The Educational Workers League (EWL) was formed in Sydney in June and July 1931 by a group of teachers in the context of the Great Depression and frustration with the New South Wales Teachers Federation. Its existence spanned five years of crippling economic crisis, political upheaval and social distress. Although membership remained small, the League, its formation, its members, its activities and policies were significant in the immediate and long-term history of the Teachers Federation; in movements for change and reform in teachers’ employment and working conditions; and in the reform of the education provided for the children of the state.

Formation

The New South Wales Teachers Federation had existed since 1918 as a registered trade union. From 1927 to mid-1929 the Federation argued a salary claim before the Crown Employees (Teachers) Conciliation Committee. Many teachers were unhappy with the result of the long-drawn out proceedings and wanted to lodge an appeal. The Federation Executive, however, declined to do this. The members of the Assistants Association, one of several associations that existed within the Federation, were particularly angry, feeling that headmasters and the current leadership had betrayed the interests of the large body of classroom teachers. Then, just after teacher’s salaries had risen slightly, they were cut when the state government passed the Public Service (Salaries Reduction) Act (1930, No. 21). Fears of the dismissal of married women teachers, already discriminated against, were rife (realised by the passing of the New South Wales Married Women (Lecturers and Teachers) Dismissal Act (1932, No. 28)). From this anger, frustration, and fear some teachers considered what a new organisation might be able to achieve.

Depression conditions led to a situation where radical groups on both sides of politics gathered support and grew in influence. The Communist Party of Australia (CPA) grew in numbers and influence, as did radical socialist organisations. The teachers who met together in June and July 1931 to form the EWL were, generally speaking, radical socialists or disaffected Labor supporters. Some were members of the CPA and some would later join this organisation. The two prominent Assistant Association members who most wanted to form a new organisation, Alfred Paddison and Sam Lewis, appear to have had quite different visions for the new body. Paddison, President of the Assistants Association, was so frustrated with the Federation Executive and Council, that he wanted to form an alternative, “breakaway” union. This soon brought him and the Assistants into serious conflict with Federation Council. Lewis, Vice President of the Assistants, was quick to deny, in the following months, that the EWL was a “breakaway.” He repeated this so often, that it is obvious that the threat persisted within the Federation and the wider community.

After several preliminary meetings, about 30 teachers met on 25 July 1931 to elect officers and adopt a Constitution. Paddison was elected President and Lewis Secretary. Foundation members, or those joining very soon after, included Harry Norington, L.C (Lewis) Rodd, Clarice McNamara, Annie Isaacs, and Hettie Ross. These teachers were active within the Teachers Federation; most had been born at the turn of the century and were now around 30 years old. They held visions and ideas for a reformed society and reformed education. Their ideals were incorporated in the Constitution. Paddison, although elected as President of the new EWL, was antagonistic to the Constitution, the authorship attributed to Lewis, and soon resigned from his position as President, subsequently filled by Harry Norington.

First Constitution July 1931

When it was published the Constitution caused consternation, even hysteria, as expressed in opinion columns and editorials of newspapers throughout the state. Such exposure brought the EWL wide, if controversial publicity.

The most contentious sections of the Constitution proved to be its opening “Preamble” along with certain of its “Immediate Demands”. The Preamble began: “The efficiency and completeness of a system of education are fundamentally dependent on economic conditions”. Teachers needed to be involved in “the organised struggle of the workers” with the overall objective of the EWL being the abolition of capitalism and the establishment of a “Workers’ Socialist Commonwealth”.

Many readers, including teachers, would get no further than this preamble before condemning the EWL. They would miss reading further considered demands for reform in conditions of teachers’ employment and working environments, and in children’s wellbeing and education that many teachers would have supported. The EWL wanted an overhaul of accreditation and promotion of teachers, with annual increments replacing the cumbersome grade and class system; an increase in salaries; equal pay for women; no discrimination against married women; and a clerk appointed to each large school. For children, the EWL wanted to ensure adequate food and clothing; a raised leaving age of 16 years; free education throughout primary, secondary and tertiary levels with allowances to those over 14 years; reduced class sizes; adequate playgrounds; up-to-date sanitation; and the provision of aids and materials for learning.

Opposition focused on section D of the demands which called for the abolition of the celebration of Empire Day in schools and “narrow nationalism” more generally in the curriculum. Scripture and religious instruction should also be withdrawn.

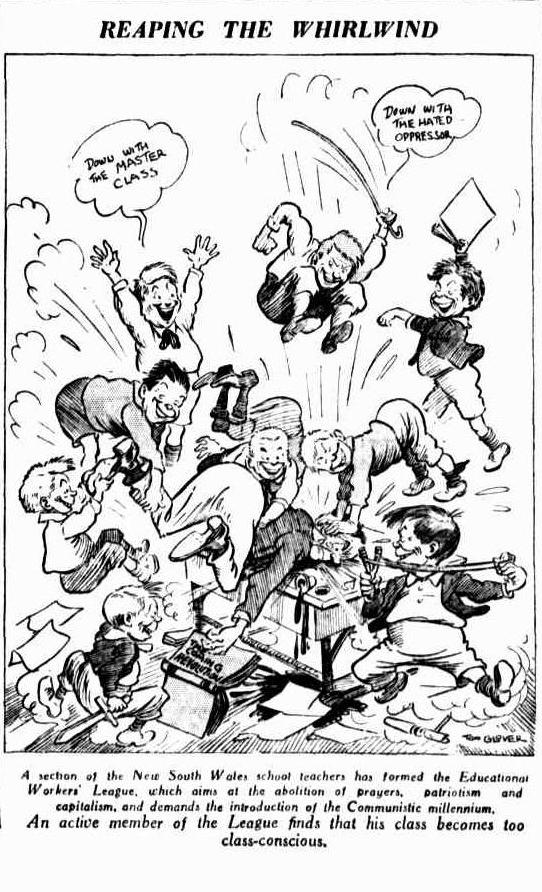

Newspaper columns and letters carried emotive headlines: “Teachers ‘Red’ Objective: Against Scripture and Empire Day”; “Teachers want no prayers or patriotism”; and “Communism at work” were examples. The recently formed Sane Democracy League, led by Millicent Preston Stanley, was particularly virulent in its criticism, writing letters, calling meetings and leading a deputation to the Minister for Education. The Sun’s cartoonist had fun punning with “class” warfare. Much more considered criticism came from Peter Board, retired from his position of Under-Secretary of the Department of Education, but still held in high regard.

Lewis always stressed that the EWL was not affiliated to any political party. Its main purpose was to organise vigorous resistance to attacks on teachers’ wages and employment conditions in the face of totally ineffective action on the part of the Teachers Federation.

Second Constitution 1932

This purpose was reiterated in a substantial revision of the EWL’s Constitution adopted in December 1932. The contentious preamble was replaced by a Foreword that referred to attacks made on conditions of educational workers since 1929 and the futile actions of the Federation. New, active methods were needed. Educational workers had to unite to fight for their material welfare, organise and co-operate with other workers. The EWL endeavoured to lead workers in this defence. A section on “Immediate Demands” repeated much of the first Constitution. Celebrations and teachings that assisted the development of “narrow nationalism” were still proscribed, but Empire Day was not specifically mentioned, nor were scripture lessons.

Unlike the first Constitution, this one developed the idea of the EWL as a body that would be composed of local school groups, district committees, state sections, and a national executive. Although some local school committees were presumably formed, the development of the EWL into a national organisation never eventuated.

Educational Workers League 1931-1932

In August and September 1931, the EWL circulated written protests against the Public Service Salaries Act No. 2 (1931, No. 29), passed in August. Members spoke out within the Teachers Federation and at the Federation’s Annual Conference in December. Members also represented the EWL at other working-class conferences and participated in the May Day procession. Three lectures were organised in 1931, one given by Professor John Anderson from the University of Sydney who spoke on “Education and Politics” and succeeded in attracting more criticism from the press over the teaching of communism in schools. In early 1932, the EWL protested against the refusal of the Department of Education to employ 500 ex-students who had just completed Teachers College. Later in the year, protest was directed at the passing of the New South Wales Married Women (Lecturers and Teachers) Dismissal Act (1932, No. 28). The EWL disputed the idea that getting rid of married women would make the employment of ex-students (albeit on a half-time basis) a beneficial outcome. The attempt to pit various groups against one-another had to be resisted. In August 1932, the EWL brought out the first issue of a small journal: The Educational Worker, which would continue in existence until 1936 and probably reached a much wider audience than the body’s membership.

Defence of Beatrice Taylor

Early in 1932, the EWL raised money to pay for a teacher to join an excursion to Russia arranged by the Friends of the Soviet Union, an organisation formed in 1930 with the aim of informing the public about the achievements of Soviet Russia and combating negative opinions. Its first organised tour to Russia left Sydney in March 1932, with arrangements for delegates to observe reformed economic and cultural institutions. Many teachers, including the founders of the EWL, had taken great interest in how communism was working out in Soviet Russia during the 1920s, and were keen to send an Australian teacher to observe educational reform. The Teachers Federation declined to send a delegate, but members of the EWL were determined to raise funds to sponsor teacher Beatrice Taylor who was active in the Federation, but neither a member of the EWL, nor of the Communist Party.

When she returned to Sydney in September 1932, many groups were interested in Taylor’s lectures where she spoke about education and other aspects of life in Russia. The EWL devoted its journal to her articles. Then, in December, Taylor was suspended by the Department of Education for her alleged political activities and ordered to appear before the Public Service Board on a date set for January. The EWL supported a successful campaign for her reinstatement, with Sam Lewis as secretary of the Beatrice Taylor Defence Committee. Strong support was given by many unions, including the Teachers Federation, and mass meetings were attended by those who recognised this as an attack on the civil rights of public servants and the principle of freedom of speech. L.C. Rodd organised a boycott at Taylor’s school, Paddington Public, for Tuesday 31 January 1933, the first day of the school year. Parents were requested to keep their children home, and it appears that about half of the children were absent. Crowds gathered at the school with placards, and scuffles with police gained the attention of the press and public. The hearing before the Public Service Board, also on 31 January, was brief. Barrister Clive Evatt was successful in his defence and the Board reinstated Taylor.

Taylor’s victory was, and in recent histories of the Teachers Federation continues to be, widely celebrated as establishing teachers’ rights to involve themselves in political debate.

It was a defining moment for the EWL whose credibility was established within trade unions and other working-class organisations. Press coverage was extensive, not only in New South Wales, but in all the Australian states. The combination of many organisations, the large mass meetings and the community supported action at Paddington School sent a message to teachers and other public servants that resistance of this type could be effective.

Educational Workers League 1933-1936

While the EWL never again hit the headlines as it had during the Beatrice Taylor affair, its consistent and active support for salaries restoration and its ongoing resistance to the conservative leadership of the Federation were influential and eventually effective.

In 1933 the EWL co-operated in the holding of a conference “To demand Provision for School Children and Growing Youth” which called for government provision of food and clothing for children suffering because their parents were unemployed. Its monthly journal continued, collecting together a variety of articles, most of which were unsigned to prevent personal retaliation. They dealt with topics such as the likelihood of another war and support for peace initiatives and the effects of the depression on education in other countries. Sam Lewis consistently signed his contributions and listed his address for subscriptions. L.C. Rodd, an early outspoken advocate for revisionist history, contributed a series of articles under the title “The Lies we Teach”.

Through 1933 and 1934, the EWL remained outspokenly critical of the Federation’s leadership, particularly its president, Charles Currey, the “policy of passivity: super-respectable, polite negotiations between a few officials and the Government” (Educational Worker, December 1933, p. 1) and the failure to co-operate with other Public Service organisations. The EWL continued to protest salaries reduction and to support unemployed ex-students and married women.

By 1934, however, there were some hopeful developments within the Federation. It appointed a Salaries Reduction Committee and at its December Conference in 1933 it adopted a new platform with five planks. All had earlier been included as “demands” in the EWL’s Constitution:

- 1. Increase of basic rate of salaries of teachers to £312 per annum, and displacement of “grade” and “class” system by a system of annual increments.

- 2. Increase of payments to all teacher- trainees to £104 per annum.

- 3. Equal pay and employment rights for both sexes, with no discrimination against married women.

- 4. Full-time employment of all ex-trainees of the Teachers’ College at full ex-students’ rates.

- 5. Reduction of size of classes to not more than thirty pupils.

- (As printed in Educational Worker, December 1934, p. 3)

A report of the annual meeting of the EWL in December 1934 was optimistic. Its prestige and membership had grown and the Federation and general body of teachers were increasingly favourable towards the League’s proposals for the restoration of salaries. EWL members had worked within the Federation, with unemployed ex-students, in the schools and districts, amongst married women teachers, in co-operation with other public servants and in the movement against war and fascism.

At its December 1934 Conference, the Federation, urged by EWL members, made further decisions that the EWL applauded. The President, Arthur McGuiness, was prepared for active protest, and Federation joined other public servants to organise a mass meeting on 14 March 1935 which saw successful outcomes that began to redress salaries. Additionally, a Constitutional Committee was set up to consider substantial changes to the structure of Federation that would be based on school and district committees. This was how the EWL had envisioned its own structure. Sam Lewis and Harry Norington were both on the Constitutional Committee.

Through 1935 and into 1936, the EWL began a concerted push for all teachers to join the Federation. In early 1936, Lewis praised the Federation’s new executive which was more representative of the assistant teachers who made up the vast majority of the teaching workforce. The proposed constitutional change for school branches and district confederations with direct representation on Council were adopted and further combined action for salaries restoration was planned.

The League disbands

On 9 May 1936 the League disbanded. In a formal letter to the Federation Executive and the editor of Education, Lewis explained: “It is felt that the continued existence of the League at the present moment when it supports much of the Federation policy and methods, can lead only to misunderstanding” (Education, June 1936, p. 248).

Mass action continued through 1936-1937 until salary restoration was achieved in 1937. Lewis often credited the EWL with bringing about the change of tactics within Federation and their successful outcome. Meanwhile, the teachers who comprised the League became increasingly influential within the Federation.

Significance of the Educational Workers League

In a history of the Teachers Federation written in 1969, Matt Kennett, former member of the EWL and General Secretary of the Federation in the 1960s, believed that the depression years of the 1930s witnessed profound and lasting change to the Federation with the emergence of new knowledge, a new outlook, more vigorous methods, and a greater appreciation of unionism in a highly competitive society (p. 71). The significance of the EWL within this shift was decisive.

Sam Lewis was elected Deputy President of the Federation in 1943 and President from 1945 to 1952. From 1958 to 1964 he was again Deputy President and President 1964 to 1967. In the 1940s and 50s, Lewis had to defend himself from recurring attacks by those opposed to his communist affiliation. Evidently the EWL was often brought into the debate and Lewis would reiterate that the EWL had not been not a communist front, just as it had never been an attempt at a “breakaway” union.

Nevertheless, the EWL and its influence on the Teachers Federation conformed to a general trend observed by labour historians in which communists moved into positions of influence within trade unions in the second half of the 1930s and developed campaigns for salary restoration and better conditions.

Apart from tactics, the EWL members carried enthusiasm for their policies into the Federation. Their advocacy for reform to existing teacher inspection and promotion procedures, equal pay for women, married women’s rights, clerical assistance for schools, a raising of the school leaving age, reduced class sizes, and other reforms for schools and schooling were absorbed into Federation policy and advocacy. Gradually, sometimes very slowly, many were achieved.