The performance-based system, known colloquially as ‘payment-by-results’, whereby teachers’ remuneration was partly determined by the success of their pupils at prescribed examinations, was introduced into Victorian government-aided schools in early1864. Although criticised by many throughout its 40-year existence, the system was not finally abolished until 1906, following the recommendation of a Royal Commission on Education (Fink). Victoria was not the only Australian colony to introduce a scheme of performance-based payment for teachers (largely based on a British precedent), but it was the first to do so, and the last to abolish it. The negative effect of the scheme on educational provision and pedagogy was profound and long-lasting.

Context

The Board of Education, the body responsible for the administration of Victorian government-aided schools, formulated regulations in 1863, which included arrangements for the introduction of a new system of payment to teachers. It was proposed that henceforth teachers be paid on the basis of their pupils’ performance at examinations in a number of specified subjects; and was based on a British scheme formulated in mid 1861, following recommendations of a Royal Commission on Education (Newcastle Commission), which had criticised the instruction provided in grant-aided schools. The commissioners suggested that in order to ascertain whether the elements of knowledge had been thoroughly acquired by pupils, they should be subject to regular examination, and furthermore that the income of teachers should be made dependent, to a considerable extent, on the results of the examinations.

Payment-by-results in Britain

The British arrangement allowed for a singular government grant to be paid directly to each school, thus streamlining a more complicated arrangement whereby schools had received a number of different grants. Under the new system – the Revised Code – the grants were paid to school managers, who were then responsible for paying the teachers. The size of the grant was determined by the number of passes obtained by pupils at the examinations (two-thirds of the total), the number of pupils in attendance, and whether or not the school was conducted by a certificated teacher. This meant the payment made for examination results was the main component of the grant made to schools.

In Britain, the introduction of payment-by-results was an attempt to refine what was regarded as a costly and inefficient system of administration. One of the main proponents of the British scheme, Robert Lowe, Vice President of the Education Department, a member of parliament (and author of an important report on education in New South Wales in the 1840s), acknowledged that the aim of the proposed scheme was to introduce something that was either ‘efficient’ or ‘cheap’, and which would allow the employment of a ‘lower kind of teacher’. Following various protests, the implementation of the Revised Code was postponed, and a modified version, including an exemption for Scotland, was reintroduced in 1862.

Proposal to introduce payment-by-results in Victoria

When the Board of Education attempted to introduce a similar scheme in Victoria, it was met with resistance not only from teachers, but more significantly, from members of the government. Opposition to the introduction of a performance-based scheme was perhaps not surprising when the underlying principles pertaining to the provision of public education in the colony are considered. In England, government aid for education was only intended to benefit the children of the indigent poor – those whose parents were unable to provide for their own needs and who therefore required the assistance of the state. But in Victoria, publicly-funded schools were open to, and attended by the children of all classes. This was similar to the Scottish situation where, as in Victoria, public schooling was not limited to the working poor. Scotland had gained exemption from the British scheme in 1862 on the basis that the Revised Code was incompatible with its system of education.

Teesdale Primary School, students and teacher, subject to regime of payment by results, c. 1900. Courtesy, State Library of Victoria, H2013 248/11

The utilisation of the schools by a range of classes in Victoria meant that many parents expected schools to offer more than rudimentary education. This was particularly important to those who lived outside the main centres of population, as the public school was often the only educational institution available to parents unable to pay the cost of travel and boarding fees. When compared to British schools, Victorian schools were liberally financed by the government, and there was no suggestion that the proposal to introduce payment-by-results was viewed as a cost-cutting measure. In England expenditure on education fell in the first years of the scheme’s operation, whereas in Victoria expenditure rose.

When the Victorian government received the Board of Education’s regulations in 1863, which included a system of payment to teachers based on the performance of pupils, it refused to approve them, primarily on the grounds that teachers should be ensured an adequate income based on their level of classification. Under the previous boards of education, Victorian teachers had been classified (placed in a class) based on an assessment of their literary knowledge and teaching ability, and some of the most highly qualified received an additional bonus for having passed certain higher level examinations (honours). The Chief Secretary (Premier) therefore objected to the proposal whereby a teacher’s salary would largely be dependent on the ‘results’ payment, rather than their qualifications, and insisted that teachers were to be ensured ‘a just classification and an adequate income’.

Introduction of payment-by-results in Victoria

The regulations were subsequently revised, and under a modified scheme, Victorian teachers were to receive a fixed salary (based on their classification), plus a ‘bonus’ payment based on the examination results. This ‘bonus’ payment, on average, represented 20 per cent of a teacher’s salary, or 10 per cent of his or her total income when monies received from school fees were also included. The allocation of government grants was managed by the central Board of Education, and not by the local managers, as was the case in Britain.

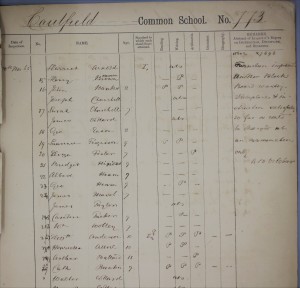

Recording the results from which payments were made. Victorian Public Record Office, Series 6359, Inspector’s Register Book, 1865. Caulfield Common School No. 773.

The Board of Education’s modified regulations, which included provision for the introduction of payment-by-results, received approval from the Victorian legislature, and were operative from 1 March 1864. The basic feature of the ‘results system’ was that a pupil in a government-aided school, aged seven years and above, was to be examined by a district inspector each half year in specified subjects, according to certain age-related standards. The six standards, ranging from ‘one’ (the lowest), to ‘six’ (the highest), specified what a child was supposed to have learned in each subject by a certain age. After undergoing two successive examinations at the one standard within a twelve-month period, a pupil was subsequently examined on the following two occasions at the next higher standard (irrespective of whether a pass had been obtained at the lower level), and so on.

Operation of the results system

Pupils were initially tested as to their attainment in reading, writing, and arithmetic (the 3Rs), and a payment of 2s (shillings) 8d (pence) awarded for a pass in each subject. In addition, pupils who had secured a pass in all three subjects, were then examined in grammar and geography, with a further 2s being awarded for each successful pass.

Student results recorded by the Inspector. Victorian Public Record Office, Ser. 6359, Inspector’s Register Book, 1865. Caulfield Common School No. 773

Therefore the maximum ‘payment’ that could be made per pupil, for each half year, amounted to 12s. The payment was made on the basis of the total number of passes gained by the school pupils as a whole, not on the number achieved by a particular class, and was then distributed according to seniority, i.e., a head teacher received a greater proportion than an assistant. But as the amount paid to each school was not to exceed £2 for every £1 raised from school fees and local contributions, if insufficient monies were raised at the local level, teachers were denied the full amount of their ‘results payment’.

In addition, payment was only provided for pupils who had met a minimum attendance requirement in the half year prior to the examination; if they had attended at least 100 days if they lived in a municipality, and 90 days elsewhere. But this was something over which teachers had no control (especially prior to the introduction of compulsory attendance in 1872), and attendance could be affected by illness, the weather, or various family needs. The requirement was considered an inducement for teachers to falsify attendance records, and although falsification was difficult to prove, if discovered, the penalty was severe.

Enquiries into the operation of payment-by-results, 1866-1901

First enquiry: Higinbotham Commission, 1866-7

In 1867, a Royal Commission on Education (Higinbotham Commission), reported on the operation of the results system in Victoria. Those in favour of the scheme claimed that children were better taught than formerly; pupils attended more regularly; teachers worked harder; organisation had improved; and pupils received a more uniform level of tuition.

Those who were critical–and it was acknowledged that the majority of teachers opposed the system–were concerned about the effect it had on educational provision and identified inherent flaws in the scheme’s operation. It was asserted that the system impacted negatively on the intellectual development of the pupils, as teachers restricted the curriculum to the subjects that would be examined, and only taught these to the minimum level required. The teaching of the higher branches (see Glossary) was discouraged, thereby depriving the pupils of a more liberal education. Also cramming and rote learning were common and teachers concentrated on the scholars whose performance would yield results.

Opponents also claimed that the tone and discipline of the school were overlooked; inspectors had little time to help and advise teachers; and teachers were required to undertake an undue amount of clerical labour in compiling the returns which were required to be sworn before a justice of the peace monthly and half-yearly.

Teachers objected strongly to what appeared to be the underlying assumption of the scheme: that they required external monitoring and needed a monetary incentive in order for them to perform their duties properly. Yet the fundamental premise that pupil performance was dependent on a teacher’s exertions and therefore was a reward for effort, had a serious flaw: the ‘results’ payment received by a teacher was not based on the number of passes achieved by his or her pupils, but on the number of passes secured by the school as a whole–and this was then distributed according to seniority.

Modifications made to the results system

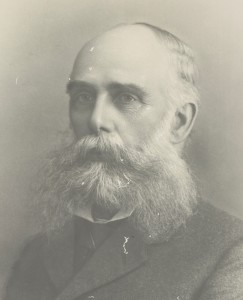

Inspector J. Dennant , c. 1905, one of the many who inspected schools to implement the payment-by-results regime. Courtesy State Library of Victoria, H36648.

Following the recommendations of the Higinbotham Commission, some minor modifications were made to the operation of the system of payment-by-results: the number of examinations was reduced to one per year, and inspectors made a second visit to report on the general organisation of the school; and the minimum attendance requirement was abolished from 1869. Henceforth a child who had attended during the previous five weeks could be examined. But these changes dealt only with the operation of the scheme, and the more fundamental concerns over pedagogy and the professional status of teachers, were not addressed.

Second enquiry: Rogers-Templeton Commission, 1882-4

In its final report, a subsequent royal commission on education (Rogers-Templeton) identified several defects in the results system, which it considered had had injurious effects on teachers and pupils. It recommended that

- a smaller proportion of a teacher’s income (15%) should depend upon the results.

- the method of examination should be changed ‘to give more weight to general intelligence and less weight to mere mechanical accuracy’.

- a distinct allowance be made in respect to the moral tone and general organisation of the school.

- an allowance be made for absentees if an inspector considered there was a satisfactory cause, and

- the age test should be modified.

Although evidence again suggested that the results system lowered the standard of education and ‘there could be no doubt’ that the present method had ‘an injurious effect on both teachers and taught’, the suggested changes were aimed at remedying defects in the operation of the system, rather than addressing its underlying principles.

Added to the report was a memo by Commissioner Templeton, a former teacher, recommending the abolition of the scheme, which he described as having an injurious effect on teachers and pupils, and which sublimated the ‘true interests of education’ to the passing of examinations.

Modifications made to the results system

The main modification made in response to the Rogers-Templeton enquiry was that in 1885 the course of instruction was revised and extended, and from 1889 the examination was based on the program of instruction: what the child had been taught that year. Then, in 1890, a merit grant of 15 per cent was awarded for discipline, organisation, and the general progress of pupils (reduced to 10 per cent in 1892).

Third enquiry: Fink Commission, 1899-1901

A royal commission established to enquire into technical education, the Fink Commission, extended its brief to investigate primary education. Its evaluation of the system of payment-by-results was damning and strongly recommended that the scheme be abolished as it had an adverse effect on teachers, inspectors, and pupils.

Various detrimental aspects of the scheme were listed:

- dull children were forced and bright children kept at a standstill,

- cramming was encouraged,

- emphasis was placed on factual knowledge rather than mental development,

- teaching was narrow rather than liberal,

- inspection was mechanical and relied largely on written tests which were inapplicable to many subjects,

- teachers were often paid for the results of the work of other teachers,

- teachers often suffered through causes beyond their control, and,

- proper recognition could not be given to the work of teachers while the system operated.

But as well as condemning the negative outcomes of the results system, the commissioners highlighted its fundamental purpose, which they considered made it untenable: the control of teachers. The underlying premise of the performance-based scheme was that teachers were untrustworthy and therefore needed to be subject to a form of surveillance. If they received fixed salaries, teachers would have a careless or indifferent attitude to their work.

A disturbing aspect of this focus on teachers, was that little thought had been given to the education of the children, or to the psychological impact of the examination system on their well-being. The child was looked upon as a secondary matter ‘deserving little or no consideration’. The emphasis on uniformity of achievement – a minimum standard – meant that the less able and backward children were forced to learn in such a manner that their school life was unattractive and they were unhappy; while the more able were not intellectually challenged and ‘kept at a standstill’.

Ending payment-by-results

The recommendation for the abolition of the result system was accepted, and the system was largely discontinued by 1902. But before the scheme could be fully abandoned, it was necessary to change the legislation relating to the payment of teachers, as the current Education Act specified the percentage of salaries paid for results. After a Teachers Act was passed in 1905, the scheme was finally abolished from 1 January 1906. By this time Victoria was the only place in the English-speaking world where the result system still operated.

Contemporary situation

Since 2008, Victorian students in years 3, 5, 7, and 9, together with students throughout Australia, have been required to sit annual examinations in reading, writing, language, and numeracy. The National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN), is designed to assess whether students are performing above, at, or below the National Minimum Standard in each area.

Although the salaries of teachers are not tied directly to the success of their pupils in these examinations, the results have been used as indicators of school achievement. Test results data are published on the MySchool website, allowing comparison to be made on the results achieved by each school.

Various criticisms, particularly by educationists, have been made of NAPLAN, some of which are similar to those directed at the earlier system of payment-by-results:

- it is not a true measure of school performance,

- there is pressure to ‘teach to the test’,

- there is a focus on test scores rather than on student learning,

- it has a negative impact on the well-being of students and teachers,

- it discourages collegiate behaviour among teachers,

- important aspects of learning cannot be assessed by a written test, and,

- the time gap between the test (May) and the provision of results (October) means it cannot be used as a diagnostic tool.

Performance-related payment

In September 2013, the British Education Secretary, Michael Gove, introduced a scheme (Performance Related Pay), which he claimed would improve the quality of teaching, helping schools find the ‘right teachers’. It aimed to end the existing arrangements, whereby salary increases were based on length of service, and henceforth, allow principals to determine teachers’ level of salary based on perceived performance.

In 2012, an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development investigation (OECD report) into whether performance-based pay improved teaching, found that overall there was no relationship between average student performance in a given country and whether or not it had a performance-based pay scheme. It reported that it was difficult to assess the impact on a student by a particular teacher, and that overall empirical analyses of the effects of PRP were inconclusive and difficult to assess. But what it did find was that:

countries that have succeeded in making teaching an attractive profession have often done so not just through pay, but by raising the status of teaching, offering real career prospects, and giving teachers responsibility as professionals and leaders of reform. (OECD, 2012, p. 4)

In Australia, the federal government’s 2016 budget proposed additional funding for schools from 2018, but stressed that this increase would be ‘tied to evidence-based initiatives’ that improve student performance. The OECD report suggests that no such evidence can be produced, as was the conclusion of the Fink Commission over 100 years earlier.