The best way of teaching reading and writing has been a contentious question for at least two centuries. Phonics first approaches, building reading skills from the progressive recognition of letters, syllables, words, phrases and sounds has a long history, as do meaning-centred approaches that attempt to contextualise words, phrases and sentences within accessible stories and other contexts. There is no consensus on the most effective approach as every learner is unique. Inevitably educators incorporate elements of each in their teaching of literacy.

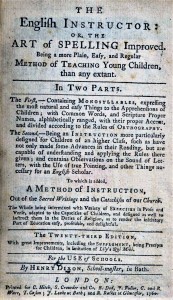

A very early text used for literacy teaching in Port Jackson. Dixon’s English Instructor (1760).

We have a brief indication of how the teaching of reading in the Native Institution near Sydney occurred in the early nineteenth century: Maria, age 13 could spell four syllables in the Bible and could read, while Wallis, Jimmy, Henry and Maria could repeat the alphabet. Mastery of the alphabet was the starting point, and from there, especially in the mainly protestant schools, Bible reading was the eventual aim. In the early nineteenth century there were other materials to support literacy learning, especially catechisms (compilations of religious truths), spelling books and even some materials graded for young learners. Dedicated children’s literature remained rare, as were books themselves early in the history of the Australian colonies.

As early as 1789 literacy teaching texts arrived in Port Jackson, specifically, 48 copies of Dixon’s The English Instructor. Spelling books rather than readers would play an important part in early literacy education.

Materials for writing, especially slates, became increasingly available from 1810. Monitorial schooling from the 1810s in New South Wales was founded on the belief that the literacy instruction of children should be graded according to children’s age and ability, and instructional materials were developed accordingly, by both Andrew Bell and Joseph Lancaster, the founders of monitorial schooling. In 1821 the master of successive government (publicly funded) schools was asked about books and reading materials available to students:

As the Public school was taught on the Lancastrian plan, only Bibles & Testaments were used; and on my removal to the orphan School, the Papers & cards that were used in the Public School I removed with me. (Thomas Bowden, 1821, quoted in Niall & Britain eds, 1997, p. 4).

Literacy instruction was usually attached to religious instruction, especially in those schools supervised by Church of England clergy as was usually the case where government subsidy occurred. It was generally thought that for the lower classes, often from convict or ex-convict families, that religiously oriented literacy education would assist the development of social order and control.

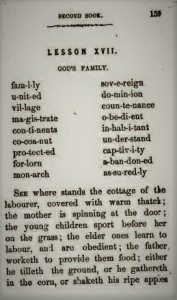

From an Irish National Reader. Word list and story.

Origins of the Irish National readers and other texts

There was urgency in Ireland from 1831 for the production of materials to be used in the new National schools. These were schools that were expected to enrol children from both Roman Catholic and protestant families, and if that were to occur, texts used in Roman Catholic and Church of Ireland (protestant) schools needed to be replaced. The new texts would be Christian in reference and moral teaching, but they would abjure the dogma of specific churches.

The texts produced were a great advance on what had been available previously. They included a range of different books covering grammar, arithmetic, poetry, geography, history and philosophy but the reading books, variably named over the years, including Books of Lessons, were the most popular, and were rapidly imported into the Australian colonies. The readers provided lessons in reading, suitable stories, poetry and other literary genres, but also spelling, dictation, vocabulary building, grammar and comprehension (Waugh, p. 53). They were the best school textbooks available in the British Empire. They were imported in great numbers into Upper Canada and New Zealand as well as the Australian colonies.

From the mid-1830s in the United States there were the popular McGuffey readers, but unlike the Irish National readers they had a much more assertive denominational, Presbyterian, Calvinist, message and tone.

The Irish National readers in the Australian colonies

There was no question that the new National Schools Board established in greater New South Wales in 1848 would use the Irish National readers. They appeared to meet the task brilliantly. They supported the non-denominational teaching of literacy, they provided graded texts that supported children’s growing skills in reading and writing; they were based on common Christianity principles, and they certainly supported the mission of the expanding British Empire and loyalty to the monarchy. Agents of the National School Board displayed the texts at the town meetings that were convened to petition the National Schools Board for the establishment of schools. After William Wilkins, principal of the Normal and Model School in Sydney was appointed, reflecting his English training, some English textbooks were introduced to the schools as well, but the Irish readers were barely challenged.

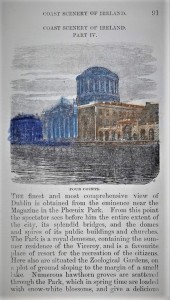

From an advanced Irish National Reader.

The Irish National Readers were used to educate generations of Australian children, being used especially in the 1840s, 1850s and 1860s. They were relatively cheap to buy. In some schools they were used into the 1880s, including many denominational schools. Following separation from New South Wales the Irish National texts dominated National schools’ education in Victoria. In both colonies, reading proficiency would often be expressed in terms of which of the Irish readers students were working through, from easiest, I, to the most difficult, V. Few students ever reached Reader V.

The stories and other texts in the Irish readers were designed to appeal to the interests and better instincts of children. They were a force for the moralisation of children and their reconciliation to their social class circumstances. There were anthropomorphised animal stories, popular Old Testament tales and much more including stories of village life (in Ireland for the most part). In the second book were lessons to be learnt from the life of Harry:

There was once a little boy whose name was Harry. He went to school every day and as he was a quick little fellow and loved his book, he soon got to the head of his class. But Harry had two sad faults; he was selfish, that is, he cared for himself more than for anyone else; and he was greedy, that is he was too fond of eating.

There was an expected approach to political economy that would not have impressed all its readers. From Book IV comes a justification of ‘trickle down’ economics:

the rich man therefore, though he appears to have so much larger a share allotted to him, does not really consume it but is only the channel through which it flows to others and it is by this means much better distributed than it could have been otherwise …

Good girls were invariably selfless; caring for others was usually their appreciated mission.

The Irish National Readers were mandated for Tasmania in 1854, children to be assessed on their progress through the appropriate reader. In South Australia, in 1860 a choice was given by the Board of Education. Schools could work either with the Irish National Readers or texts published by the British and Foreign School Society. In 1856 Governor Arthur Kennedy in Western Australia won the argument to base government-subsidised colonial schools on the Irish National system, with its common Christianity texts, a settlement that lasted to the early 1870s.

Suitable for the Australian colonies?

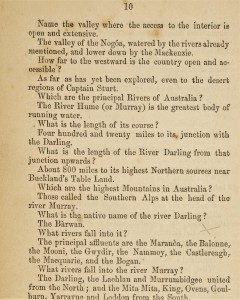

Mitchell’s Australian geography for schools, 1850.

Problems with the Irish National readers were identified quickly enough, apart from the expected criticisms of those who had no time for non-denominational common Christianity.

The readers were resolutely Irish, with virtually no reference to the geography of Australia and its history. One early attempt to write a geography text for colonial schools came to grief as the method the author used was the increasingly dated approach of the catechisms (see illustration). This was a text produced by Thomas Mitchell, Surveyor-General of New South Wales, for the Denominational Schools Board in 1850. It posed uninteresting questions, concentrating on the names of physical features such as capes, rivers, towns and mountains, with answers to be learnt by heart, and in language that was often too difficult for children.

Henry Lawson, Australia’s renowned writer of short stories gave his view of the Irish readers as he experienced them at school in the 1870s:

Our school books were published for use in the National Schools of Ireland, and the reading books dealt with Athlone and surrounding places, and little pauper boys and the lady at the great house. The geography said: ‘The inhabitants of New Holland are amongst the lowest and most degraded to be found on the surface of the earth.’ Also: ‘When you go out to play at 1 o’clock the sun will be in the south part of the sky.’… it was in the book. (Quoted in Niall & Britain eds, 1997, p.50.)

Much later, and coinciding with the transition of the National schools of New South Wales into public schools (1866), William Wilkins announced the compilation of a set of Australian School Books. They would be based on the Irish books “but will be specially adapted to Australian peculiarities” (Wilkins quoted in Turney, 1992, p. 143). They were published from 1869 and initially were well received. They became The Australian Class Books: A series of progressive reading books for schools and families. Nevertheless, through the 1870s other readers, some of them more attractive to children were published and available in the colonies, both from Australian and English sources.

By 1876, there was a revised Fourth Reading Book (Irish National Reader) for use in Australia and New Zealand. This edition was expected to meet the needs of colonial youth, including new topics written by “gentlemen of Colonial experience”. Australian and New Zealand exploration, discovery, and wildlife formed most of the new topics.

South Australia’s pioneering school magazine, Children’s Hour, 1889, but this edition 1916.

In 1889 The Children’s Hour was published by the South Australian Education Department. It was soon imitated in the other colonies. These magazines were regularly published, providing reading matter for children and their families in schools and at home. The stories, articles and poetry elevated Australian themes. They were the most radical of the local departures from the Irish National texts.

Nevertheless, readers produced by various publishers continued as a basic literacy instructional tool in primary schools into the second half of the twentieth century. From the late 1870s through to the 1890s there

Nelson’s Royal Readers were a popular successor to the Irish National Readers

were Nelson’s Royal Readers. They had cornered the school market with their attractive illustrations and sturdy bindings. The historian, Marjorie Theobald, discussed the political and social world that these school readers inhabited:

White protestant peoples were superior to all others.

They had caused the greatest of world empires, the British Empire.

Men were leaders, and women generally were more suited to domesticity.

The northern temperate zone was the workshop of the world and most civilised. (The heat of the tropics enfeebled white men.)

Britain was the epicentre of civilisation. The energy and achievements of British explorers, merchants, soldiers and more were quite remarkable.

(Theobald, 1996, pp. 200-201)

The Irishness and world view of the National readers had been displaced with a late nineteenth century set of racial, gendered and imperial discourses. Also, the texts of the new readers were more secular. This was certainly not the case in the materials produced for example, by the Marist and Christian Brothers and other orders for Catholic schools. An early nineteenth century tolerance by the Catholic Church for the Irish National readers and some of its successors had come to an end.

Significance of the Irish National readers

The Irish National readers and associated texts promised mid-nineteenth century colonial schools a solution to the vexed question of how to avoid fractious religious dissension in the development of government-assisted schools. More than this they supported modern approaches to literacy education. Graded exercises were sensitive to children’s interests and abilities, as well as a sense of what children should know and feel about Christianity. They were to support their moral development and secure their admiration of Great Britain and its influence in the world.

Criticisms of the readers as they developed in the colonies were less about their pedagogic principles than their Irishness. The movement towards responsible government in the colonies, the growing federation campaign, and a cultural shift recognising value in native flora and fauna, and the need for young people to know their Australian geography, all had a role to play in the replacement of the Irish readers.

Criticisms of the readers as they developed in the colonies were less about their pedagogic principles than their Irishness. The movement towards responsible government in the colonies, the growing federation campaign, and a cultural shift recognising value in native flora and fauna, and the need for young people to know their Australian geography, all had a role to play in the replacement of the Irish readers.

From the 1870s, religious problems became very significant once more. In Victoria the Education Act of 1870 promised a more genuinely secular curriculum for public schools. The Irish Readers were not secular at all. Biblical stories and Christian teaching were both prominent, even if based on common Christianity principles. In Victoria the Irish readers were officially replaced in public schools in 1877. The Irish National readers belonged to the circumstances of white colonisation in Australia, but they had a long-term effect. They pioneered the possibility of systems of non-denominational government (public) schooling and curricula that could be detached from religious dogma.

NOTES:

- The Irish National readers may be read on-line courtesy of several libraries. For example, the Fifth Book of lessons: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hn5xys&view=1up&seq=12

- Thanks to Robyn Ewing, Keith Moore and Tom O’Donoghue for assistance in composing this entry.