Women’s Liberation badge, 1970s

The revivified feminist and broader women’s movement from the late 1960s were always going to have a major impact on education policy and schools. The disparities and inequalities between males and females were deeply embedded. Commonly girls and boys had different curricula, women teachers were usually confined to less well-paid positions, fewer girls completed high school and graduated from universities and colleges in the tertiary sector, fewer girls than boys were accepted into apprenticeships. Much of the labour market was segmented by gender, with women tending to occupy less well-paid ‘women’s jobs’.

These structural disparities and inequalities were supported by a culture that routinely advocated the confinement of women to a limited number of roles and occupations in families and the broader society. Women were expected to enter the labour force but briefly before marriage. After marriage their major work was to bear children and be ‘house-wives’, looking after children, and relieving their husbands of domestic labour in the home. These social expectations and roles sustained and were sustained by prevailing views about the most acceptable forms of femininity and masculinity.

This gender order had been subject to criticism and disruption for more than a century, including in education, as histories by Theobald (1996) and Lake (1999) among others have traced. From the late 1960s, however, the pressures dramatically intensified, and governments, State and Commonwealth responded.

Australian Schools Commission

In 1972 a reforming Labor government led by Gough Whitlam was elected in Australia. Among its policies was the creation of a Schools Commission whose major task would be to advise on the spending of substantially increased federal funds to improve Australian schools. Schools in government and non-government sectors would receive grants to assist with capital works and recurrent expenses. The Commission would devise special programs whose intent was to assist ‘disadvantaged’ populations in ‘disadvantaged’ schools. The Commission would also seek to improve the quality of teaching, and relationships between parents, communities and schools.

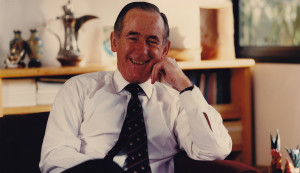

Ken McKinnon, chair of the committee producing Girls School and Society, and the Schools Commission itself

The chairman of the Commission was Ken McKinnon. Of the two full-time commissioners, one was Jean Blackburn who had a history in feminism and social reform dating back to the 1940s. Very early in its life, the Commission decided to address the question of equality of opportunity as it affected girls and women. Not everyone was convinced as to whether girls’ education warranted similar attention to that afforded children from poor families who attended under-resourced schools. For some, the cause of educational inequality was substantially about social class. Girls from well-off families bore nothing like the disadvantages that girls from poor families experienced. Others believed non-English speaking, Indigenous and rural circumstances were the significant factors.

In fact, there never was a Schools Commission program based solely on girls or sex inequality. Nevertheless, the argument was won that the Commission should inquire into the issue of sex-difference as a cause of inequality for girls and women. A study group was established to devise and recommend policy to the Commission. These were its terms of reference:

- to examine the extent of underachievement by women and girls in education and its contribution to the inferior status of women;

- to examine the reasons for this, including community attitudes and implicit and explicit discrimination against women and girls in schools;

- to examine the ramifications of the increasing participation by women in the labour force on Australian education;

- to recommend any program projects and the necessary funding to assist girls so that they have as many careers and life choices open to them as do boys. (Girls, School and Society, pp. 1-2)

Establishing the Committee

The Commission was fortunate in the persons who agreed to become members of the Committee. They, and the consultants who undertook various tasks for the committee, included women who were or would become leading feminists in Australia. The committee included Ken McKinnon as chair, Jean Blackburn (Schools Commissioner), Cathy Bloch (teacher unionist), Jean Martin (sociologist), Elizabeth Reid (Prime Minister’s women’s adviser), Susan Ryan (officer of the national state schools’ parent organisation), Bill Thiele (student counsellor), David Widdup (mathematician and gay activist) and lastly, Daniela Torsh (journalist and feminist activist) as the executive officer. Consultants and research assistants over the life of the committee included Eva Cox, Anne Summers, Teresa Brennan, Clare Burton, Wendy McCarthy, Mary Murnane, Lorna Hannan and Helen Townsend.

Daniela (Dany) Torsh was working on a doctorate on women and education when she was recruited to the Commission and the Committee. Her theoretical study and the bibliographic resources she continued to collect underpinned the Committee’s work.

Writing Girls, School and Society

The Committee commissioned research and received submissions on matters associated with its terms of reference. There were vigorous discussions and drafts that preceded the final publication. The Committee as a whole was responsible for the final report but the chairman of the Committee, McKinnon, signed off on the Report on its behalf.

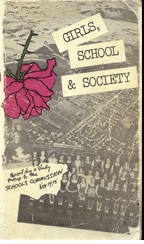

Front cover of the Report

Torsh produced a first draft for the Committee, and elements of that draft survived into the final document. McKinnon and Blackburn thought that the first draft was not suitable for presentation as a Commission report. Blackburn appears to have been responsible for rewriting much of it. Jean Martin may also have been involved in this exercise. Torsh was a more radical feminist than Blackburn. She was disappointed that some elements of the first draft were either toned down or disappeared. David Widdup had wanted more on sex education and sexuality, including the recognition of same sex issues as they might apply to curriculum and wider education. The report would be reformist, innovative and daring but not radical in the ways that Widdup and Torsh wanted. McKinnon and Blackburn, and the Committee as a whole, eventually settled on a draft that would be acceptable to government, and not antagonise too many groups and school systems that had an interest in its recommendations.

The Report

The Report contained 14 chapters that ranged over changing sex roles, sex differences in school and post-school participation in education, the reform of schools as organisations, their curriculum offerings, sex roles and socialisation of teachers and students, sexuality and human relationships, vocational guidance and groups with special needs. The three groups with special needs that received the most attention were migrant, Aboriginal and rural girls and women.

Jean Blackburn, a strong influence on the final shape of the Report

The language of the Report preceded the widespread adoption of the words and developing ideas around ‘gender’ and the ‘gender order’. Sex difference and sex role differences are the crucial words and concepts for the report, but attention was given to the concepts of sexism (see Glossary) and differing forms of femininity and masculinity. Importantly, the Report depends on the view that gender and its regimes emerge historically; they are, in the main, historical constructs. The significance of child-bearing for many women’s lives was not underestimated, but the argument was made that different societies could manage the consequences for women differently. The life-consequences of child-bearing for women need not be pre-determined. Women’s lives were subject to changing cultural, economic and social arrangements. Such arrangements could proceed from reforms in education.

It had become common in the early 1970s among feminists and others of the more radical left to despair of the capacity of schools to be a force for progress or reform in such areas. This issue was live for the Committee producing the Report. The Report decided the opposite: that schools and education systems had to be considered capable of reform, and were in fact, essential agents if it was to occur.

The Schools Commission administered no school systems, so it was not in a position to insist on any particular changes. Instead it used the Report to summarise research, to educate the persons who operated schools and school systems, to advise certain reforms, to advocate further research, and importantly, to insist that the issues associated with sexism and sex inequality be addressed through action at all levels of education: Commonwealth and State, school system and individual schools.

Chapter 14 of the Report outlines its conclusions and recommendations. It argued as a consequence of the problems in education, that girls were much less inclined than boys to ‘see themselves as people able to influence the circumstances of their lives’ (p. 155). The phrase low self-esteem was used and popularised in the Report. Biological differences were quite insufficient to explain a great range of differences between the sexes. ‘What it means to be female or male in a particular social context is largely learned’ (p. 155). It listed the ways that schools often exacerbated inequality between the sexes, and outlined principles for action that schools might undertake. They included the removal of gender-based curriculum barriers, especially those restricting the pathways to a full range of occupations and careers. A series of recommendations about how schools might be assisted to achieve the aims then followed. They included reference to what Schools Commission-based programs, Disadvantaged Schools and Special Projects might do. The Committee argued that all programs of the Commission should be required to address sex-based inequality.

A further set of recommendations provided for on-going consideration and action by the Commission. The Report concluded with a call for change in Australian society more broadly. Australian schools and education systems could only do so much. The over-arching aim was to promote ‘a shared humanity and mutuality between the sexes’ (168). In this sense, the Report addressed the disabilities associated with prevailing forms of masculinity as well as femininity; for example: ‘Deep seated fears of homosexuality in our society, and stronger condemnation of it among males, undoubtedly play a part in what appear to be more severe early sex role shaping of boys than girls’ (p. 15).

Significance and consequences

The Report was published during International Women’s Year (1975), and was an Australian contribution to that event nationally and internationally. Though its analysis and prescriptions may seem rather ordinary in the 21st century, the Report was pioneering in Australia and internationally in the mid-1970s. It advanced reform along the lines it suggested as schools and school systems reacted to it more or less favourably. The Report was resisted by several conservative groups, including persons in the Catholic Church hierarchy who thought it was too radical in its re-imagining of women and their potential social roles.

School girl. Photo by Mike Fox on Unsplash

The Report also needs to be seen as part of an historical process that had already begun. For example, restrictions on the wages, promotion and employment of women, especially married women, in education systems were already being addressed as the Report was produced. Moreover, girls were beginning to equal the retention rates of boys through to the last year of high school.

Eventually there would be units led by women’s advisers in most departments of education in the Australian state governments. Most school systems produced policies around non-sexist education and eventually ‘gender equity’ with some resourcing to give them effect. (See Connell, 1993, p. 514.) Not much later, as curriculum reform occurred across the education systems as a response to growing youth unemployment, equality of opportunity as it related to gender was usually taken into account. The Schools Commission produced a further report in 1985, Girls and Tomorrow. It was circumspect in its conclusions. There had been insufficient progress made from the Report of 1975.

By the end of the twentieth century, for a variety of reasons, but including the Report, gender-based participation rates and access to broader curriculum choices was to a fair degree achieved in schools, but underlying cultures and structures that limited women’s employment, career opportunities and wealth after their school and university years usually remained substantially in place.

Glossary

Sexism according to Girls, School and Society was about ‘the expectation that individuals will be different kinds of people occupying different social positions merely because they are female or male [and] is very like racism which generalises in similar ways from characteristics acquired by birth.’ (G,S&S, p. 8.)