In an effort to cater for the rapidly increasing rural population in the eastern Australian colonies following the gold rushes in the 1850s, the introduction of the Robertson Land Act in New South Wales (NSW) in the 1860s and the spread of settlement, most government departments of public instruction instituted what became known as Half-time Schools (NSW) or Part-time Schools (Victoria) during the latter decades of the nineteenth century. These schools were very small primary schools in remote and sparsely populated rural districts of the Australian colonies and, after federation, the Australian states. They shared an itinerant teacher who was in charge of two schools, at each of which he taught for a few days per week, travelling between the schools during the week.

Half-time schools were first introduced in NSW in 1867 following the 1866 Education Act. Initially at least 20 children were required to be enrolled in two groups or sites of 10 children or more. Later, in 1898 the required attendance was reduced to 16 children, across the two schools.

Travelling schools took the form of a covered horse drawn wagon, or van, in the charge of an itinerant teacher who plied between remote farms and properties providing elementary schooling to very small groups of students, often the children of only a couple of families in very remote districts. In NSW, Queensland and Victoria initially, horse drawn vans were used by the teachers, until later, with the spread of the railway networks, railway carriages were utilized for specialized educational services, such as the Domestic Science travelling classroom in Queensland during the 1920s. In Western Australia the State Department of Education established a travelling school to meet the needs of children whose families were employed in the construction of the Trans-Australian Railway.[1]

Half-time school buildings were usually provided by small local communities which met the expenses of the erection of the buildings, usually constructed from local materials. They were often slab timber buildings with shingle or iron roofs. Wattle and daub construction was common.

New South Wales

Their size varied from small 3×4 metre shacks with earth floors to more substantial buildings as shown in the photographs of half-time schools in NSW in the publication Sydney and the Bush (1980).

An early itinerant teacher in the Victorian goldfields, late 1850s. From Blake, Pioneer Schools of Australia (1977). Education Department of Victoria.

Alan Barcan (1965) reports that in NSW the number of half-time schools taught by itinerant teachers spending a half day at each of two schools was six in 1867 and 101 in 1872. Barcan also provides statistics of the number of children in NSW enrolled in half-time schools as 267 in 1867 increasing to 1,707 in 1879. The itinerant teachers of half-time schools were appointed by the Department of Public Instruction and these schools were subject to regular inspection by a school inspector.

An Inspector’s report on a number of half-time schools in the Goulburn District of NSW was published in the Goulburn Herald and Chronicle on 17 July 17 1875. It accurately describes the conditions in these small rural schools. The first inspection report relates to the school at Upper Gundaroo, which shared an itinerant teacher with Sutton Half-time School, and the second example is Quialego Half-time School which shared an itinerant teacher with Springfield Half-time school.

Numbers enrolled: boys 11; girls 10, total 21. The school is worked in conjunction with Sutton half-time school. Some minor defects occur in the records. There are still no programmes of lessons, and others of the required wall documents are wanting. The enrolment includes nearly all the available children and the several features of discipline are tolerably satisfactory. Object lessons and drawing are omitted. The proficiency is moderate in each of the two classes.

Also:

Quialego Half-time School: Visited 21st October. Numbers enrolled: Boys 4; Girls 10; total, 14. A wooden floor and hat-pegs are badly wanted. All children in the locality are enrolled and they attend regularly and with fair punctuality. In point of order and general demeanour they have improved. The general discipline is now fairly satisfactory. Suitable instruction arrangements are in force. Results varying from tolerable in the first class to moderate in the second have been achieved.

Over the decades quite a number of half-time schools were upgraded to full-time provisional schools (see Glossary) as their enrolments increased and when there was some prospect for their continuation as fully staffed schools. For example, Sutton Public School started as a provisional school in 1871, was reduced to a half-time school with Upper Gunderoo half-time school from 1872 until 1877 when it was re-instated in 1880 as a provisional school, and in 1881 was then given the status of a public school. Then, as enrolments dropped, it reverted to a half-time school with Brooks Creek from 1897 to 1900, then half-time with Mulligans Flat School until 1903 when its enrolments increased and it was upgraded to public school status thereafter. (School histories such as these may be traced in the publication, Government Schools of New South Wales. See Reference list.)

Victoria

In the colony of Victoria half-time schools (part-time schools) were introduced around the same time as in NSW in 1869. Quoting from the Government Gazette (Board of Education, Eighth Report 1869):

In thinly populated districts the Board of Education may grant aid by a salary to a teacher, who shall give instruction in one or two schools as the requirements of the locality may necessitate. No aid will be granted towards building or furniture.

In the case of half-time schools the teacher will be expected to divide his time between the schools under his charge with the view of effecting the greatest amount of good. It is recommended that he devote two and a half hours each day to the teaching of each school; but should any other arrangement be found more suitable, such may be adopted, the sanction of the Board having previously been obtained.

Where there is one school the average must not be less than fifteen [pupils], and where there are two the average at each must not be less than ten.

Travelling Schools

The first travelling schools appear to have been introduced in the first decade of the twentieth century. In some cases, where space in a family home was limited, the teacher held classes in the van, or on the ground surrounding the van, or in a room set aside for the class in the farmhouses serviced by the itinerant teacher.[2]

New South Wales

There were only three travelling schools in NSW, the first beginning in 1908. One was based in the Ivanhoe district, one in the Inverell-Collarenabri district, and one in the Narrabri Inspectorate.

A description of the van or wagon used by the early travelling schools is contained in a brief report in the Inverell Times, 6 March 1914:

An interesting little ceremony took place in Inverell on Thursday morning when Mr. School Inspector Noble commissioned a travelling school van, the second in the

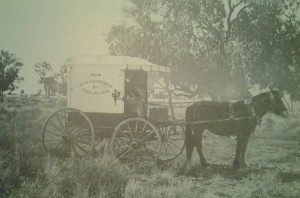

- Early travelling school in NSW, 1908. For the Narrabri district. Illus. 262. Sydney and the Bush (1980). NSW Department of Education

State. The van is fitted with lockers for provisions and books and sleeping accommodation for one teacher. The harness and van were manufactured locally. The first trip outback will occupy about six weeks. Mr. Bisley is the teacher in charge of the van. The Mayor and representatives of the Parents and Citizens’ Association were present at the commissioning.

It appears that the travelling teacher was expected to be entirely self-sufficient, not only in the transport of his teaching equipment, books, maps and slates etc., but also in respect of his personal accommodation needs. A lengthy article appearing in the Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, on 13 January 1909 provides further details of the nature of the NSW Travelling School program.

Such a scheme as this has been inaugurated in the Narrabri inspectorate, in a distance situated about 30 miles north-west from Burren Junction, among the settlers between Mercadool, Bulyeroi, and Merrywinebone. A couple of hours in the train from Burren Junction bring us to Eton Siding, a little railway platform. The settlers to be benefited are situated around this locality. All the participants are small landholders. The first teaching station, of which there are four, is situated about six miles from the siding; the second is about seven miles further on, while a distance of 10 miles separates the second and third, the fourth being some 13 miles from Eton siding on the opposite side. Altogether seven families are to be served by the system, comprising some thirty children. It is estimated that the cost of education will not exceed seven pounds ten shillings per annum per child. Each of the centres will be visited by the travelling school once every four weeks, the teacher remaining in each place for one week.

The article goes on to explain that the teacher chosen for this travelling school was trained as a pupil-teacher, “He is a holder of a St. John’s Ambulance Certificate and of Departmental Certificates in drawing and brushwork; is a good amateur photographer, is skilled in the use of the Magic Lantern and in the manufacture of slides for it.” He was also experienced in the management of horses. In addition to harness and fittings for the van it was stated that, for the teacher’s comfort, bedding, lamps, and camp requisites were provided. The wagonette was a covered vehicle, 7 feet long and 3 feet 6 inches wide with a cover 5 feet high. It was expected to last 15 years, and a sum of 24 pounds was allocated for annual maintenance and the depreciation of equipment. The vehicle was waterproofed.

The Report of the NSW Minister for Education in 1914 praised the NSW travelling schools. In referring to the Inverell Travelling School he reported that it had completed five circuits of the outback, had travelled 1,278 miles and that 47 children had received instruction. The teachers of travelling schools carried with them a variety of lesson and reading books appropriate to the ages of the children in each district. Selected books were left with each family whose adult members were requested to help their children learn their lessons using the books as an aid in preparation for the teacher’s next visit.

Queensland

Taking home science to rural Queensland. From the 1920s to 1967 there were railway carriages equipped to teach. State Library of Queensland.

In Queensland, in addition to the type of travelling school initially used in NSW, in 1923 the Queensland Department of Education introduced a special Domestic Science Travelling School railway carriage, connected to the state railway network, designed to visit outback districts. (See Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, 17 October 1923). This carriage was adapted for the teaching of Domestic Science to girls in the more remote and sparsely settled districts where the existing small schools were not equipped or staffed for teaching Domestic Science subjects. The carriages were 43 feet long and contained “a fully equipped kitchen, a sink and water supply and draining board” and also a large double wood burning oven, a crockery cupboard with special fittings to avoid breakages, ice chest, food safe and shelves and cupboards for aluminium saucepans and other kitchen utensils. There were work tables that students and a female domestic science teacher were to use. A Singer sewing machine was provided for dressmaking classes.

Each carriage had a separate compartment for the accommodation and use of the teacher, and also a fitting room for the dressmaking classes. The carriage would remain in a siding of a remote district for up to six or seven weeks. Instruction booklets, prepared by the Department, were printed for use in cookery, laundry, health and hygiene lessons. Initially the first carriage was intended to visit the Goondiwindi district. Other carriages were to service the Townsville district and Cloncurry district later in 1924.

Rural and remote area schooling

Just as the half-time and part-time schools of the colonies and states of Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland contributed significantly to the education of remotely located school children during the latter decades of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the travelling schools and itinerant teachers of the early decades of the twentieth century also made a major contribution to rural education.

Once the Australian colonies and states committed themselves to compulsory schooling, usually from the 1870s, there was a great problem in how education would be delivered in sparsely settled rural and remote communities. Governments, their education and public instruction departments, were required to be inventive. Correspondence schooling was one answer, but travelling and part/half time schools also played an important role for many decades.

Glossary:

Provisional schools in New South Wales lasted from 1867 to 1957. They were elementary schools that did not reach the number of enrolments for the establishment of a full public school. The minimum and maximum number of enrolments varied over time. They were usually staffed by untrained teachers or teachers on the lowest grades. Parents usually provided the building or met its cost.

Notes:

(1) One of the best authorities in this field of educational history is Ashley Freeman. His two theses are listed in the references below.

(2) Examples of the few surviving travelling school wagons may be seen in the New England Education Museum in Armidale NSW and also at the Pioneer Museum in Swan Hill, Victoria.