In late 1845, the minister and two deacons from the Collins Street Baptist Church in Melbourne sent a memorial to the superintendent of the Port Phillip District, Charles La Trobe, seeking permission to establish a day school for Indigenous children in the vicinity of the town. They proposed that the school be held in a four-roomed building, formerly occupied by Dr Macarthur, which stood on crown land situated at the confluence of the Yarra River and Merri Creek. Edward Peacock, who for some months had conducted a sabbath (Sunday) school in the area, was recommended for the position of schoolmaster.

Merri Creek near Dight’s Falls. 1865. Artist: Henry Gritten. State Library of Victoria [SLV].

Deciding to establish a school

La Trobe sought Thomas’s advice before responding to the application from the Baptist group. The Assistant Protector did not favour the proposal. His main concern was the perceived impossibility of conducting a school for Indigenous children at a fixed location, as many ‘hindrances’ would need to be addressed before the Aborigines would agree to remain in the one place, and cited his earlier unsuccessful attempts to conduct schools at Narre Narre Warren and Merri Creek. Thomas suggested that the only way to ensure continuous schooling would be to provide a van with supplies that could move as the people moved – something he considered undesirable.

William Thomas, c1860, some time after the school closed. SLV.

Thomas also queried the validity of some of the assertions made in the memorial, although he tactfully suggested that the ‘pious gentlemen’ had been ‘misled’, rather than that they were either uninformed or untruthful. He questioned how many children had attended Peacock’s sabbath school, suggesting that the number reported actually exceeded the number of children belonging to the Wurundjeri-willam group, and described the estimated enrolment for the proposed school as ‘fallacious’. Finally, Thomas provided a negative assessment of Peacock, with whom he had been associated in several educational ventures.

Some years earlier, Peacock had been employed by Thomas to teach at the Narre Narre Warren mission school but the relationship had soured after the schoolmaster made claims to others that the children had been ill-fed, and that this had negatively affected his success as a teacher. More recently, Peacock had used the assistant protector’s quarters to conduct his sabbath school, but had been evicted after the premises had been left in a ‘beastly state’.

Despite Thomas’s objections, La Trobe sanctioned the establishment of the school, granted the use of the land and building, and authorised a grant of £50 – to be provided in the form of rations.

The Aboriginal Protectorate: The civilising and Christianising mission

G. A. Robinson, the Chief Protector of Aborigines in Victoria. c1872. Photo: T.F. Chuck. SLV.

William Thomas, a Wesleyan and former schoolmaster, was one of four men appointed to the position of Assistant Protector of the Aborigines in the Port Phillip District [PPD]. The Aboriginal Protectorate had been established in 1838 by the British Colonial Office in response to a recommendation made by a parliamentary select committee that had examined the conditions experienced by ‘aboriginal tribes’ in British overseas settlements. In addition to the four assistant protectors, each of whom was assigned to a specific geographical area within the PPD, a chief protector (George Robinson), formerly ‘conciliator’ to the Aborigines in Van Diemen’s Land, was placed in charge of the overall administration.

Thomas had responsibility for the Melbourne-Westernport district; land occupied by Woiwurrung (Yarra) and Boonwurrung (coastal Port Phillip and Westernport) peoples of the Kulin nation, and which included the Merri Creek area and the township of Melbourne. The protectors, as the name suggests, had the task of protecting the interests of the Indigenous peoples. Their duties, as specified by the Secretary of State for the Colonies in correspondence with Governor Gipps, included: moving with the Aborigines ‘until they can be induced to assume more settled habits of life’, and when ‘settled’, to encourage them in habits that would ‘conduce to their civilization and social improvement’. They were also to instruct them ‘with the elements of the Christian religion’ (Cannon, 1983). Therefore the protectors were charged with promoting the two frequently cited components of the British colonial enterprise in its dealings with the native inhabitants of occupied lands – civilising and Christianising.

The idea that Indigenous peoples needed to be civilised was pervasive in the rhetoric of the time, and the twin notions of ‘civilising’ and ‘Christianising’ formed what was often referred to as the ‘civilising mission’: the mission to be undertaken by British colonisers to improve the social and moral condition of the native inhabitants who were judged as inferior in their stage of development. Religious instruction would lead them to adopt ‘such truths as would be conducive to their moral and mental improvement’.

Education was widely regarded as a vital element in the civilising endeavour. In particular, the education of the children was ‘of primary importance’, as they were regarded as more receptive than their elders and therefore the best means of securing social and religious improvement. The Baptist minister, the Rev. John Ham, and the deacons, believed that the establishment of the school would allow them to conduct an ‘experiment’ to discover ‘if aborigines, when taken young from their tribe may be educated and civilised’. A necessary precursor to this was that the children needed to be removed from the influence of their parents and other members of the group.

Indigenous schooling

The proposed school at Merri Creek was not the first attempt to provide instruction to indigenous children in the PPD. Shortly after the settlement of Melbourne, the government had created the Yarra Village Mission, under the supervision of the Rev. George Langhorne, an Anglican missionary. A school for boys and girls began at the site in December 1836, and although at first successful, it closed within three years due to an erratic and dwindling enrolment. Similarly, the various schools conducted by the assistant protectors on their mission stations had also failed to attract a regular attendance of pupils and had ceased to operate, including those established by Thomas at Narre Narre Warren and Merri Creek.

The main difference between the earlier attempts to provide schooling and the institution proposed by the Baptist churchmen, was that their institution would be primarily financed by private subscriptions and donations (£300 – £350 each year), whereas the earlier schools had been funded by the government. This was considered a distinguishing positive factor by some.

Merri Creek School 1846-48

Billibellary: Influential Indigenous supporter of the new school. Portrait by William Thomas. SLV.

On the morning of the first of January 1846, 27 Indigenous boys and girls, aged between seven and fifteen, plus three older women, gathered with their teacher Edward Peacock, for the opening of the Merri Creek School (also known as the Yarra Aboriginal Mission). An important supporter of the school was the ngurungaeta (leader) of the Wurundjeri-willam group, Billibellary, who sent his two younger children as scholars.

The pupils found themselves in an unfamiliar and regulated environment. Not only were they required to wear European-style clothing, they were confined within a building for several hours each day. Their lessons were also conducted in a foreign language–English. Although Thomas had observed that the children ‘understood sufficient English’, this did not equate with verbal fluency, or a familiarity with the words that appeared in the prescribed texts. Thomas was aware of the difficulties faced by the pupils, as some years earlier, when establishing the school at Narre Warren, he had written to the Chief Protector, indicating that he was ‘anxious that the Native Language be retained’; suggesting that the two languages be ‘amalgamated’ – taught together. But there is no suggestion that this arrangement was contemplated at Merri Creek, nor is there any indication that Peacock was familiar with the language of his pupils.

The daily lessons were held in a room of the former Macarthur residence. The building also contained three additional apartments: a kitchen, a bedroom for the teachers, and a parlour. The kitchen, which doubled as a barrack for the boys, was described as ‘a long, low place, dirty, damp, and miserable’ (Edgar, 1865). Sleeping conditions for the boys were improved when a new schoolhouse, measuring 30’ by 12’, was erected on the site a few months later. The girls slept in the parlour if the weather was inclement, but otherwise spent the night in mia mias (temporary shelters made of bark, branches, leaves and grass), about a mile distant. From the outset, the children were largely separated from the daily influences of family and friends, who nevertheless remained nearby.

The school’s early early operation and success: curriculum and pedagogy

The Merri Creek School according to a news item in the Port Phillip Gazette & Settler’s Journal, 18 March 1846, p. 2

The pupils of both sexes were taught together by Peacock, perhaps with the assistance of his wife. Two sessions, each of 45 minutes, were held in the morning. Reading was accorded the highest importance, and pupils’ progress in the subject was frequently mentioned, often indicating the specific number of children who had attained particular levels of competence. For instance, in November 1846, it was reported that seven boys could ‘read the Testament without having to spell many of the words’, seven boys read in the ‘first class book’, and one was ‘learning the alphabet’. But this more detailed information about scholastic progress was provided for the male pupils only, and the girls were merely said to be ‘learning to read’.

Frequently the girls were described in disparaging terms – they were less intelligent, making less progress, ‘listless’, and even their appearance was deemed to be somewhat unfavourable. Thomas expressed doubt whether any success would come from encouraging females in the establishment, as they were taken away by men when aged ten to eleven, and there was no record of girls above that age attending the school.

Some information was provided on the method of teaching pupils to read: first they learnt the ‘alphabet’, then progressed to reading ‘syllables’, which involved breaking a word into separate parts before combining them to form the complete word. The method had been promulgated by Andrew Bell, who (together with Joseph Lancaster), was influential in determining the type of schooling provided for the children of the labouring classes (popular education) during the first half of the nineteenth century (Hurt, 1971). The limited scope of the curriculum at Merri Creek was similar to that thought suitable for the British lower classes.

Much emphasis, as indicated in the selection of the reading material – the bible, testaments, catechisms – was placed on religious (moral) instruction. The main provider of popular education in England, the National Society, claimed in the year that the Merri Creek school was established, that religion pervaded the whole teaching of the schools (Hurt, 1971).

One student was critical of Peacock’s teaching and the educational fare offered – ‘Him make little boys say a, b, c, sometimes. … Him preach …him preach all day, him preach PLA-A-ANTY’ (Edgar, 1865).

During the afternoon the pupils were engaged in recreation or in ‘useful employment’. For the boys, this meant cultivating vegetable gardens and growing crops. Eventually, four acres of wheat were under cultivation, two acres of potatoes, and the students maintained an extensive vegetable garden; the produce of which was sold at the Melbourne market. The development of agricultural skills was perceived as part of the ‘civilising’ process – helping indigenous youth adopt a new relationship to the land, and ceasing, as described by Thomas, their ‘erratic habits’.

There is no mention of the girls partaking in these activities. While the boys worked or played outside, the girls were developing various domestic skills, washing clothes, cleaning the house, ironing, and sewing.

Thomas Walker (n.d.), a boyhood friend of the boys, described how many evenings were spent fishing and killing opossums. He also recalled that the boys and girls swam in the river (at separate times) in the early morning and afternoon, and that they engaged in activities such as climbing, throwing the boomerang, running, jumping, and cricket.

Despite his initial opposition to the establishment of the school, and to the appointment of Peacock as master, Thomas reported favourably to Chief Protector Robinson in May 1846, saying that he ‘should not have supposed that so much could have been accomplished in the short space of time’. Later he observed that the pupils’ progress was equal to that of European children of the same class and that there was ‘no reason to doubt they are equally capable of receiving instruction’.

This positive assessment was shared by the Baptists, who after the school had been operating for three months, determined that the ‘experiment’ had not only been a success but had exceeded their most ‘sanguine expectations’. The pupils were capable, willing to learn, and had shown that they were ‘competent to receive and retain the information communicated to them’. To demonstrate this competence, on the seventh of May the children were taken to Melbourne, where they demonstrated their skills in reading and singing. The occasion was used to provide information about the institution and its achievements, in order to garner ongoing support, especially financial support.

Causes of the school’s decline

During the latter part of 1846, it was apparent that the school was in a troubled state. With the death of Billibellary in August, the school lost its ‘prime supporter’. But this was but one factor contributing to the school’s decline.

By July, the project was experiencing financial difficulties, and was £130-4-3 in debt. Subsequently the education committee sent a letter to the various protestant bodies seeking donations, but only received two responses. A letter published in a newspaper in October, indicated that there was now a prospect of abandoning the school due to a lack of funds. Eventually the funds were boosted by a government grant of £150 for the 1847 calendar year, but this was apparently insufficient, as in the following April the debt stood at £90.

Outside influences were also blamed for having a negative impact on the school. The main grievance was the accusation that some members of the Native Police force (Indigenous men, led by a European officer) were said to have enticed boys away from the school on a number of occasions. Although these accusations were refuted, and in each instance the pupils were brought back to the school by Thomas, Peacock, or their parents, it had an unsettling effect.

Of more serious concern was the negative attitude of the students. Thomas reported in December 1846 that the school was in an ‘unstable state’, and Peacock had complained of ‘disorderly conduct’. Later that month, Thomas met with members of the education committee to discuss the future of the school and to determine ‘upon a methodical plan of proceeding’. Despite earlier reports describing the pupils as ‘docile & tractable’, the behaviour of the male pupils was now considered to be ‘unruly’, and that a ‘few rules’ needed to be introduced ‘to bring the scholars under control’. The boys’ negative response when informed about these rules, demonstrated to Thomas ‘the obstinate, perverse characters the master had to contend with’.

The following year, some parents spoke to Thomas about their dissatisfaction with the school and with Peacock’s behaviour. They accused the schoolmaster of beating the children and complained that they were always at work. In response, Thomas upbraided them for their ‘ingratitude’ and insisted that their children were well taken care of, but acknowledged to Robinson that there was a ‘clamour against the school’. When the parents indicated that they might remove some of the pupils, Thomas although not sympathetic to their case, agreed to speak to the schoolmaster. Peacock, in turn, accused the girls of having been encouraged by some of the older women to steal, thereby suggesting they were of bad character – a response that failed to address any of the parental concerns.

Yet in November 1847, Thomas reported that the school was in a much improved state, and especially commended the cultivation of the gardens. But the situation deteriorated. By this time most of the Wurundjeri had left the area for various reasons, including an influenza outbreak. Then in the following month most of the wheat crop was destroyed by a fire lit by some schoolboys and others – whether deliberately or not is unclear. Following this incident, the boys left the school and for Thomas, this ‘deceptiveness’ removed the last shadow of hope of the school’s success, as ‘they or their parents seem bent on destroying the mission’.

Within a few days of Thomas sending a report in early December, the Wurundjeri had left the encampment and the school abandoned. Thomas encountered the group about 65km from Melbourne but could not induce any pupils to return. By February 1849, only five pupils remained, including two youths from Port Fairy who had been sent to the school following a court trial.

In January 1848, the deacons resolved to discontinue operations in connection with the school, and asked the government to assume responsibility. They desired, however, that it be distinctly understood ‘that they are not forced to the step, by any conviction, that the Aborigines of the country are incapable of mental or moral improvement’.

When Robinson visited the school in early May 1848, he found the garden and grounds neglected, and no regular system of instruction or industrial labour. Thomas subsequently reported to La Trobe that when he had gone to Merri Creek to obtain the record of daily attendance, no-one was there and had been told that Peacock and the boys were putting up a fence at New Town (Fitzroy) Subsequently he found that the stable and an uncompleted out-building had been removed. Peacock was accused of taking materials from the school, and his resignation was accepted several weeks later.

Merri Creek School 1848-1851

In early June 1848, Francis Edgar was appointed schoolmaster at Merri Creek. During its second phase the school differed in many ways from the first. There were fewer pupils. At first there were only three to five pupils, rising to eight in the latter part of 1849. All were male, and the youngest was eleven years of age. Another significant difference was that the pupils were ‘mainmeet’ (foreigners to the area), who had been sent there for various reasons by the Native Police or court authorities (Patton, 2006).

The pupils continued to study a limited range of subjects. Although little specific information was provided on their progress, Edgar’s daughter Lucy later recalled that the boys read ‘tolerably’ and could write in ‘large bold characters’ (Edgar, 1865). In October 1849, Thomas recorded that the youths were ‘advancing in their studies’ of reading and writing, and that the school continued to be conducted in ‘a steady preserving manner’ – bringing its ‘Aboriginal inmates into the paths of civilization’.

Attention continued to be given to agricultural and physical activities. Cereal crops, fruit, and vegetables were grown, and a variety of animals kept. An activity of some note was the construction of a wooden bridge across the Merri Creek, which was opened in a formal ceremony in June 1849. (It was washed away by severe floods the following year).

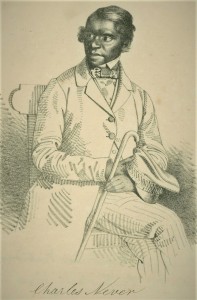

Charles Never, pupil of the school. c1851. Artist: William Strutt. SLV.

Despite favourable reports by Thomas and the committee, the pupils did not necessarily wish to remain at the school, and many attempted to leave – or according to Thomas, ‘abscond’. By the end of March 1850, only one pupil, Charles Never, remained. The following month, under an arrangement sanctioned by La Trobe, he was apprenticed to a tailor in Melbourne for twelve months.

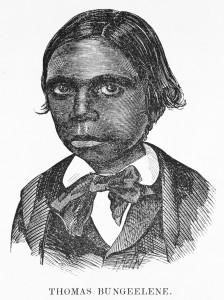

With Charles Never’s departure, the only Indigenous children at the residence, were two young boys (Wurrabool and Thommy Bungaleen), who with their mother (Yaungun), had been taken to live at the Yarra Mission in 1848, following the death of their father (Christie, 1994). When Yaungun left the mission in April 1850, Edgar sought permission from La Trobe to remain at Merri Creek for the next twelve months, during which time he offered to care for the children at his own expense. La Trobe agreed to this arrangement.

Thomas Bungeelene, one of the last pupils of the school. 1857. Engraving by George Slater. SLV

Outcomes

In terms of one of the stated aims of the school – to determine whether the Indigenous children were intellectually capable of learning – the ‘experiment’ was deemed a success. But in the wider context of providing ongoing educational instruction to Indigenous children, it was not successful.

In 1941, Edmund Foxcroft identified the errors of judgement that had become apparent with hindsight, stating that the lessons ‘of this experiment are clear enough now’. The mission had followed a similar course to that of Langhorne’s school (Melbourne Mission). For a time the natives were attracted; then after a few months or perhaps a year they resumed their natural ways of life (Foxcroft, 1941).

Lucy Edgar agreed that a ‘trial had been made but eventually it failed’. The pupils had a:

dislike of continual constraint, longing for their own country and old associations. Only half civilised, and not in any degree Christianised; being merely conformed to the ceremonies that were imposed upon them, without feeling any vital religious principle at work in their hearts. (Edgar,1865.)

Indigenous adults and children rejected the hubristic attempts made by Europeans to impose the ‘benefits’ of British culture, and indicated via various methods of resistance that they had little desire to become ‘civilised’ or ‘christianised’. Instead, they preferred to retain their own cultural and social mode of life, and in the early years of settlement were largely successful in achieving this aim. Eventually, methods of enforcement, including the long-term removal of children from their parents, further eroded Indigenous rights and preferences.