissioners”.[1]

School Furniture Workshops, Drummoyne, 1913

After the move to Drummoyne, the School Furniture Workshops continued to make old style long desks and forms alongside the new dual desks, indicating a lengthy transition period. The actual style of the dual desk is pictured in a photograph of furniture ready for despatch in 1913 while a similar desk is now part of the Powerhouse Museum collection.

School desks made by NSW Department of Education’s Furniture Workshop. 86/870D.

Collection: Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. Gift of Department Of Education, 1986. Photographer unknown. Reproduced with permission.

Although the desks were produced in several sizes, they were not designed to be portable, as Knibbs had recommended. Instead, they were fixed to the floor in rows, produced with the seat of one attached to the table of the one behind. As such, they became a dominant feature of classrooms for decades, despite becoming increasingly criticised by reforming educators.

Montessori tables and chairs

By 1919 the Workshops were producing what were called “Montessori tables and chairs”, in several sizes. These were lighter than the older kindergarten tables and chairs, and followed enthusiastic promotion of Montessori education by Martha Margaret Simpson, Infants Mistress of Blackfriars Practice School, lecturer at Sydney Teachers College and in 1917 appointed the first female inspector in New South Wales. Simpson believed that furniture was crucial for introducing new principles and methods of teaching. She insisted that children should be able to move about freely and that classrooms contain small tables and chairs that children could lift and carry. The flexibility of such furniture would allow arrangement and rearrangement to cater for different kinds of activity (Simpson, 1914, p. 10, 35). Her recommendation that the Department produce tables and chairs made of light, cheap wood for every infant school room was evidently acted upon, shown by actual orders for this furniture.

![Toy making, Stanmore Public School, 1919. Source: NSW State Archives and Records: NRS-15051-1-30-[1706]](https://dehanz.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Toy-making-Stanmore-Public-School-1919-15051_1_30_a047_000869-300x228.jpg)

Toy making, Stanmore Public School, 1919. Source: NSW State Archives and Records: NRS-15051-1-30-[1706]

1920s to 1940s

In the 1920s, reform of education stalled in New South Wales, and the Depression of the 1930s meant little money was available to refurbish the public schools. Reforming educators, however, remained interested in furniture, and would have been aware of an American publication, School Posture and Seating by Henry Eastman Bennett (1928). The term “ergonomics” was not used, but Bennett’s aim was to make a “contribution to the science of sitting and seating” (iv). Using statistical studies, he considered optimal seat heights, desk heights, spacing between seats and desks, and back support. He argued that school furniture had to be movable, in contrast to the tradition of screwing seats to the floor. However, for settings beyond elementary school, Bennett favoured a single desk unit over separate tables and chairs, as long as the unit was movable, hygienic, comfortable, attractive in design and finish, durable and economical.

Other educators in many countries increasingly favoured separate tables and chairs as necessary for modern schooling. In Australia, a post-war booklet from the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), School Buildings and Equipment (1948) urged the replacement of fixed desks. Classrooms designed for activity needed furniture that was light, strong and movable, allowing the floor to be quickly and easily cleared for varied activities. The desks in most schools, the authors continued, were a hindrance to any activity programme, and their dark, varnished surfaces were unpleasant. Light coloured wood, such as Victorian ash, was preferable, pleasing in appearance and restful to the eyes while well designed chairs were important for physical comfort and skeletal development.

Furniture Workshops and the contribution of H.W. Oxford, 1945-1960s

The end of World War 2 saw a rising demand for new school furniture amidst a serious shortage of building materials. Even as the shortage eased, the Workshops could not keep pace with requirements of the schools, spurred by the growth in population and children reaching school age. Throughout the 1950s, furniture production in the Workshops was supplemented with furniture from private manufacturers, but this was considered unsatisfactory, and the proportion produced by private contractors decreased by 1960. The lack of cast iron standards led to an expanded production of timber tables and chairs from 1949.

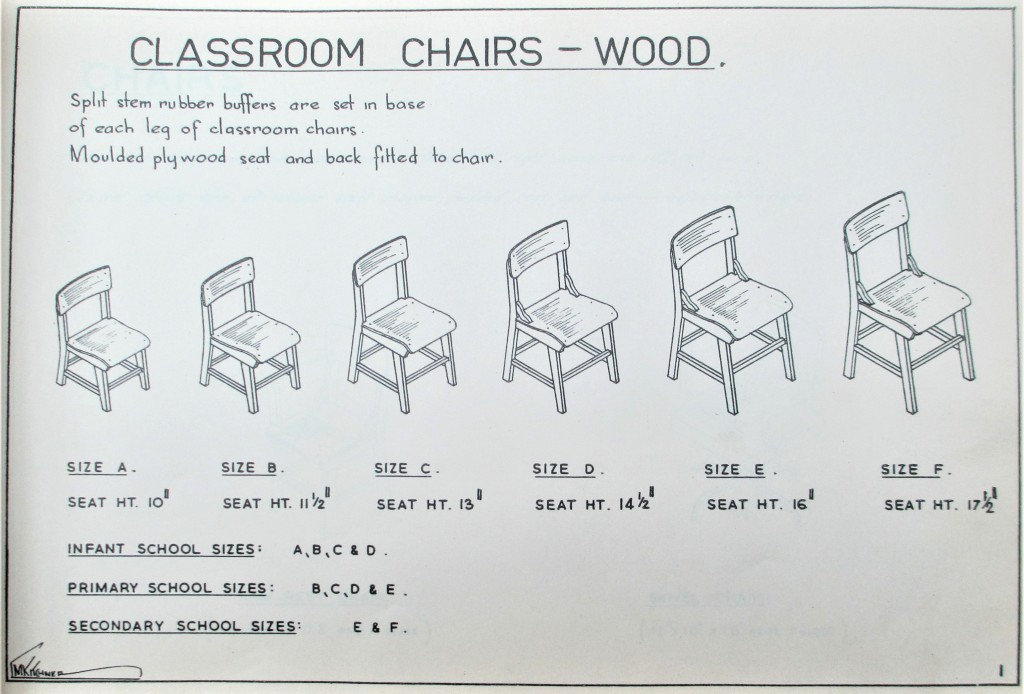

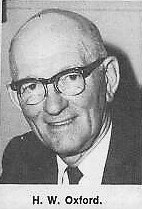

Herbert W. Oxford, a lecturer from Armidale Teachers College, was seconded to the Education Department’s head office in 1945 and took charge of the research, design, and production of school furniture. In 1949, and again in 1965, he organised surveys of school children, the results of which informed the sizes of the chairs and tables produced. At first there were 8 sizes of furniture produced, later reduced to 6 and graded from A for very small children, to E and F for secondary school students. Oxford travelled overseas in 1952 and 1963 to study all aspects of school furniture. His contribution to schooling in New South Wales is now largely forgotten, but he was in fact an early expert in the field of ergonomics, dedicated to what he called the study of the human relationship which existed between the school child, chair and table.

School Chairs A to E. Source: New South Wales. Department of Education (1959) School Furniture, p. 1

After his trip abroad in 1952, Oxford reported to the Minister of Education, R.J. Heffron. He concluded that the Department had acted wisely in abandoning production of the dual desk, as mobile tables and chairs were now widely supplied to schools in other countries. He made recommendations in regard to machinery, timbers and lacquers, the introduction of metal in the production of chairs and tables, the possible use of plywood for chairs, and of sheet plastic such as Formica for table-tops. Light coloured timbers and natural colour finishes were recommended.

Oxford noted that no other education authority in any of the countries visited in the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States possessed their own furniture workshops. New South Wales was fortunate in being able to design and construct furniture to its own specifications, ensuring the standard of workmanship. Oxford, and the Department more generally, remained proud of their centralised furniture establishment. According to Oxford, many administrators envied the facilities he described, but in the United States he was told this situation would be considered “socialistic”, and in England he was told that unions would object (Oxford, H. W. Report on School Buildings, School Equipment and School Maintenance Overseas, 1952).

In 1953, land and large sheds at Sheas Creek, St Peters were acquired by the Department and became the Furniture Centre for the assembling and distribution of school furniture. The Workshops at Drummoyne continued as the main factory, and a third body, the Furniture Services Branch, was established in 1955 in the grounds of Five Dock Public School, to take responsibility for processing orders for the supply of furniture, keeping records of furniture in all the schools of the State, and attending to maintenance and repair.

Furniture Workshops Jubilee 1963

Fifty years of production by the Furniture Workshops was celebrated in 1963 in a Departmental booklet. The author praised the reorganisation of the 1950s that had resulted in

one of the largest furniture factories in the Southern Hemisphere, a re-vitalized establishment, a marked increase in output, a definite fall in the costs of production, and an obvious improvement in staff morale (Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, p. 9).

New South Wales. Department of Education (1963), Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, 1913-1963. Sydney: Government Printer.

The booklet’s cover featured the newest furniture being supplied to secondary schools: single tables with metal frames and synthetic veneer surface. Teachers favoured the elimination of the under shelf, as these had been used for rubbish. Primary schools continued to receive dual tables made of wood, and chairs of wood and plywood. A Furniture Review Committee, headed by Oxford, considered “trends” in both design and construction and tested samples before recommendation. Furniture for children with disabilities was one area of testing and supply in 1963.

Throughout the 1960s, plans were made to combine the three establishments (Workshops, Centre, and Services Branch) into one large factory complex. The Department therefore acquired industrial land at Smithfield, a suburb in Sydney’s west. (The actual address of the factory when completed was Wetherill Park). Between February 1964 and September 1965, Oxford chaired a Furniture Centre Planning Committee which attempted to define the furnishing requirements of schools fifteen years in the future, and to plan the new Centre accordingly. A site plan was prepared, and Oxford presented his report in late 1965. However, actual building on the site did not commence until the late 1970s.

School Furniture Complex, Wetherill Park, 1980-1993

The School Furniture Complex, located at 3-7 Davis Road Wetherill Park, manufactured an increasing range of furniture for the State schools. In addition, it supplied non-government schools and began production of general office furniture for government departments. Some furniture was made externally, to specifications, by other companies including Sebel, a company that remains proud of its history of replacing wooden chairs in schools with polypropylene. The Complex also arranged servicing of existing furniture throughout New South Wales. It included a large showroom and additionally sold furniture no longer required in schools to the public. In this way, superseded models of chairs and tables found a place in family homes as children’s furniture.

The Furniture Sub-Committee of the Schools Building Research and Development Group met regularly at the Complex to discuss new designs of furniture, arrange trials of prototypes in schools and evaluate the results. In 1985, for example, it trialled a larger size of secondary school table and in 1988 new designs for tables and chairs for Kindergarten to Year 6 were developed. Computer tables and work-stations, and furniture requirements for the integration of students with physical disabilities into regular classrooms were two of many issues addressed by this committee.1990s – 2000s

Twenty years in the planning and built at considerable expense, the School Furniture Complex operated for little more than a decade. In 1988 a Liberal-National government promised to cut government expenditure. Terry Metherell, Minister for Education and Youth Affairs, appointed Brian Scott to head a complete review of education in New South Wales. Released in 1989, the report included a recommendation to corporatise and eventually privatise the School Furniture Complex. Despite opposition by unions and parents, plans for privatisation proceeded. In late 1993 a private firm, Furniture Australia, took over the operation of the Complex, transferred production elsewhere and the Wetherill Park site was sold.

This sale took place within a much wider context of privatisation of government enterprises. The design, production, testing and supply of furniture to schools ceased to be a state service to education and became part of the market economy. Individual schools became responsible for budgeting and ordering their furniture from Department endorsed suppliers.

Conclusion

While attention to the ergonomics of school furniture remains an area of interest, and catalogues feature ever-evolving designs for classrooms, it is interesting to note a continuing consistency in pedagogical ideas about tables and chairs. A recent document from the Audit Office of New South Wales, “Planning for School Infrastructure” (2017) includes a section outlining features of future learning spaces. In addition to technology such spaces will need “lightweight, flexible furniture that can be easily moved around by teachers and students, creating functional spaces for individual and team work” (Exhibit 15). Classrooms of the future may appear very different to those of the past, but that progressive thinking relating to seating and work-tables is very much the same as what was expressed by M.M. Simpson in 1914, the ACER in 1948, and other educationists over many years.

[1] Balmain Observer and Western Suburbs Advertiser, 23 July 1904, p. 4; Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, 30 August 1905, p. 2; SMH, 24 Oct 1905, p. 8.

![SFC School chairs 1988. Source: SRNSW NRS-4352-13-[10/50401]-S.5000/1775 Pt. 2]](https://dehanz.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/SFC-Catalogue-c1988-768x1024.jpg)