Many national and provincial governments sought to expand access to secondary schooling during the twentieth century. New Zealand was a pioneer of the comprehensive school in its region. There would be a reformed curriculum that could include many more students than an academic elite. The influence of William Thomas was not confined to New Zealand. His reform program had a strong influence on several of the state systems of education in Australia.

In 1974 Henry Field, a former professor of Canterbury University College in Christchurch regretted “that the lives of men and women who have contributed significantly to our national life go unrecorded.” He made reference to a former Director of New Zealand Education (1940-1960) Dr Clarence E. Beeby and to Peter Fraser, the Minister of Education (1935-1940) in the first national Labour government elected in 1935.

Since 1974 however, several scholars have examined the lives, work, and legacies of Fraser and Beeby. They generally agree that these men ought to be regarded as education progressives. Field also argued that William Thomas be studied for his work on curricular reform in post-primary schooling, including his leadership of a national committee, and for his legacy as a persuasive education thinker and advocate.

Educational background, and influences on his thinking

William Thomas was born in Dunedin, into an upwardly mobile working class family on 18 December 1879. His mother sent him to her former primary school in Dunedin, the Union Street School. Thomas’ father, Nicolas, was occasionally absent from his family as he searched for work during the 1880 to 1895 depression. Thomas excelled at his studies and in sports, earning the respect and support of the headmaster, Alexander Stewart.

In 1893 William was enrolled in Standard 6 at Waimate District High School (WDHS). Under the tutelage of the Headmaster, John Smyth, Thomas flourished academically and on the sports field. Smyth was also William’s Sunday school teacher at the local Presbyterian Church. Smyth admired Thomas’ academic aptitude, self discipline, and sporting prowess. William was dux of the school’s primary division in 1893.

Thomas completed his first year (Form 3) in the school’s secondary department in 1894, having excelled in English, Latin, and Mathematics. In the same year he passed the first examination for public primary school teachers. He continued with his music studies, and was recommended by Smyth for a pupil teachership. Such early appointment was unusual but Smyth believed that Thomas’ qualities warranted the action. As a teaching assistant in the school’s primary department, Thomas was regarded as an able and engaging practitioner. The South Canterbury Education Board concurred, and in 1895 Thomas began his formal training as a pupil teacher.

For four years he worked as a pupil teacher in the WDHS. After teaching his classes Thomas studied in the evenings for the University of New Zealand Matriculation (Form 5 University Entrance) Examination and for the final Teachers’ Class D Examination. He gained these qualifications in 1898. At the same time Thomas took early morning and late evening classes with the new headmaster, George Pitcaithly.

Pitcaithly taught Thomas for both education theory and practice classes. In 1899 he was promoted to assistant teacher at the Waimate DHS, moving from there to a teaching principalship in 1900 at the nearby Waitaki Village Settlement School. In his three-year tenure there Thomas distinguished himself with his willingness to experiment with teaching methods (for example, children singing their reading) and his enthusiasm for girls and boys both participating in sports at and beyond school.

Between 1902 and 1903, while teaching full time, he passed several courses for the first section of his BA degree as a distance student of Canterbury University College. The degree was completed in 1906 (in constitutional history and jurisprudence, English, history and political economy, Latin, mathematics, and mental science), while working as headmaster (1906-1909) of Pleasant Point District High School in North Otago. When he left in 1910 for the headmastership of Waimataitai Primary School in nearby Timaru, Thomas had already gained his MA (Hons) degree from the Canterbury University College. He had forged an outstanding reputation as a hard-working teaching principal in the school’s primary department, a secondary teacher of English, and as a talented musician and sportsperson. Thomas was supported in his work, study, and private life fully by his wife. He had married Ethel Jones in 1905.

His principalship at Waimataitai equipped Thomas with many skills which would prepare him for a subsequent career in secondary schooling. With some 400 pupils and nine teachers, the school enabled him to practice his public speaking and organisation. In his time there Thomas demonstrated the value of aesthetic studies (music, singing, and art appreciation) and a redesigned school environment, making it more welcoming and attractive to pupils and community. His reputation in and beyond education communities continued to grow. He was noticed by the Board of Governors of the (two) Timaru high schools when they sought a new rector (principal) for the Boys’ High School in 1912.

After winning the position, Thomas began work as rector in 1913. It was unusual for a primary trained educator to win a secondary school position, given that primary and secondary schools and teachers had rather different purposes and statuses. Thomas’ training may have assisted his application however, because few secondary school staff received training in the teachers’ colleges of the early twentieth century. His prior leadership of a secondary department within a high school, his reputation an educator, his academic qualifications, his known Christian faith linked to good citizenship and general character, likely assisted Thomas’ candidature.

Rector of Timaru Boys’ High School

Thomas’ appointment occurred at a time when enrolments were low, despite free tuition becoming available at many secondary schools from 1903, for primary school leavers who held a Standard 6 Proficiency Certificate. “Higher education” was commonly thought unnecessary for pupils whose parents and teachers did not regard them as academically or professionally oriented. Thomas was alert to this perception, and tackled it by introducing agricultural and commercial courses in the school in 1913.

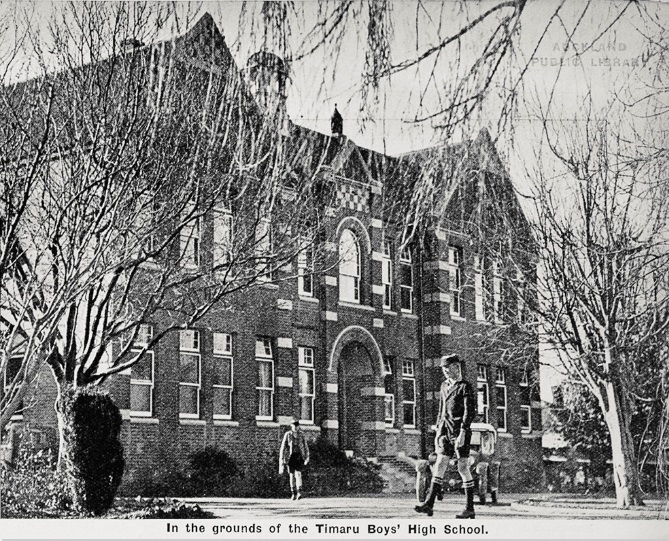

Timaru Boys’ High School (1936). Thomas was Rector here from 1913 to 1935. Source: The Aucland Weekly News, Supplement, July 8, 1936

Thomas’ philosophy of education is evident through the curriculum provision of intellectual, practical, physical, and social activities. He valued academic accomplishments, reporting proudly on the various scholarships that his students won. This was not at the expense of practical studies, as witnessed by Thomas’ support for technical instruction and training from the late 1910s. He opposed any suggestion that staff in the Timaru Technical College and his own school should compete for pupils, regarding this as unhealthy and inefficient. In this respect, and in several others, Thomas’ thinking was similar to that of Frank Milner, the prominent Rector of Waitaki Boy’s High School. Thomas understood that his school had to offer a variety of courses to suit the perceived and real aptitudes, interests, and vocational destinations of boys. At the same time it was important to Thomas that all pupils should have experiences in common while at school. He maintained this stance throughout his principalship in Timaru from1913 to1935.Within two years the roll had doubled. The new courses brought pupils who had been unlikely to remain for more than two years. Thomas retained the professional (academic) course mainly for university aspirants. He recruited more boarders. Efforts by him and his staff to make the school environment more appealing to adolescent boys paid handsomely. Boys were attracted to the school by the wide range of courses and the extra-curricular offerings including cricket, rugby, and school concerts. The agricultural course had a practical component, with land reserved for experimental purposes. Enrolments increased further when primary school-age boys began to attend the high school’s newly opened preparatory classes from 1915, as “fee-paying scholars”. These classes were seldom viewed positively because primary school authorities usually saw them as an unwarranted intrusion into their territory.

William Thomas. Image courtesy of the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch. No: 19XX.2.5246

Criticisms of New Zealand secondary schooling

Thomas believed that too few opportunities existed in New Zealand secondary schools for pupils to study music, singing, art, drama, woodwork, and to undertake physical activity with the view to improving a boy’s physique and deportment. He was convinced that such activities provided “a splendid outlet for superfluous energy”, relieved tedium, stimulated the adolescent mind, and helped develop “the emotional and spiritual side of a boy’s life.”

Thomas was concerned that the conventional secondary curriculum emphasised some subjects to the detriment of others. In the 1920s he argued that his was apparent in the examination regulations. Academically oriented schooling would not constitute “a wise education” until subjects such as art, drama, elocution, music, singing, sport, and woodwork were incorporated into professional courses. Thomas maintained that a “cultural education” was as valuable to a tradesperson as a physician or lawyer. By “cultural” he meant those studies which developed “the emotional and spiritual side of a boy’s life”, encouraging intellectual curiosity, breadth of view and a “store of knowledge.”

Thomas was careful not to offend the supporters of public examinations, but he did point to their limiting effect on boys’ education. Having concluded in 1922 that “examinations have much too prominent [a] place” in schooling and that “too much stress is placed on the written examination”, he reminded his school community that what counted as legitimate knowledge was determined by the University of New Zealand and Department of Education. They were external examining bodies based in the capital city, Wellington. Thomas sought more freedom to devise courses of study that would suit every boy who attended the school. In 1929 he declared that “a boy at school could take the subjects for which he shows some talent and which would give him a more cultured outlook on life.” Thomas also wanted to see accrediting introduced for the University Matriculation (Form 5) examination, so that high school principals and not university staff would assess students’ abilities.

What Thomas was emphasising was the desirability of turning Timaru Boys’ High School into a multilateral or comprehensive institution. A range of courses should be devised to suit pupils’ different interests, their academic and/or practical strengths, and their vocational goals. In 1929 he argued: “The wider we extend our syllabus the more comprehensive the school becomes.” In the midst of a prolonged depression (1921-1935) however, Thomas understood that patience was required before such objective could be realised. In the meantime he needed to make the school an attractive place to ensure its long-term survival. Neither he nor his staff could afford to play down pupils’ performances in high status examinations. The school’s reputation depended on these.

The Thomas Committee Report

From the late 1920s Thomas was known among educators nationally for favouring a separation between the Matriculation examination and other, less prestigious, secondary school examinations. His reasoning was that candidates for the former should be those who, if successful, would proceed to the University of New Zealand for further study rather than entering “other walks of life”. He supported the introduction of a lower-status “school leaving certificate” for those who would enter the paid workforce upon leaving high school.

A Form 5 (Year 11) School Certificate was introduced throughout New Zealand in 1934. Controlled by the

![The Labour government of New Zealand that would commission the Thomas Report. In 1935 Rex Mason was not yet Minister of Education [back row, 4th from left]. The future Prime Minister, Fraser is 2nd from left, front row. Photograph taken by A W Schaef. Gustafson, Barry. Ref: PAColl-3222-3-002. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22641171](https://dehanz.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/NZ-Labour-Govt-1935-e1454988391687.jpg)

The Labour government of New Zealand that would commission the Thomas Report. In 1935 Rex Mason was not yet Minister of Education [back row, 4th from left]. The future Prime Minister, Fraser is 2nd from left, front row. Photograph taken by A W Schaef. Gustafson, Barry. Ref: PAColl-3222-3-002. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22641171

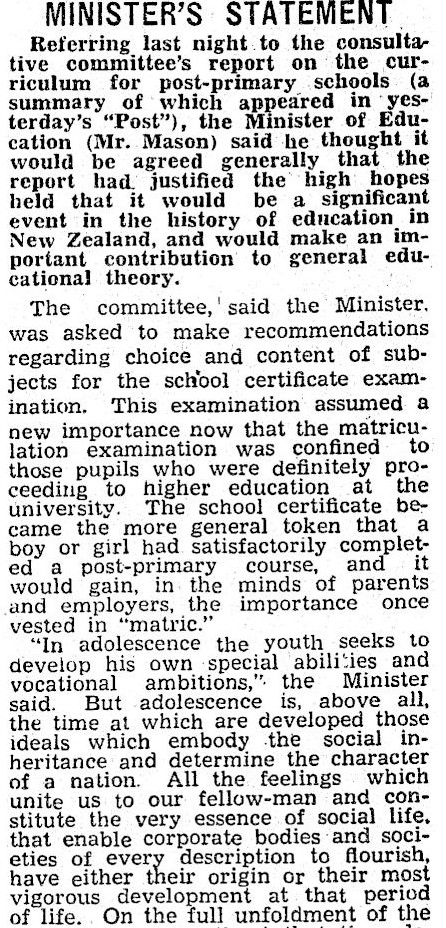

Thomas’ reforming views were given expression in 1942 when Dr Beeby, Director of Education, recommended Thomas to the Labour government’s Minister of Education as the ideal person to chair a consultative committee on the New Zealand post-primary school curriculum. The government had been informed by the University of New Zealand already that the present Form 5 (Year 11) Matriculation Examination was to be moved to Form 6 in 1944 and that the renamed qualification (the University Entrance Examination) could be accredited from 1944. Beeby correctly envisaged that these changes would significantly affect post-primary schooling. He advised the Minister, Rex Mason, accordingly.

Thomas was appointed chairperson rather than Frank Milner because, in Beeby’s opinion, the former was a better listener, more of a “liberal in education”. He would be more likely to entertain free and critical discussion of a variety of difficult post-primary education issues. Several scholars have concluded that Beeby’s judgment was vindicated. Thomas had a better understanding of the technical high schools than Milner. He was thought of as less didactic and not as forceful in his personality. His biographer, George Guy, described Thomas as having “tremendous energy”, “sincerity of purpose”, a “strong character”, “a quiet convincing manner”, with a keen sense of humour. He had a keen eye for detail. His philosophy of education was seen as being closer to that of the Labour government’s prime minister, Fraser, its minister of education, Mason, as well as the director, Beeby. They believed that Thomas was more committed than Milner to a genuinely more democratic model of schooling.

The Report noticed in the Evening Post, 11 February 1944

Thomas had the advantage of having worked with Beeby on the influential study, Entrance to the University (1939). Work on this confirmed for him the benefits of broadening post-primary curricula to suit a heterogeneous adolescent population as they moved on from the nation’s primary schools. The report had recommended that the School Certificate and University Entrance examination be separated by one year, and that students be prepared more thoroughly in post-primary schools for entering the University of New Zealand. All this pointed to Thomas as the ideal candidate for committee chairperson.

The Thomas Committee met from November 1942 until November 1943. Throughout, Thomas demonstrated to the Committee’s members his many talents and attributes. The Report, drafted by Arnold Campbell and Crawford Somerset as joint secretaries, echoed modern education thinking in the post-primary schooling domain.

That the Report’s authors emphasised the merits of curricular and examination reform was not surprising given the criticism expressed through the 1930s about the academic orientation of secondary schools. The Report captured the mood of liberally minded politicians during the war years (1939-1945) as they promoted a wide variety of social reforms to be introduced into New Zealand. They declared that students ought to be “willing to serve social ends and to lose themselves in social purposes greater than themselves.” The Committee’s deliberations were informed by the need to devise a curriculum and school leaving certificate that would prepare any post-primary student “for an active place in our New Zealand society as worker, neighbour, homemaker, and citizen.”

Historians generally agree that Thomas’ skilful chairing of the Committee, along with his well-known advocacy of curricular and examination reforms, enabled members to work collaboratively and effectively towards crafting a new post-primary curriculum through which students’ “varying abilities” and “occupational ambitions” would not be overlooked. Each adolescent boy and girl would “receive a generous and well balanced education.” These principles would apply irrespective of the type of post-primary school a student attended, whether technical, district high, secondary, combined secondary and technical or registered private secondary. The Committee identified subjects that they believed constituted a broad and balanced core curriculum for Form 3 to 5 students (English, social studies, general science, elementary mathematics, physical education, music, art, or craft), a curriculum that was to apply equally to New Zealand’s three kinds of post-primary institutions. Syllabuses were outlined for each of the subjects. They included a caveat that “none of our more detailed recommendations are intended to be binding on any school.”

The committee understood that its report would be scrutinised carefully upon release. Committee members argued that although the New Zealand government “has the duty to insist on certain minimum requirements and to encourage progressive developments” any temptation to implement a hard-and-fast philosophy for school teachers and school authorities should be resisted. They argued for a curriculum that “any intelligent parent” might reasonably expect high school teachers to deliver to girls and boys, hence the advocacy of their core curriculum.

To help promote this curriculum Committee members chose to make its study a prerequisite for students sitting examinations in four or five subjects for the revised, Form 6 (Year 12), School Certificate. A proviso was added however, that space was to be reserved in every student’s program for “optional pursuits” (non-core activities and subjects). The Committee took great care in presenting their proposals. Campbell and Somerset noted the Committee’s expectation that some post-primary school personnel were likely to “take the easy road” (that is, will make but minor changes to curricula) while others will choose to “take the hard road”. The latter involved endeavouring to meet, “the real needs” of a heterogeneous student population: “Ultimately each school must work out its own salvation” (Thomas Report). The Committee knew that there would be a variety of responses to its proposals.

The educational legacy of the Thomas Committee

The Committee presented the Report to Rex Mason in November 1943. He had the document published in December because he wanted it to be “read with care and fully and freely discussed.” Neither he nor the Labour Government necessarily endorsed everything that was said by the Committee but there was little doubt that Mason was pleased with what the Committee had achieved.

The Report was published during World War II, when many male post-primary teachers were serving in the armed forces overseas. They would have found it difficult to study the report. Both the men and women who returned to teaching after the war were likely unfamiliar with the Committee’s educational philosophy and approach to school reform. This had consequences later in the 1940s, when the government introduced legislation to support the Thomas Committee’s proposals—in the form of The Education (Post-primary Instruction) Regulations in 1945. The government could not expect schools to implement ‘the Thomas curriculum’ as speedily as it might have wished.

The government agreed to a nine month period of public consultation for the Report. Thomas and Mason spoke at various public gatherings. Criticism was forthcoming from private school authorities, especially the Catholic, for having been excluded from representation on the Committee. I was alleged that Committee members lacked awareness of the contentious nature of some of their curriculum proposals (for example, the teaching of Biology and General Science without reference to God). Beeby acknowledged that he had failed to consider Catholic perspectives and apologised to the bishops soon after the report was published.

With the raising of the school leaving age to 15 years in 1944 and the introduction of the ‘Thomas curriculum’ from 1946, the post-primary schooling environment underwent significant change. School principals and teachers knew they had to become familiar with the document and the 1945 Regulations, while trying to accommodate the many more students who were progressing from a primary or intermediate school to a post-primary institution. Beeby and Mason did not expect every teacher and principal to implement the Thomas philosophy and curriculum within a year or two. Mason predicted that this process could take four to five years, perhaps longer for some.

The transformation of New Zealand secondary schools into more comprehensive institutions that offered a wider variety of courses to a less homogeneous student population, and provided a broad common core curriculum, took far longer than was envisaged. Despite teacher attendances at professional development courses on the core integrated subjects and aesthetic studies, the conservative attitudes of many could not be altered quickly. Nor were the new specialist facilities, rooms, and apparatus, required for teaching the new curriculum areas, always available. Department of Education officers were under pressure from 1946 to provide ongoing curriculum advice to a large number of post-primary school teachers.

Though implementation of the Thomas curriculum had its difficulties, both Beeby and Mason were convinced that New Zealand’s post-primary schooling system required reform. Although the Committee’s proposals were often regarded as radical, if not revolutionary, the reality is that they were both evolutionary and predictable. Thomas died on 25 August 1945, not living live to see the Report’s implementation.

The Committee’s legacy is usually seen as positive. More New Zealand adolescents post 1945 had access to what post-primary school teaching staff could offer to a young population. A larger number of youth would be candidates for a qualification (School Certificate) that was valued by employers, parents, and students by virtue of a prolonged stay at high school through the raised school leaving age. Aspects of William Thomas’ curriculum philosophy, and that of the Committee are evident in contemporary high schools, although it is debatable if the ‘balance’ between humanities/social science and science/technology studies that was advocated remains a significant component of the present day national curriculum. Recent government emphasis on STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) to the detriment of the humanities, for instance, appears to contradict a major element of the Thomas approach. Nevertheless, the Thomas Report and its legacy continue to provide ideas for consideration for contemporary policy makers in education.