The first two decades of the century witnessed widespread reform in educational policy and practice in the Australian states, a period often described by contemporaries and later historians as an “educational renaissance”. Primary school education for all children became accepted and expected throughout society and systems of post-primary education were established and growing. But what happened to education in the 1920s and 1930s? Overall, this was a period in which a continued interest in reform and innovation in school education was seriously constrained by conservative forces, with promising developments late in the period interrupted by the Second World War.

In New South Wales, Director of Education Peter Board, with his great interest in New Education and the directions it promised for the post war era, was replaced by S.H. Smith. According to historians, Smith was an administrator and not an innovator. He led a push for greater efficiency in the basic subjects of reading, writing and arithmetic, in a reactionary period.

In all states, primary school education in the 1920s concluded with a qualifying examination, which would determine placement in post-primary education. Despite the reforms inspired by New Education in the previous two decades, this meant that primary school teachers taught for the examination and this discouraged experimentation. In secondary schools, final examinations also wielded influence on pedagogy. When economic depression hit Australia in the late 1920s and early 1930s, expenditure on education was cut drastically. New building was suspended and maintenance of existing buildings and equipment stalled. With cuts in staffing, classes in most schools were larger and operated without supplies of physical materials such as exercise books. Even when the worst of the Depression had passed, classes remained large, and building and maintenance lagged well behind what was needed.

However, the interwar period was not one of complete stagnation. There remained educators who advocated and agitated, formed associations, and introduced progressive practices in schools. In his study of primary school education in England between the wars, educational historian Richard Selleck described the enthusiasm of those who advocated what was now widely known as “progressive education”. Those reformers believed that the old ways were neither natural nor inevitable, and that great issues were at stake. They believed in a better world, free of world conflict such as that which had occurred in 1914-1918. That world would be influenced by citizens of the future.

Progressive Methodologies

In Australia, new progressive methods of teaching and learning were trialled in some schools, both state and private. Considerable interest in Montessori education had developed since 1913 and made a lasting impact on state educational systems for the teaching of very young children. Other progressive schemes were trialled with varying success and longevity. These included the Dalton Plan, the Gary Plan and the Project Method. The Dalton Plan, very influential in the United States and England, allowed pupils to spend considerable time on carefully devised individual assignments, giving them freedom to pursue their work according to interest and capability. The Plan was introduced in many Australian schools, although usually in modified form. In state schools, however, unless the new schemes were given official sanction, it was difficult for teachers to develop and sustain innovations, particularly when they were transferred from school to school.

Progressive Schools

A number of experimental or progressive schools, established outside the Departments of Education, aimed to put progressive theory into practice. (See Note 1 below.)

Morven Garden and Glen Carron, New South Wales

In New South Wales, the Theosophical Society put its educational vision into practice at Morven Garden School in North Sydney from 1918 to 1923. When this school closed, the co-principals continued a private progressive school, Glen Carron, at Mosman from 1924 to 1934. Coeducational, and catering for children of all ages, the school soon had 100 pupils. Blending theosophical ideas with progressive education, the schools featured Montessori education for younger pupils, small classes, minimal competition, no corporal punishment, a stress on service and citizenship, outdoor classes and activities, and sex education.

Turramurra College, New South Wales

Turramurra College, a private school for boys in Sydney’s north, operated from 1921 to 1928. Its founders were influenced by the progressive idea of the English educationist Homer Lane, and their school stressed a combination of academic work, self-expression and self-government. They introduced the Dalton Plan and a focus on literary self-expression in writing and performance. Art, crafts, music and manual work featured. This school closed when numbers dwindled, partly due to the opening of nearby Knox Grammar.

Frensham School, New South Wales

A boarding school for girls at Mittagong, New South Wales, Frensham was established in 1913 by Winifred West, a critic of conventional education who was eager to implement her own ideas. Frensham was soon known to be unusual, with non-denominational religion, few rules, no competition, marks or prizes. Music, art, and drama were important, as well as the academic subjects and sport. This school survived and operates today.

Presbyterian Ladies College, Croydon, New South Wales

Presbyterian Ladies College at Croydon entered an innovative period in the 1920s under the leadership of headmaster Neil McQueen. He introduced the Dalton Plan and the Project Method along with a regrouping of traditional subjects. Music and drama occupied an important place and discussion of contemporary events, including the work of the League of Nations, was encouraged. McQueen, however, was dismissed in 1930 by an uneasy school council.

Quest Haven, New South Wales

Also in New South Wales, Quest Haven was a small venture opened on a large property by the sea at Mona Vale in 1935. Originally this school provided for emotionally disturbed children, the patients of psychologist and teacher Mary Sheridan, but soon opened to a wider population. Claimed to be Sydney’s first truly progressive school, Quest Haven provided freedom for the children to follow their own interests, with a very elastic timetable. Outdoor lessons, exploration and play featured, as did arts, crafts, and puppetry. This school closed in 1940, perhaps due to war-time pressures.

St Andrew’s College and Preshil, Victoria

In Victoria, John Lawton, a former Presbyterian minister and a pacifist, established St Andrew’s College at Kew. At Lawton’s co-educational school, social responsibility was strongly emphasised as were creative and self-expressive activities, dramatic performances, debating and the teaching of Esperanto. Esperanto was an artificial language devised as an international medium of communication that was popular amongst progressive educators for its promise of world co-operation and peace. Self-government by pupils was encouraged, with a school council that had wide powers. Margaret Lyttle, a student of the Montessori Method, directed the junior school. When St Andrew’s closed in the early 1930s, Lyttle opened a small school run on progressive principles. This school, Preshil, increased in numbers and continued after her death in 1946 when her niece became Principal. In 1973, Preshil opened a secondary department. Preshil continues to operate in Kew, Melbourne to the present day, claiming to be “the oldest progressive school in Australia”.

Koornong, Victoria

Another notable example of a progressive school was Koornong which operated in Warrandyte, a village then beyond the Melbourne suburbs, from 1939 to 1946. Much planning went into this purpose built school on the part of its founders, J. Clive Nield and his wife, Janet Nield. The school was intended for 250 pupils: both day pupils and boarders. However, those numbers never eventuated, and the school suffered financial burden due to war-time restrictions. While it operated, it featured pupil involvement in governing the school, arts and crafts alongside academic subjects, and small group teaching.

Progressive Educational Leaders

In the new teachers’ colleges and university departments, a growing number of leaders and lecturers with postgraduate qualifications from the United Kingdom or the United States published substantial analyses of education in Australia, and books about theory and practice. Prominent educationists who published in this way, promoted progressive education and influenced student teachers and teachers.

They included Alexander Mackie and Percival Cole at Sydney Teachers College, G.S. Browne at Melbourne Teachers College and K.S. Cunningham, chief executive officer of the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER). The writing, work, and promotion of progressive theory and practice of each of these educationists was extensive and, in the long run, extremely influential. They were involved in the early formation of New Education Fellowship groups, the organisation of the New Education Fellowship Conference and the subsequent work of the NEF in Australia.

While student teachers were undoubtedly exposed to progressive educational theory and practice at college, their teaching experience was all too often discouraging. How many were as disillusioned as young Jessica Daunt, one of the fictitious teachers who features in Kylie Tennant’s first published novel, Tiburon, set in country New South Wales during the Depression? Jessica had kalsomined the small school room, put up pictures, painted the desks, made a sand-tray, and planted a garden. But she wanted more: “She wanted plasticine and basket-work, reading-books and a piano … She wanted drawing material and chalks and crayons and more pencils. She was tired of buying paint and nails, friezes and vases and kalsomine out of her infinitesimal salary” (Tennant, 1989 (1935), 110-11). Jessica didn’t return to Tiburon after the Christmas holidays.

The New Education Fellowship in Australia

The New Education Fellowship was formally established at a Conference in France in 1921 as an international body that would hold regular conferences and issue journals to exchange and disseminate information worldwide. It adopted a progressive agenda, where the needs of the child took primacy. Aims and objectives were to promote social education, education that met diverse intellectual and emotional needs, that afforded active self-expression, self-discipline, and collaboration, and that fostered the creation of world citizens. The Fellowship grew rapidly, holding biennial conferences that brought together educators from all over the world. By 1936 the New Education Fellowship comprised 52 national sections and groups and included renowned educators and authors, psychologists and philosophers in addition to teachers and interested public.

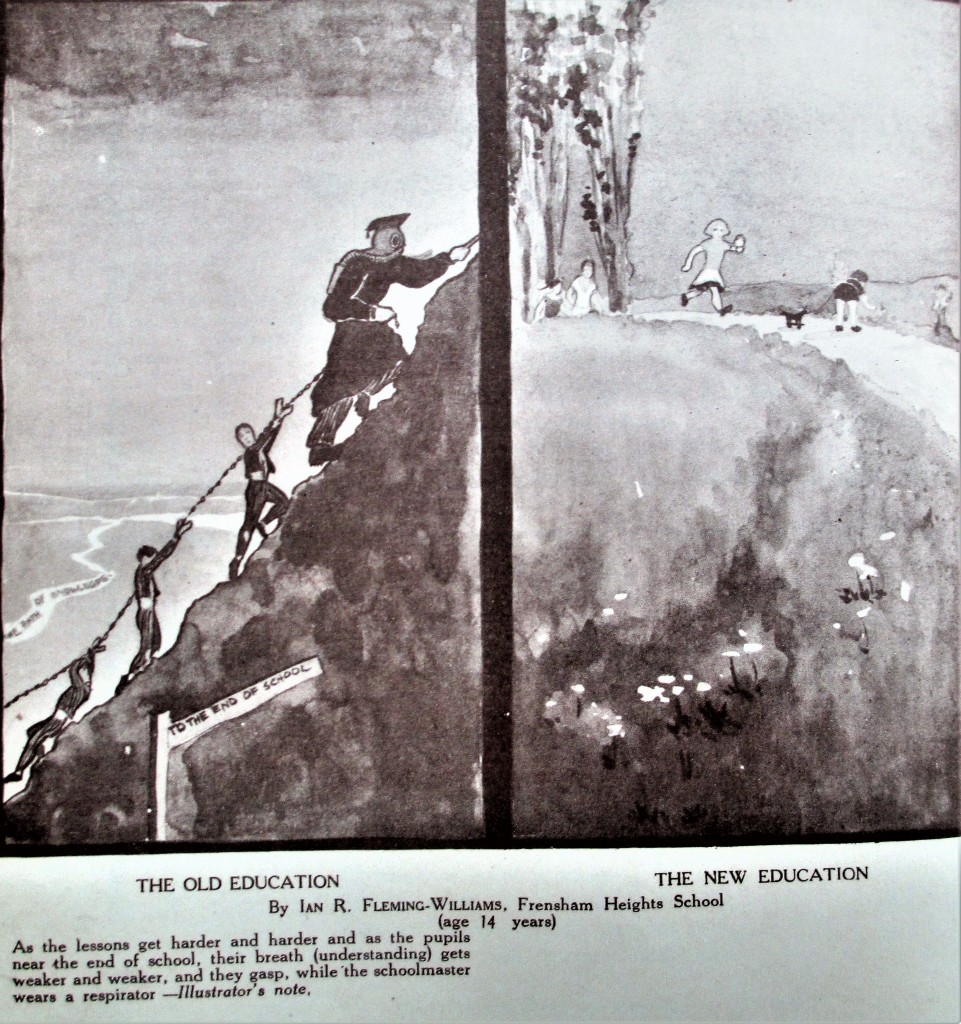

The old and the new, as depicted by an English pupil in New Era, journal of the New Education Fellowship. Source: New Era, July 1929

In Australia, some teachers and others were aware of the New Education Fellowship very early in its existence. In New South Wales, teacher Mary Lamond formed a Sydney group in 1925. Alexander Mackie was President and Lamond was Secretary. The group held lectures at Fraser House, the Teachers Federation headquarters in Bridge Street. The first lecture on 12 June 1925 was given by F.K. Barton, headmaster of the innovative Turramurra College. Attending were teachers from both public and private schools. Groups also formed in other states. One Sydney teacher, Miss Newton Russell from Paddington Infants School, attended the NEF conference in Denmark in 1929 while three Australians, including Mary Lamond, attended the 1932 Conference at Nice in France. In 1934, Ken Cunningham attended the regional conference in South Africa. On behalf of ACER, he invited the NEF to hold a conference in Australia in 1937.

The Conference travelled to each Australian capital city during August and September 1937. Several days of lectures and associated activities in each location were attended by thousands of teachers, lecturers, and others interested in the potential of education and the need for its reform. After the Conference, new, larger and more active NEF sections were formed in each state, joining with teachers’ organisations, parent bodies, and others in a concerted push for reform. Despite the coming of the Second World War, the momentum survived to have significant influence on the mainstream education of children in future decades.

Note 1: The work of R. C. Peterson in a series of papers, “Australian Progressive Schools”, Australian Journal of Education, Vol. 13-14 (October 1969-October 1970), is particularly relevant.