Victoria established compulsory schooling for all children in 1872, but there were long-standing problems of access for children in some rural and remote areas of the state. One possible solution that enabled governments to meet their educational obligations was to introduce correspondence schooling. This was effective for families isolated from other families with children. It might also mean that one teacher schools in tiny communities could be closed, or not established at all. In the early part of the twentieth century the goal of efficiency in the delivery of education was important for governments.

Correspondence tuition for Victorian school children had relatively simple beginnings and initially there was no ‘grand plan’ for what the school would eventually become. While it did not take long for correspondence lessons to be available to primary and secondary students in remote areas throughout the state, correspondence education in fact began with young teachers employed in remote areas of Victoria. It was suggested as a means of upgrading the qualifications of those teaching in classrooms too far away to attend classes at the Melbourne Teachers’ College.

The extension of this service to Victorian school children in 1914 was a breakthrough for primary and later secondary education, not only within this State but in other Australian states, and by the 1930s there were requests from educational institutions overseas for information and teaching materials. Victoria was the first in Australia to provide such a service and New South Wales correspondence schooling soon followed in 1916, after a mother’s request there, as well as Tasmania and Western Australia (1918), South Australia (1920) and Queensland (1922).

The role of Victoria’s Correspondence School (CSV) in nation building was identified in a 1936 study by A.T. Brown who pointed out that giving their children educational opportunity was ‘in some way repaying the pioneers who were prepared to move away from the city and undertake the development of the state’s natural resources’ (Brown, 1936, p.10). Services such as schools and medical aid considered essential in suburban areas were absent in the remote bush, and families relied upon their own initiative and available resources to survive.

A mother’s letter that began it all

In 1914, Neill, Evan and Allan Prewett lived with their parents in a logging settlement in the Otway Ranges, eight miles from the nearest school, when their mother, Mrs Mabel Prewett, wrote to the Director of Education, Frank Tate, requesting help to educate her sons. This letter found its way to James McRae, then Vice-Principal of Melbourne Teachers’ College.

Under McRae’s direction, six volunteer trainees designed primary lessons to post to Neill and Evan. Each fortnight, hand-written lessons were posted to pupils who, supervised by their parents, completed these ‘sets’ before posting them back to their teachers. Corrected work was returned, accompanied by helpful comments in a personal letter from their teacher.

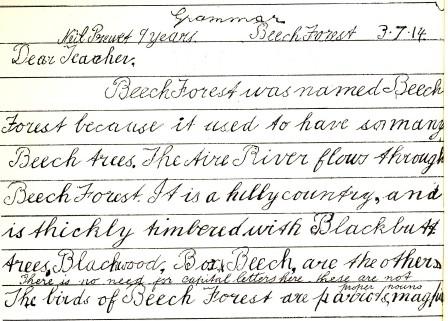

The lessons included studies of pupils’ local environment. In 1915, Neill Prewett described Beech Forest and the birds: ‘parrots, magpies, thrushes, robins, jackass, hawks, eagles, owls and others whose names I do not know’; and the farm animals: ‘two pigs, one big one and one little one, two dogs, one grey mare …’ He wrote of his favourite sunflowers, the fern-roots that must be removed and the rabbits that destroyed garden plants while the fence kept other animals out. In the sky above, ‘the cirrus and nimbus [clouds] are high up, and stratus and cumulus are low down.’ Neill also wrote of the historical characters and concepts introduced to him in lessons, including William Tell, Florence Nightingale, Joan of Arc and the history of Magna Carta.

Extract from workbook exercise sent by Neill Prewett to his correspondence teacher in July 1914. In possession of Virtual School Victoria. Used with permission.

His teacher wrote to Evan that ‘It was a pleasure to correct the work … The work was splendid but I was especially pleased with the neat arrangement of it … Tell me next time which sums you find difficult and I will give you more practice in those’.

While the older boys had attended a mainstream primary school for a short period prior to the family’s move to Beech Forest, younger brother Allan was to complete his entire primary school education by correspondence.

Mrs Prewett’s letter was soon followed by those from other parents seeking similar assistance so that, by 1916, the numbers requiring correspondence lessons exceeded the volunteer student teachers’ available time to cater for them. New facilities and teachers were required to cope with the demand and in that year, a Correspondence Branch was established within Faraday Street Primary School in Carlton that would later move, with increasing numbers of staff, to larger, though still temporary, spaces in City Road, South Melbourne and Bell Street, Fitzroy.

Secondary correspondence tuition for the Intermediate Certificate commenced in 1922, offering the subjects of English, History, Geography, Drawing, Geometry, Arithmetic, Algebra, French, Latin and Commercial Principles. In 1925, James McRae, by then Chief Inspector of Schools, reported favourably on the large numbers of correspondence students who passed these examinations and in 1928 correspondence tuition was extended to students preparing for the Leaving Certificate who could choose from English, History, Mathematics 1, 2 & 3, Economics, French, Agricultural Science and Drawing.

A growing respect for the educational opportunities offered by the Victorian Correspondence School eventually drew enquiries from interstate and overseas educators. In 1930 Miss M. Whitford, in charge of the Primary section, was invited to institute a similar system in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Requests for information and examples of lessons were to follow from the USSR, Scotland, Vietnam, USA, Canada, Belgian Congo, Patagonia and other countries.

The Correspondence School Victoria (CSV) finds a home of its own

Formally named the Correspondence School of Victoria (CSV) in 1932, both primary and secondary correspondence sections settled permanently at the vacant State School 2511 Napier Street, Fitzroy. In his appraisal of correspondence tuition in Victoria, Brown claimed:

from this time we can really begin to speak of tuition by correspondence as one definite school with its own aims, its own staff, buildings, students and Principal. It will also be from this time that the school as a whole will be able to progress, and to build around itself a host of traditions and glories perhaps greater and in many ways more romantic than any other school can hope to do. (Brown, 1936, p.9)

![Napier Street State School, Fitzroy SS2511, home of CSV 1932-1969. In possession of Virtual School Victoria. Used with permission.]](https://dehanz.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Napier-St-School-212x300.jpg)

Napier Street State School, Fitzroy SS2511, home of CSV 1932-1969. In possession of Virtual School Victoria. Used with permission.

The new Principal, Mr Morris Hambrook, like many of his teachers, had served in the first world war. A number of staff members who had returned with disabilities continued teaching effectively at the School, an opportunity that would otherwise have been denied them.

By 1935, the means of giving their pupils a sense of community were addressed by introducing a school magazine, a school badge and motto. The badge, designed as an open book with a lighted torch between its pages and the words ‘Opportunity and Perseverance’, reflected the educational opportunity the school offered to those who persevered against the odds. ‘The Mailman’, produced at the end of each school year, included poetry, stories, nature study articles, jokes, letters, photographs and art work by CSV primary and secondary pupils. Each pupil, ‘from the snows of Omeo to the heat of India’ (Brown, 1936 p.13) received the magazine that celebrated their diverse daily lives and experiences and reinforced a sense of belonging to a unique school community ‘across the distance’.

Michael James, India, doing his ‘school’, The Mailman, 1935. In possession of Virtual School Victoria. Used with permission.

In 1937, Melbourne newspaper The Argus described ‘Victoria’s largest school’ of 2,300 pupils who ‘learn their lessons in lighthouses and circus tents, in lonely farmhouses and in mission stations, in Victoria and abroad’. Yet, ‘the teachers know each pupil more intimately than if he were one of a large class in a city school … Tons of paper and gallons of ink flow out from Napier Street in personal letters and into Napier Street again in replies from children.’

In 1964, when the Correspondence School celebrated 50 years of providing tuition for primary students, the Napier Street school was described in an article, ‘Fifty Years Via the Mail-Bag’, published in The Educational Magazine:

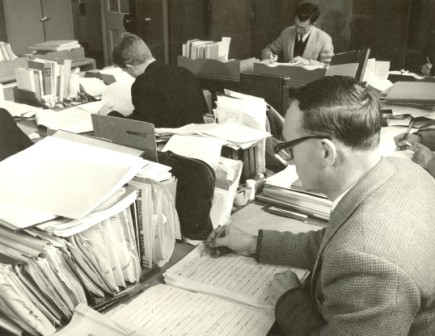

Fronting a quiet street in Fitzroy … stands a brick school of two storeys built in 1882. Here is housed the Education Department’s Correspondence School, the only one of its kind in Victoria. It is a remarkable school, for now through its impressive nine-foot double doors, newly painted blue, no pupils pass: those who work there are teachers only, more than 90 of them, primary and secondary, permanent and temporary, part-time and full-time. Almost cloister-like conditions reign in contrast to the hurly-burly of the ordinary school. Here, secondary teachers [in other schools] may be interested to know, every day is correction day… The origins of school lessons via the mail-bag is probably not so well known as it deserves to be (Victoria has achieved world distinction in this field of education) nor are the special services rendered by the Correspondence School today…

Correspondence teachers at work, Napier Street Fitzroy, 1960s.

In possession of Virtual School Victoria. Used with permission.

The pioneering work of Miss Mona Tobias and the Handicapped Section

In 1936, Brown identified qualities essential for effective correspondence school teachers including ‘a sympathetic nature, and a thorough understanding of educational methods … a desire to undertake this type of work, a thoroughness in all correction, and a ready response to all calls for aid’ (Brown, 1936, p.21). Such qualities were evident in the response to epidemics that crippled many children during the late 1930s and throughout the following two decades.

In the 1930s the Physically Handicapped Section of the CSV was established during the poliomyelitis epidemics. In her role as Honorary Medical Officer, Physiotherapy Department, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Jean Macnamara wrote in April 1954 of her experience working with teachers at the CSV who exemplified

qualities of selflessness, an ability to steady and inspire the parents where help is fundamental to the correspondence plan, even for the brilliant child; an appreciation of the need for, and ability and initiative to devise means to awaken in the children receiving correspondence lessons, the desire to learn.

Notable was the ground-breaking work of Miss E.M. (Mona) Tobias who, initially at her own expense and in her own time, visited homes and contributed to the team’s objective of maximum physical improvement, often with equipment she designed and provided for each individual child.

![Identified only as 'Carolyn, 1950s' the young CS student, with her mother, uses learning materials prepared by Mona Tobias. PROV: Photographs, Negatives and Slides [Education History Unit], VPRS 14514/P0001 Unit 11.](https://dehanz.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Carolyn-1950s-300x238.jpg)

Identified only as ‘Carolyn, 1950s’ the young CS student, with her mother, uses learning materials prepared by Mona Tobias. PROV: Photographs, Negatives and Slides [Education History Unit], VPRS 14514/P0001 Unit 11.

In a letter of commendation written in March 1954, Dr Henry Sinn, Consulting Paediatrician at the Royal Children’s Hospital, wrote that over the many years he had known Miss Mona Tobias, he had

learned to respect and admire her many outstanding characteristics as an educationalist and as a humanist. I know of no-one more painstaking, more patient, more thorough in the education of children … Her great charity and kindness are legendary in the medical circles in which I move. Her work with the handicapped child is without parallel. I personally regard her as the most perfect example of what a teacher ought to be.

Teacher-pupil relationship

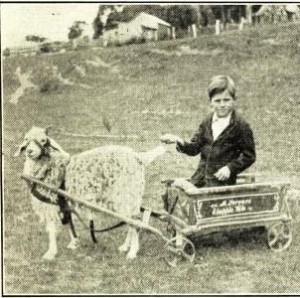

The personal teacher-pupil relationship became a hallmark of the CSV. When each new pupil enrolled, their teacher asked them to send in a photograph of themselves, their homes and pets.

‘Francis Ferrari and his Goat-Cart’ in The Mailman 1935. In possession of Virtual School Victoria. Used with permission.

The photos were placed in school albums and reflect the diverse backgrounds of these children and the human stories behind each of their young faces.

The letters were faithfully answered and returned with each corrected set of work. In an article on primary education by correspondence, the inaugural director of the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), Kenneth Cunningham, observed that

perhaps the most essential aspect of correspondence schools was in the friendly personal relationships set up between teachers, pupils and parents. … not at all uncommon for the teachers to be invited to spend their holidays at the homes of their rural pupils, and for these invitations to be accepted. (Cunningham, 1931, p.51)

An important adjunct to printed lessons was introduced in 1953 when short-wave wireless broadcasts made it possible for some pupils to hear their teachers’ voices.

World War 2 and the post-war Years 1945-69

Following the declaration of war in 1939, the CSV enrolled children under an ‘Internee’ category including those interned at Tatura in rural Victoria. The Secondary section expanded to enrol (mostly for the Leaving Certificate) Armed Services and Police Force personnel. In 1943, enrolment for correspondence school tuition became compulsory for all school age children unable to attend mainstream schools due to remoteness or disability.

In the same year, all phases of correspondence tuition were centralized at the CSV when the Infant Teachers’ Certificate (ITC) section, previously housed at Melbourne Teachers’ College, relocated to the Napier Street site. Two years later, in 1945, enrolments within the secondary section were further increased when correspondence school lessons were extended to Matriculation.

Following the Australian Government’s post-war implementation of an immigration programme from the United Kingdom and Europe, non-English speaking pupils especially challenged small rural schools where one teacher taught across many levels. During the 1950s, Mrs Ruby Burvill produced correspondence lessons for these ‘New Australian’ pupils as their teachers lacked time for individual instruction, a role the CSV would continue throughout the following decade.

The end of an era

In 1969 the CSV in Napier Street, located in Fitzroy’s housing commission area, was scheduled for demolition, and while the school was to relocate, a unique era in its history came to an end. From its humble beginnings, the school had grown into an institution which, in addition to its extensive state and interstate enrolment, had an overseas enrolment in 52 countries.

While meeting a pragmatic need, correspondence lessons did at times evoke a certain romance, as remarked by Brown in 1936, particularly when delivered to and returned from remote areas of the country using whatever means of available transport: beyond the postal van, mail was often carried by locomotive, aeroplane, bicycle, horse, bullock-cart and even occasionally by camel-train! There was an exotic element in the increasing enrolments of children in travelling circuses and other itinerant families ‘on the road’ – including at least one travelling beekeeper – interstate and overseas, in remote lighthouses, engaged in the performing arts and competitive sport, and in other situations beyond the mainstream.

Given its inspirational and ground-breaking work among children who for diverse reasons were previously excluded from an education, and the interest this created throughout the world, it may not be so far-fetched to describe as romantic the history of a school that deserves to be more widely known.

Post-script

This entry is focused on the years 1909-1969 in the school’s history when to thousands of its former students, parents and teachers it was known simply as ‘the Corro’. In the following decades the school, re-named the Distance Education Centre of Victoria (DECV) in 1994, continued to open educational opportunities for students and break down the barriers of distance.

The virtual classroom has reduced these barriers still further and even more profoundly. Reflecting these changes, from 2019 the school will be known as Virtual School Victoria, employing state-of-the-art technology to provide an engaging and inclusive learning environment for successive new generations of students in the 21st century.

The Correspondence School of Victoria, later the Distance Education Centre Victoria and now Virtual School Victoria, has a special place in Victorian education. It is a unique school whose history, that now spans more than a century, was celebrated in 2009, its centenary year. While its student population is more extensive and diverse than ever, the same principle guides the future directions of the school as in the past: to make primary and secondary education, and the opportunities that this affords, accessible to all.

Note

Material consulted includes the Archive Collection of Virtual School Victoria; Public Record Office of Victoria (PROV), VA 714 Education Department, VPRS 10537/PO Units 4-10, Correspondence School: Primary, 1939-1969; Units 11-14, Correspondence School: Secondary, 1933-1969.