Note: Photographs of Indigenous persons who may have passed away appear in this entry.

Formal schooling, as the invading British understood it, was alien to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Education among Indigenous peoples occurred quite satisfactorily without it. What needed to be learnt by young people was specific to their age and gender, and the local cultural ties, beliefs and practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Education occurred within families, broader kinship groups and clans. Across Australia there were some 250 language groups, each with their own cultural traditions based on origin legends, the ‘Dreaming’. Learning cultural traditions was a fundamental part of Indigenous education along with acquiring the skills required for food gathering and hunting, managing the land, trade, providing shelter and the multitude of activities required for communal life.

The British invasion began the long disruption that has not concluded in the twenty-first century: disruption to the social, cultural and economic bases of Indigenous lives, including education. Land occupied by the clans was systematically stolen and occupied by the British. With the addition of introduced diseases, Indigenous communities faced privation and collapse. At the same time, the resilience of individuals, families and communities should not be underestimated. Older commentary was prone to falsely announcing the end of Indigenous culture and community, most notoriously for Tasmania.

The schooling of young people in Britain had a long history, but the idea that all children should be sent to a school, regardless of gender, social class and ethno-racial origins, was very recent in the eighteenth century. In New South Wales in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the dominant attitude of the British governing caste towards the schooling of Indigenous children was similar to that concerning the children of convicts, convict children, and the labouring classes in general.

If schooling for the lower orders was to occur at all, it should be an agent of discipline, social control, Christianisation and preparing youth for useful occupations. The schooling of Indigenous children might also contribute by detaching them from their families, clans and cultures: ‘civilising’ them. Each of these aims, articulated from the earliest days of the British invasion was resisted by Indigenous peoples. The resistance was noted often. Samuel Marsden, an early colonial chaplain, was one of several in the governing caste who did so. Marsden established a seminary in Sydney (1815) to train Maori youth for leadership roles in New Zealand. He did not believe that similar work with Australian Indigenous youth held any prospect of cooperation or success.

From earliest colonial times schooling was considered a means of controlling those considered a danger to colonial projects, to social order, and the creation of a useful labouring class. At the same time, the apprenticeship of young people to colonists operating farms or town and village-based enterprises was usually considered more useful than putting young people in schools, but not always.

Pitjantjatjara children living as part of the Presbyterian mission (Ernabella) in South Australia. c 1946. National Library of Australia PIC/14192/400

Contexts for schooling Indigenous children and youth

Following invasion and ever expanding areas taken for white settlement, pastoral and mining enterprises, there were no treaties between colonial governments and Indigenous peoples. The terrible fiction of terra nullius, that Australian lands were neither occupied nor owned by Indigenous peoples, allowed often unrestrained pastoral and agricultural expansion into their lands. Considerable violence on the frontiers occurred as colonists attempted to displace and marginalise Indigenous communities.

Despite early judgements by the British governing caste that Aboriginal peoples were unpromising subjects for Christianisation and schooling, a belief grew that if young children could be removed from their families early enough then detachment from their communities and cultural traditions would allow the possibility of Christian conversion, and what went with it, the creation of loyal, obedient and honest servants and labourers.

Tentative attempts to school Aboriginal children began in the early nineteenth century. During the twentieth century Indigenous families and communities usually recognised the necessity of some European-style schooling, however, there was also a recognition that schools were sites of racial discrimination and deculturation. Going to school involved levels of compromise or negotiation. The models for how that schooling should occur changed over two centuries. Issues such as the aims of Indigenous education, the external or local control of schools, parental rights, appropriate curriculum, effective pedagogies, teacher preparation, languages of instruction and languages taught, and more, have constituted the changing politics, contexts and realities of the schooling of Indigenous children and youth.

At the same time, it should not be forgotten that through to the early twenty-first century elements of pre-invasion Indigenous education survive. An interview with Mrs Nganyintja Ilyatjari recorded in 1982 and reported elsewhere in this Dictionary [forthcoming], testifies to the strong survival of such education through the 1920s in the north-west of South Australia for example. The survival of a distinctive Indigenous education extended beyond the early part of the twentieth century and continues today. Oral history testimonies provide the evidence. The survival of Indigenous approaches to learning and education have been recognised in contemporary educational research, and has shaped consequent teacher education and practice. That non-Indigenous pedagogies do not always work satisfactorily with Indigenous children is perhaps a recent discovery for academic researchers, but known by Indigenous communities for a long time. A substantial literature on the requirements in terms of language, texts, teaching approaches and the recognition of the different ways Indigenous children learn from and relate to adults has rapidly developed from the late twentieth century.

The first schools

The first public schools in Australia, the orphan schools, were concerned to reform unruly and potentially unruly white children, ‘orphans’. The Native Institution, founded in 1815, first at Parramatta, then ‘Black Town’ in New South Wales, attempted to do much the same with Aboriginal children though there were no ‘orphans’ in Aboriginal societies. The Native Institution was not particularly successful, as few families were persuaded to enrol their children. Those who did were likely to have been attracted by the promise of food as much as education for their children as scarcity followed white settlement. Families visited their children. Deaths, runaways and the withdrawal of children by families were frequent. The school gave some comfort to those of the white population and European visitors who were sensitive to the dire effects of the destruction of Aboriginal society in the closely settled districts.

By 1820, of the thirty seven children enrolled in the Native Institution, ten had either died or returned to their communities. Elizabeth Shelley, the director after the death of her husband, wrote in 1838 that the project was a failure. The girls who married Aboriginal men returned to their communities or, in her words, ‘their old ways’, and boys who went to sea were not heard of again, by her at least. When she attempted to to talk religion with old girls they laughed, saying ‘they had forgotten all about it’. Earlier there had been a fleeting triumph at an Anniversary School Examination in Parramatta in 1819 where Aboriginal and European children demonstrated their proficiencies. The main prize was taken, to the disapproval of many British colonists, by an Aboriginal girl.

Christian missions to Indigenous peoples were active early. Lutherans opened a school in Adelaide soon after the colony was established in 1836. The early decision to produce texts in the Kaurna language, and teach in that language, were soon countermanded. Teaching in English, the ‘civilising mission’ and preparation for labour on farms displaced the earlier approach of bringing the Christian message to Aboriginal children in their own language. In 1838 German missionaries arrived to begin a mission and school for Aboriginal people in the Moreton Bay area of Queensland. This was a Protestant inter-denominational (Lutheran, Presbyterian and Pietist) effort with Moravian inspiration. In 1841, the school was operating for five hours a day. The curriculum included the alphabet, numbers, spelling and singing—including the learning of the Lord’s Prayer. The children were not submissive. They often refused school-work and indicated that they attended as a favour to the teacher who, in their opinion, did little work. One group of students went house to house reciting the Lord’s prayer, demanding payment for their performances.

One Wesleyan missionary near Goulburn despaired in 1842 that local Aboriginal people were not responding to the gospel, the cause being ‘so powerful their superstitions, and so frequent their quarrels’, and ‘their connection with the worst class of Europeans’. Resistance to European colonisation and schooling could take many forms, though accommodation necessarily occurred as well.

Well-meant philanthropy towards Indigenous people existed among members of the governing caste from early on. Attempts to take children into colonial households, treating them with kindness, and training them as servants and labourers with skills that could earn them a living, were usually short-lived. Philanthropy was increasingly destructive as the argument that children needed to be separated from their parents and communities developed strength. Boarding schools could be established for the purpose. The Poonindie school in South Australia, established in 1851 by the Anglican church, was one of many examples.

The founder of the Maloga mission and school on the River Murray in New South Wales in 1874 was shocked by the poverty and demoralisation of Aboriginal (Yorta Yorta) people in the area. The mission consequently established was run from the belief that Indigenous people were ‘childlike’, requiring strong supervision and for children’s schooling, a very basic curriculum. The school was criticised as quite inadequate by public education inspectors. The curriculum consisted largely of repeating and singing hymns and psalms. Acquired literacy levels were low. According to inspectors, boys were insufficiently prepared for low-level agricultural labour, as were girls for domestic service. The rules of Maloga were so authoritarian and culturally insensitive, and probably offensive, that the mission expelled numerous resident Indigenous families who were unable to reconcile themselves to the regime. The expulsions were followed by a withdrawal of many families, yet as was the case with many missions, a number of the young people educated in its school went on to lead in their communities.

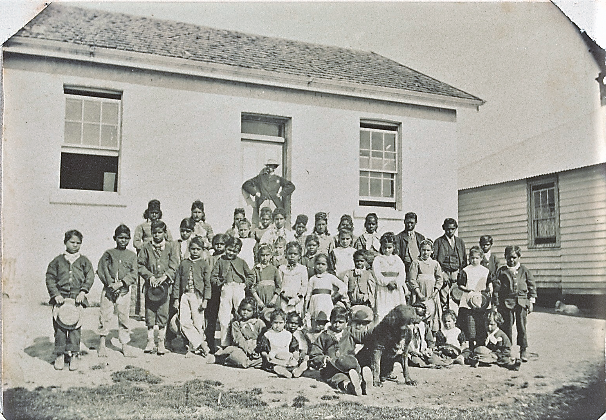

Students and teachers from Coranderrk, c 1878. State Library of Victoria, H41139/80

In Victoria, the relatively successful settlement of Coranderrk, established by the Kulin clan in 1863, was undermined in the 1870s by the efforts of the Aboriginal Protection Board to close it. As occurred in South Australia at Poonindie, neighbouring farmers wanted mission lands privatised for expanded farm holdings. The school within the Coranderrk Children’s Asylum and Dormitory outlasted the settlement, only closing in 1924, but it certainly shared the problems of similar institutions. Instruction there or at the Badger Creek State School rarely proceeded beyond the third standard. It was Board policy that upon turning fourteen, Aboriginal children had to be placed into ‘apprenticeships’. It was not a choice, and their education was specifically designed to prepare them for work. There were some exceptions, such as Joseph Wandin, who lived at Coranderrk and was a successful student at Badger Creek State School, becoming a student teacher there and going on to become a career teacher with the Education Department, qualifying in 1907 and working as a teacher until 1950. Nevertheless, most boys could only expect labouring jobs in agriculture, and girls, in domestic service.

An early policy of colonial governments was the establishment of protectors and protectorates for Aboriginal peoples. Later there were welfare boards. Protectors were paternalistic. Their resourcing was usually inadequate. Where Aboriginal reserves were established, they were ruled in an authoritarian manner, allowing few rights of movement, speech and association. This usually applied to mission settlements founded by churches as well. Where schools were begun, expectations were low, and teachers often unqualified and unsatisfactory. The probability of paid work beyond the menial or unskilled labouring at the completion of such schooling was minimal.

The formal education of children and youth was not the only reason for limited employment prospects. Racism among white colonists was prevalent, whether from ignorant, malignant or philanthropic origins, or greed. The low expectations by white employers of Indigenous peoples combined with the distressing social, economic and health circumstances of families and communities proceeding from the alienation of their lands and livelihoods meant that where schools were even available, their effectiveness was limited.

Post 1870s public and mission schools, and Indigenous families

Church missions ran many schools for Indigenous children through the nineteenth and well into the twentieth century, long after the time that churches were considered suitable providers of education for most non-Indigenous children. The stories arising from different schools at different times are mixed. Apparent successes came at a cost. Indigenous families were never passive recipients of schooling. Sometimes the missions and their schools offered protection from harsher realities, and that was valued, even if the surveillance, controls, loss of independence and attempts to displace and replace culture were not.

School children at the Hermannsberg mission, South Australia, c 1905. State Library of SA, B26752

The Hermannsburg Mission was established near the Finke River west of Alice Springs by Lutheran missionaries in 1877. A school was built in 1896. It included separate dormitories for boys and girls. Rations were distributed as an incentive for children to attend school. (Withholding rations also formed a punishment for a variety of causes, not only school resistance.) As had occurred much earlier for Lutheran efforts with the Kaurna in Adelaide, teachers and missionaries taught in the Arrente language and translated religious and other educational materials from English and German. In the 1930s the mission worked with some 100 children. The land on which the mission was built was returned from the Lutherans to the Arrente people in 1982. The school, renamed Ntaria, came under government control.

A student of the Hermannsburg school was the artist Albert (Elia) Namatjira (1902-1959). While attending the school he was separated from his parents, living in the boys’ dormitory. At thirteen years of age, his Indigenous education took precedence when he spent six months in the bush undergoing initiation. Despite his artistic success, and even the rare concession of Australian citizenship, there were attempts to patronise and control him for most of his life. Laws failing to recognise his obligation to share any largesse arising from the sale of his paintings with family almost landed him in gaol in 1957.

Saluting the flag of the colonisers (not all did in this photo). Point McLeay Mission, South Australia, 1912

Many Aboriginal families were forced to accept the paradoxical effects of conventional schooling. It could be destructive of family, community and culture, but it might also provide a possible basis for improved circumstances. The recognition by many families that schooling might be useful caused difficulties for the providers of public education who were often reluctant to invest in Aboriginal education and schooling. In theory public education should have been accessible to all, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. One way or another such access was conditional during the first century of public education (1870s-1970s), sometimes through formal regulation as in New South Wales and Western Australia, but as often through discriminatory regulations and practices of education departments, school administrators and teachers.

Segregated schooling, that is schools being provided exclusively for Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal children, had been common from earlier in the nineteenth century, but it rapidly developed from the 1870s.

For New South Wales, Jim Fletcher (1989) traced public school exclusions based on the ‘clean, clad and courteous’ policy. In that colony and then state, explicitly racist policies were implemented from the 1870s. The Education Department allowed school masters and mistresses and white parents to block the enrolment of Aboriginal children in public schools. Objections to the enrolment of Aboriginal children in public schools could occur for more or less explicit reasons as the following examples show. All had their foundation in racial discrimination.

- In 1883 at Yass, local Aboriginal children were expelled from the public school, the cleanliness, clothing and behaviour regulations were used to exclude them. The Catholic convent school offered to enrol them if it received government assistance. The 1880 Public Instruction Act had withdrawn all assistance to church-owned schools, and these Aboriginal children were no longer schooled as a result.

- When Aboriginal children were expelled in 1891 from Gulargambone Public School, the local grazier promised to build an alternative school. He did not, and the schooling of Gulargamborne Aboriginal children ceased for many years.

- At Karuah both Indigenous community and a local white teacher fought exclusions from the 1890s, but they happened anyway. Karuah Public School was not desegregated until the 1950s.

- In 1909, the children of the manager of Walhallow Aboriginal Station were mixed race and excluded from the public school. On appeal, the Education Department considered that their ‘light skin’ was perhaps light enough to allow re-enrolment. The Department took so long to determine the issue that the children were enrolled at another more accepting public school.

- At Wanaaring a demand for Aboriginal exclusion in 1915 was withdrawn when white parents discovered that the school, as a consequence, would close altogether for want of sufficient enrolments.

- At Huskisson in 1921, an Aboriginal man who had attended the local public school found his grandchildren excluded. White families planned to drive Aboriginal families away from the area for economic reasons, using school exclusion as a tactic. Indigenous and non-Indigenous families competed for fishing grounds from which they both made livings.

- At Batemans Bay, following exclusions in the 1920s, a campaign for the right to enrolment by the local Indigenous community, including a letter to King George V, succeeded, but the support of the school principal and local Education Department inspector had also been required.

Such stories are many across Australia, and they demonstrate the local variations and complexities of racially-based exclusions. In South Australia at Oodnadatta in the 1920s several white parents fought to exclude not only Aboriginal children from the public school, but also those from Afghan families. Specious arguments about the susceptibility of white children to disease from non-white children were used in this case and were commonly asserted elsewhere. Letters from Aboriginal families, pressing for their children to be given equal access to schools, can be found in the archives of the various state education departments. Although the public education systems often discriminated against Aboriginal families, many families continued to campaign and fight for school access for their children. There is the case of the Murray family discussed by Fletcher (1989) and several others where families and communities fought for better schooling for their children.

The newly founded state school on the Yarrabah Mission in North Queensland, 1893. Possible readings of this image and others like it are disturbing. State Library of New South Wales, SPF/1237

The newly founded state school on the Yarrabah Mission in North Queensland, 1893. Possible readings of this image and others like it are disturbing. State Library of New South Wales, SPF/1237

The provision of separate schools for Aboriginal children by governments and missions was both justification and strategy used to exclude Indigenous children from many public schools. A policy of ‘exclusion on demand’ operated across many jurisdictions but was formalised in New South Wales from 1899. White parents could demand exclusions, no grounds other than race being required, whether alternative segregated schools were available to Aboriginal children or not. As a result, Aboriginal children in many areas were denied schooling.

If children were able to attend school, it usually came at the price of having to devalue their own communities and cultures. The segregated schooling provided for Aboriginal children in Australia was consistently inferior to that provided for non-Indigenous. For Aboriginal children in public schools, expectations were low. Peter Board’s syllabus for Aboriginal primary education, introduced in 1916 in New South Wales, assumed the incapacity of Aboriginal students to meet the standard course of instruction. The assumption that post-school menial (paid or unpaid) labour for Aboriginal youth was the best that could be hoped for, remained common, but as important were the interests of landowners who sought access to a low-paid, uneducated workforce. It also served state and territory governments who occasionally acknowledged that it was harder to ‘control’ Aboriginal people who had been well educated.

In Queensland was the Barambah Native School. In 1917 an Education Department inspector reported on it. There is little doubt that much of his commentary applied across the segregated schools of Australia.

If the object … is to keep the children quiet, and out of mischief during the daytime and train them to be lazy … it is a success, but if the aim is to cultivate their intelligence, to give exercise to their self-activity, to train them to be industrious and self reliant with a fair knowledge of their class work when leaving, the school is a failure. (Quoted in Haebich, 2000, p. 394.)

There are other voices that could be heard here, such as those of the children and their parents, but the inspector was no doubt influenced by New Education ideas popular at the time. Control, passivity and discipline were no longer enough, ‘even’ for Indigenous children.

Torres Strait Islanders

School children, Murray Island, Torres Strait, Queensland, c 1895. Fryer Library, University of Queensland, UQFL 10/634

The Indigenous peoples of the Torres Strait islands had a different initial schooling history from those on mainland Australia. Although the islands between New Guinea and Cape York were claimed by Queensland in 1872, local communities were not dispossessed of their lands, and their economies and cultures were less damaged. The London Missionary Society took the lead in schooling with the usual aims of teaching literacy as a step towards Christian conversions. The Society’s first school was opened in 1873 on Murray Island. The Society had a long history of training Pacific islanders as missionaries and teachers, and they comprised the first and main teaching force in the Torres Strait. (They were often more rigorous in their religious training and proselytization than the white missionaries.) Schooling was generally considered useful by Islanders since it was not as directly associated with the destruction of economy, culture and society. On smaller islands than Murray, there was stronger resistance especially where conflict occurred over traditional child-rearing as well as educational practices.

This phase of schooling history did not last long. A new resident administrator appointed by the Queensland government from 1885 to 1905 was unimpressed with existing schools. White teachers replaced the mainly Samoan teachers. The Queensland government was suspicious that these teachers were seeking to control communities. The Queensland state school syllabus was introduced in the attempt to shape a tractable Indigenous labour force. There were many losses in the process. Mission teaching had supported vernacular (local language) literacy. The London Missionary Society founded the ambitious Papuan Gulf Native College on Murray Island. It lasted from 1879 to 1890, educating many Islander male youth. The College was intended as part of a stepping-stone strategy to Christianise Papua New Guinea.

From 1900 the Queensland Education Department took full control of schools in the Torres Strait islands and the problems of that department in educating Indigenous children and youth in the rest of Aboriginal Queensland were thenceforth shared with the islands. Most of the Education Department schools were classified as ‘provisional’. The consequence was minimally trained and unclassified teachers, poor buildings and limited educational resources in general.

Conclusion

The period from the 1780s to the 1920s, despite the foundation of the Australian Commonwealth in 1901, left the schooling of Aboriginal children and youth in the hands of church missions, colonial and then state governments. A newly racialised approach to social administration towards the end of the period increased the problems that Aboriginal families endured. This is discussed in the succeeding entry, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Schooling (2). Schools continued as unavailable or hostile to large numbers of Indigenous children and youth, despite the universal coverage and compulsory attendance aims of the post-1860s Education Acts in the different colonies and then states.

Notes:

(1) The historiography around Indigenous schooling in Australia is patchy. Some institutions, including missions and a number of schools, and some regions such as the Torres Strait Islands are better served, but cohesive national studies of Indigenous education are yet to be written. Sometimes the best studies are autobiographies and biographies, including recorded Indigenous oral histories. They often enable a close understanding of the material impacts of schools on Indigenous lives.

(2) The author thanks Beth Marsden, Geoffrey Stokes and Anthony Welch in the preparation of this entry. He welcomes corrections and suggestions for its improvement and development.