National schools were founded from 1848 in greater New South Wales. They were governed by a board established and funded by the colonial government. The curriculum of the National schools was utilitarian, based on ‘common Christianity’ principles [see Glossary]. They were expected to expand the access of families to schooling, especially in areas where private or denominational (church) schools were either absent or unsatisfactory. The Church of England and Roman Catholic bishops and clergy were usually hostile to National schools. They argued that education should be trusted solely to state-assisted denominational schools. The colonial state in eastern Australia funded such schools through a Denominational Schools Board. This dual approach to schools funding, National and denominational, continued through to the passing, mainly from the mid 1870s, of the so-called ‘free, compulsory and secular’ education acts.

With the separation of Victoria from New South Wales at the end of 1851, the few National schools operating in Victoria were handed over to a hastily established Victorian National Schools Board. It was to assume management of these schools and to organize the education of the significant numbers of children who had arrived on the Victorian goldfields with their parents. The Victorian National Schools Board signified the first effort of the Victorian colonial government to establish a state education system.

The Victorian Board needed to appoint an inspector and agent for the goldfields to promote the benefits of National education to miners and their families. Such families often appeared indifferent to the schooling of their children. The more immediate need was for children to assist their parents on the diggings. (Compulsory schooling was not legislated in Victoria until 1875.)

William Knowles Miller (1830-1861) was appointed as inspector and agent to represent the Board in negotiations with miners to erect temporary school accommodation. Miller was a crucial appointment. Van den Ende was not the only writer to advise on the importance of finding the right man to act as inspector: ‘Take care whom you choose for inspectors; they are a class of men who ought to be searched for with a lantern in one’s hand’ (see Ball 1963, p. 5). The lantern used to find Miller surely had a short wick or clouded lens. Miller would put self-interest above responsibility and fidelity.

National schools in the colony

With the impending separation of the colony of Victoria from New South Wales in 1851, the National Schools Board in Sydney was anxious for a similar body to be set up in Victoria. Monies held by the Sydney Board on account for schools in the Port Phillip District totalled £2,853.11.0. The chairman of the Sydney Board, John Plunkett, advised that his Board was prepared to hand over the funds to any authority constituted to receive it. The Victorian board was duly constituted. It was accommodated in a suite of three rooms in Lonsdale Street West, Melbourne, at a rental of £120 per year for a period of five years.

By its charter the Board was a non-denominational corporation set up to establish and control non-sectarian public schooling in local communities. Its inspectors would operate as statutory agents, explaining to communities how they could best establish a school. The Board was then to regulate the schools so that they guaranteed the basic principle: National education was Christian, but neither proselytizing nor promoting a particular denomination, that is, National schools were to be non-sectarian.

Advertisements were placed in the Argus and Herald newspapers seeking applicants for the

Benjamin Kane, first Secretary of the Victorian National Schools Board. State Library of Victoria.

position of secretary. Robert Fennel was initially appointed, but he withdrew. Subsequently the eighteen-year-old Benjamin Francis Kane was appointed from a list of sixteen applicants.

The appointment of a young Benjamin Kane was not unusual for the time. The discovery of gold in the colony left towns and suburbs bereft of responsible trades-folk, farmers, domestic servants, clerks, artisans and mechanics of every description. By March 1852 Governor La Trobe had raised the salaries of public servants as a measure to induce them to stay at their posts. Kane was one officer who benefitted from La Trobe’s policy.

With the great influx of people into the colony, the National Schools Board Commissioners were anxious to use the opportunity to extend the system of National education throughout the colony. The Commissioners resolved to appoint an ‘Inspector and Agent’ at an annual salary of £500.

Appointment of the first inspector and agent

In response to advertisements, twenty-seven lay applications were received, members of the clergy being excluded from eligibility. William Knowles Miller was appointed at the Board’s meeting on 26 July 1852 with the understanding that the Board could dispense with his services at any time. He was twenty-two years of age at appointment. Miller’s testimonials and credentials were impressive. He was educated at King’s College, London, the second son of Sergeant Miller of the English Bar. On leaving the College at the age of twenty, he studied and practised law at his father’s firm. Displeased with changes to the common law, which he believed had caused disruption in the profession, Miller resolved to try his fortune in the colonies and emigrated to Victoria.

In his application, Miller provided references from Justice Therry, Chief Justice of New South Wales, who stated that he had known Miller’s father ‘on very friendly and intimate terms’ and that Miller had worked for two and a half years in his father’s law firm. Another reference gave witness to Miller’s industry, attention to business, and faultless conduct. Miller’s application indicated that he had temporarily accepted the management of the common law business of Messrs Ross and Clarke, the Board’s solicitors. Nowhere was any reference made concerning teaching prowess or educational administrative ability.

Following appointment, Miller was to focus on setting up tent schools on the goldfields. This required him to collect contributions from miners to pay for the purchase of tents and to enlist the names of children expected to attend school under the auspices of the Board. He was dispatched to the goldfields with great haste. He was required to report to the Board at least once a week.

Schools on the goldfields

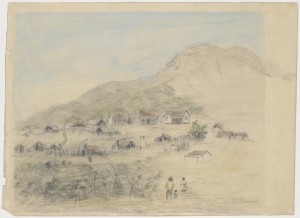

Rough sketch of goldfield in Victoria, mid 1850s. H28122, State Library of Victoria.

Miller’s reports indicated the difficulty of setting up schools on the goldfields. Tents were the preferred accommodation as they could be taken down at minimum expense and re-erected on the site of new diggings as the miners moved to the new locations. The effort to convince miners to send their children to school took considerable effort. Miners were loath to spend money for schools. As with most National schools, the Board provided teacher salaries and assistance with educational materials, but not the schools themselves. Where tent schools were established, attendance was irregular. Tents proved to be miserable places to conduct schools as they were hot in summer and cold in winter. They had earthen floors. Heating to keep out the cold was provided in dangerous fireplaces. An occasional consequence of teachers failing to extinguish fires properly was tents burning to the ground.

Miller’s disappearance and dismissal

Some five months after his appointment, the Board dispensed with Miller’s service at its meeting of 31 December 1852. Dissatisfaction with his efforts was cited as the reason, and in the process Miller was refused further salary installments.

During the five months of Miller’s employment the Board received only seven reports, one as a result of a meeting held at Bulla Bulla, northwest of Melbourne, the remaining six from the goldfields. In his report of 11 November 1852 (Forest Creek), Miller notified the Board that subscriptions to establish the tent school on the diggings had been coming in very slowly but advised that he had an amount of £83.2.6 in hand. He sought advice from the Commissioners about what to do with the funds. Miller suggested that he could pay for the erection of fireplaces, water closets and other ‘little things that can only be done on the spot’. The Board directed him to lodge all monies to the credit of the Board at the Bank of Australia. Kane included a personal letter with the Board’s advice to Miller but there was no response to the letter.

In his sixth report, 21 November 1852 from the Forest Creek diggings, Miller advised that he had an additional £10 on account of the planned schools. He made no reference to Kane’s advice concerning money already in Miller’s keeping. In effect Miller was now holding £93.2.6. The Board’s minutes record that Miller’s report of 21 November 1852 was the last correspondence received from him and that the amount of £93.2.6 had not been credited to the Board. Letters sent to Miller on 3 and 10 December were not acknowledged.

In the Government Gazettes of 11 May and 15 June 1853, unclaimed mail at the Melbourne Post Office for Miller was listed. Clearly Miller had made off between the time of his sixth report and the Board’s correspondence of 3 December 1852. That letter had requested Miller to ‘proceed to Melbourne and report to the Board without delay and to produce at the same time the diary of his proceedings’.

Bryce Ross, a vocal member of the community at Forest Creek and the goldfields’ correspondent for the Melbourne Morning Herald, complained about the delay in launching a school late in 1852, noting the Board’s ‘most extraordinary tardiness’. Ross would later learn that the Board’s inaction stemmed from an inability to believe that Miller had absconded with the funds. Consequently, Benjamin Kane took on the role of acting inspector. Kane was dispatched to Forest Creek to ascertain what had transpired during Miller’s time at the goldfield. He arrived at the diggings on 2 February 1853. His first report indicated that he had been unable to obtain any information regarding Miller, nor was he able to establish with certainty the amount of money held by Miller. It appeared to have been considerably more than one hundred pounds.

At a meeting on 18 February 1853 the Board decided to seek Miller’s whereabouts by placing advertisements in newspapers. At the 13 July 1853 meeting the Commissioners placed the matter of Miller’s misappropriation of public funds in the hands of the chief commissioner of police. Despite the best efforts of the Board to locate Miller, there was no trace of him. He had vanished.

In a private letter to Miller in November 1852, Kane had pressed the inspector to account for rumours that had reached the Board concerning Miller’s marriage, his association with a digging party, the matters in dispute with the Commissioners concerning his behaviour and other issues that Kane advised had ‘been calculated materially to lessen your influence among the people’. He also sought explanation for Miller’s non-attendance at a planned public meeting in Kyneton, causing the meeting to fail. Kane declared that he raised the issues with ‘friendly feeling’ towards the inspector because, ‘unless the issues were given satisfactory explanation, there will be a lack of that confidence between yourself and the Board—which is necessary for securing your own comfort and the due performance of your office’.

There was no response to Kane’s personal plea. Miller had chosen his path. No great effort was made to follow up on the search for the absconder. Given that National education in Victoria was in its infancy, and with animosity from religious interests towards National education, it is possible that knowledge of the affair was suppressed. Any scandal would have played into the hands of the Board’s detractors.

What happened to Inspector Miller?

A descendant provided some information on the fate of Miller. With a name change, William Knowles Milner and wife Mary Jane arrived in Hobart on 31 December 1852. Milner took over a Land, House and Inspection agency at 12 Elizabeth Street. Advertisements placed by Milner declared, ‘Money Advanced in sums varying from £100 to £5000 upon liberal terms’. Another asserted that ‘every accommodation given, in Loans or Money, for long or short periods, upon Real or Personal security’ could be made available. Milner was unsuccessful in this enterprise. In 1855 he joined his brother Maxwell to establish the Tasmanian Daily News. Although respected for its literary content and political commentary, the paper ended in debt after a circulation period of two to three years.

The brother, Maxwell Miller, gained an appointment with the Victorian National Board on 9 June 1854 as an inspector but four months later on 9 October 1854 was deemed to have been unreliable and lax in attending to his responsibilities and for speaking at public meetings in his district on subjects not directly connected to National education. The Board had not received any communication from him in thirteen of the twenty-two places he had claimed to have visited in 1854. In his application to join the Board Maxwell claimed that ‘I will venture to say that although there may be abler applicants, there is none who would discharge the duties of an inspector with more unflagging activity or more zealous industry’. He did not fulfill the promise.

In an attempt, perhaps, to make good the family name, Maxwell wrote in July 1855 that he wanted to pay back the ‘deficiency’ of his brother. The Board Secretary, Kane, responded that, although the outstanding amount was in excess of £100, Board records indicated that an amount of £93.2.6 was repayable. Whether this amount was repaid remains in doubt.

By January 1857 William Milner had taken up a teaching position at the Bellarine Church of England School in Victoria. It is uncertain why Milner (Miller) went back to Victoria or why, by 1860, he went to South Australia. He left positions in haste on each occasion. He died in 1861 while resident of the lunatic asylum at the Redruth Gaol in Burra, South Australia.

Miller and the history of Victorian public education

National Model and Training School, Melbourne, 1857. State Library of Victoria.

Miller’s contribution to education in the early years of the National Board was limited. The Board was inexperienced in administration and in its appointment of inspectors. Denominational or church schools had been well established in the colony and the new Board was regarded with skepticism by churches and other religious interests. Miller had to contend with much cynicism as he moved about the goldfields. He found that all too often promises of support amounted to little. Local ministers of religion would do their best to undermine any attempt to have their parishioners’ children poached by non-sectarian schools set up under the National system.

There was a limited pool of educated colonists who could take up the post of inspector. Miller was well qualified at law but had no teaching experience. Among other unsuccessful attempts to appoint inspectors there were successes also. Benjamin Kane, who had prior teaching experience at Launceston Grammar School, followed Miller and established himself as a competent, meticulous and industrious administrator. Kane held his position in colonial government education for nearly two decades being appointed secretary to the Common Schools Board in 1862. Where Miller failed, Kane succeeded in establishing National education, even on the goldfields.

The Board of Education established by the Common Schools Act (1862) had better success than its predecessor in the appointment of inspectors. The Board of Education was able to select experienced personnel from both the National and Denominational systems. The new Board of Education appointed Richard Hale Budd (Inspector General), Joseph Geary, Harry Sasse and John Sircom who were ex-Denominational Board inspectors, whilst Arthur Orlebar (Senior Inspector), Gilbert Wilson Brown, Henry Venables and Archibald Gilchrist were ex-National Board inspectors. With the disappointment that surfaced from Miller’s failure came the realisation that future appointees would require teaching qualifications and/or classroom teaching expertise.

Miller’s failure as inspector was in part the result of an inexperienced Board as well as the labour shortages associated with the gold rush. At the same time government systems of education, their establishment, their governance, and what qualifications might be required of their administrative personnel were uncertain in their early days. The era of the Boards would be followed later in the nineteenth century by ministries of education and public instruction. The duties and accountability of the inspectorate would be tightened. For the future also was the ‘payment by results‘ regime that allowed a fuller development of centralised and bureaucratic control of colonial government schools. Miller’s misadventures were a story associated with inventing a system that in the 1850s was far from ‘efficient’.

Glossary:

Common Christianity was an elusive idea that tempted nineteenth century non-church, government school founders in the Australian colonies. The idea was that common, ‘national’ schools could be founded for children from any Christian denomination on agreed, non-controversial elements of Christianity. Many of the Protestant denominations apart from the Church of England bishops and clergy were prepared to allow school curricula written on this basis. The Roman Catholic Church increased its opposition to the idea, rejecting it completely in the 1860s and 1870s.

Note:

Original materials consulted include Public Records Office of Victoria, VPRS 876, 877 and 880; and Redruth Gaol Letters Book.