During the deadly pandemic that killed more than 9000 people in New Zealand and as many as 50 million people world-wide, Catholic teaching orders turned their focus to ministering to the sick. Schools across the country were closed from November 1918 to February 1919. Released from their teaching duties Catholic sisters, with the assistance of teaching brothers, priests and local volunteers, cared for victims of the pandemic from all sections of the community. At a time when new schools were being built to house the rapidly expanding number of Catholic pupils, many were found to be suitable as temporary hospital wards. Catholic Sisters, some from enclosed congregations, ran these hospitals. They also went out into city, town and rural communities to assist families suffering from the pandemic. Until now the work of Catholic Sisters during the 1918 flu pandemic has been largely unrecognized. The first to volunteer, for six weeks from early November 1918 they nursed the sick and dying from all sections of society.

Origins of the pandemic

There is evidence that the mild first wave of what became known as the ‘Spanish Flu’ originated in North America in January 1918. A second more devastating outbreak reached New Zealand in late October 1918. During the pandemic, New Zealand lost about half as many people to influenza as it had over the four years of the First World War. The overall rate of death for Europeans in New Zealand was 5.8 per thousand people. But in some communities the death rate was well above the national average. Māori communities were badly affected, with about 50 deaths per thousand people, eight times that of Europeans. In one community in the Waikato, Mangatāwhiri, about 50 out of 200 local Māori died. However, the most dangerous places to be in 1918 were military camps. For young soldiers living in the Featherston and Trentham camps, rates were 22.6 and 23.5 deaths per thousand respectively. Some small towns and rural communities were badly affected. In the coal mining district of Nightcaps and Wairio in western Southland the death rate of 45.9 per thousand people rivalled that of many Māori communities.

Auckland: Schools become emergency hospitals

All the schools of the Auckland Education Board were closed on 7 November, and remained closed until the new year. For thousands of schoolchildren, many of whom were nursing sick family members, the summer holidays came early. Standard Six pupils were awarded certificates of proficiency on the basis of inspectors’ reports and school records instead of by examination, and examinations for public service entrance and senior free places, due to be held in November, were postponed. University examinations began as usual on 7 November and proceeded until one student died of the flu, after which they too were suspended. By early November hospitals in Auckland were full to bursting with large numbers of doctors and nurses down with the influenza. Henry Cleary, Catholic Bishop of Auckland, who had been a chaplain in the Flanders trenches during the severe winter of 1916-17, offered the two Vermont Street Schools in Ponsonby to the Health Department as a temporary 100-bed hospital under the charge of the Sisters of Mercy. It became the second emergency hospital in Auckland; the other major hospital being at the Seddon Memorial Technical College in Wellesley Street. Elsewhere in the city smaller temporary hospitals were set up in halls or schools at Northcote, Takapuna, New Lynn, Otahuhu, Manurewa and Papakura.

Sisters of Mercy and Officials at Vermont Street Emergency Hospital November 1918.

Back Row: Sister M Gonzales, Nurse (unknown), Sisters M Felicitas, M de Pazzi (matron), and M Madeleine.

Second Row: Sisters M Ursula, M Bernadine, Mother M Josephine, M Francis, M Aquin, M Callistus, M Elizabeth, Rev Brother Fergus.

Front row: Rev Brother Callixtus, Rev Father Carran (parish priest), Dr E H Maguire, Mr William Wallace, Rt Rev. Bishop W Cleary, Sir Carrick Robertson (superintendent), Mr M J Coyle, Rev Father Hunt.

Photo courtesy of the Sisters of Mercy, Auckland.

Sister de Pazzi McAlister and Sister Agatha Regan, both trained nurses, came from the Mater Misericordia Hospital to set up the emergency hospital. The Mater hospital was itself so full at one point that its chapel was converted into a temporary influenza ward. Sister de Pazzi had faced the daunting conditions of an epidemic before, having nursed during the 1900 outbreak of bubonic plague in Sydney. Fellow sisters from around Auckland joined her. Most were teachers from convent schools closed for the duration of the pandemic. Although they lacked nursing training they dressed in white gowns and masks and treated the stricken men who were the first flu victims. As the numbers of sick increased, convalescent patients transferred to St Joseph’s School in nearby Grey Lynn where they were looked after by Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart.[1] During the six weeks of the pandemic at least 254 patients from all walks of life were treated at the Vermont Street Hospital; 85 patients died there. Senior boys from the Brothers’ school served as messengers and orderlies. Sister Gonzales McKendry and Brother Fergus Gilbert, a Marist Brother, set up a morgue in the cellar of the school for the many bodies awaiting transfer for burial. Several Sisters of Mercy, including Sister De Pazzi, contracted the flu virus. Fortunately, they recovered. However, Sister Teresa Norbet, a Sister of St Joseph, died after nursing patients at the Grey Lynn school. By the end of the pandemic 1,128 had died in the Auckland city area, a rate of 7.6 per thousand.

Wellington: Teacher volunteers and victims

Wellington had some advantages over other cities in New Zealand. Being the capital city, the head office of the health department was located there. It also had a large modern hospital and a high ratio of doctors to population. In reality, however, Wellington was a dangerous place during the 1918 pandemic. Political wrangling aggravated organizational delays; many doctors caught the flu; and relief efforts suffered from a chronic lack of voluntary helpers. By 12 November, when cheering crowds spontaneously thronged city streets in celebration of the Armistice, Wellington was firmly in the grip of the pandemic. The Alexandra Hall in Abel Smith Street and the Soldiers’ Club in Sydney Street were equipped with army beds by the Defence Department and staffed by women of the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) and the Women’s National Reserve, some of whom were trained nurses. Both halls quickly reached capacity. The Mayor, Sir John Luke, called for volunteers to nurse the sick and announced the opening of a depot at the Town Hall for free medical supplies. Sisters from the Home of Compassion Island Bay responded to the call, nursing the sick in the southern and eastern suburbs. The local Vigilance Committee assigned a motor-cyclist with side-car for Sister Clotilde Webber, who was in charge of the 15 Sisters who had volunteered to nurse in the community, most of whom were St John’s Ambulance medalists. She also had a couple of Boy Scouts in attendance to carry messages to the depot, or to her Sisters.

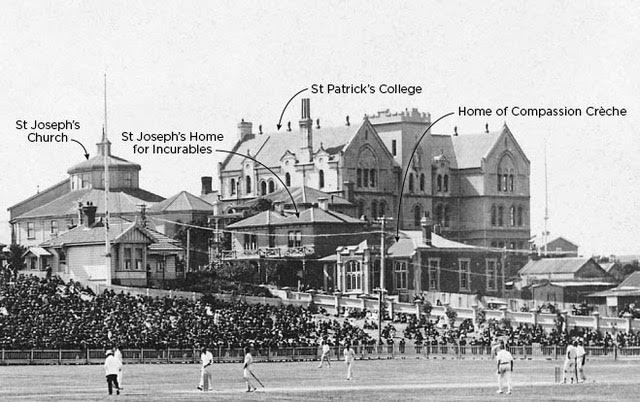

St Patricks College Wellington, 1930s. The Catholic precinct around Buckle and Tory streets, as seen from the Basin Reserve. The Home of Compassion is the only remaining building. Source: https://mch.govt.nz/pukeahu/park/significant-sites/home-compassion-creche

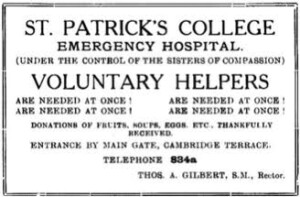

As soon as the schools closed on 11 November, Father Thomas Gilbert s.m., the Rector of St Patrick’s College, a secondary school run by the Marist Fathers, offered the college to the Health Department with the proviso that it be run by the Sisters of Compassion. Father MacDonnell s.m. supervised provisioning and a student, William Carmine, acted as secretary. Sister Genevieve Sexton was appointed matron. She and a team of 18 volunteers, including sisters and volunteers from the community, cared for 91 men from all denominations. Dr Kingston-Fyffe, the attending doctor, described the hospital as ‘a model of good management and good nursing in contrast to the chaos at the other temporary hospitals’ (Blue Note, November 1918). While the Sisters were involved in epidemic work, they were fed by their colleagues at the Sacred Heart Convent who sent over enough hot meat and potatoes for 24 people each day. The people of Island Bay also gave generously. Unfortunately, 21 Sisters of Compassion came down with the flu. When the sick sisters were convalescing, the Sisters of the Sacred Heart insisted on taking them in groups of 6 to 8 at a time to help them recuperate.

Poster for Emergency Hospital Volunteers, Nov 1918.

Source: Blue and White Magazine, St Patrick’s Wellington, November 1918, p. 64. http://classorama.com/schools/stpatstown/1918/1918_073.jpg

On 21 November the Sisters of Mercy opened a hospital at St Anne’s parish hall Newtown to accommodate seamen who were convalescing from influenza. Sister Aloysius, assisted by a team of local volunteers including senior girls from convent schools, looked after about 48 patients. They also assisted sick families throughout Wellington, Petone and the Hutt areas, as did the St Vincent de Paul Society and local clergy.

Sister volunteers risked their lives to help the sick. Many fell sick and two Wellington Sisters died after contracting influenza. Each day Chanel Burton, a Sister of Mercy and Superior of St Catherine’s Convent Kilbirnie, walked more than three kilometres to the St Patrick’s College hospital where she was a volunteer. On 30 November after a particularly busy day nursing, she called at the Newtown convent on her way back to Kilbirnie. The superior noted how sick she looked and suggested she stay overnight. However, Sister Chanel said she had to pick up some medical supplies in Kilbirnie and intended to return to the hospital to keep vigil with a patient. After walking to Kilbirnie she went to her room to rest. When she did not return to the community room the sisters went to her room to find that she had died. In 1919 the newly built St Catherine’s College became her memorial. Although Natalie O’Meara, a Sister of Compassion, was a nurse, she did not attend the victims of the epidemic, as she and her novices were in charge of the Nursery at the Home of Compassion and precautions had been taken to isolate the babies. Sister Natalie probably caught influenza while visiting her brother who had a severe case. She died on 13 December 1918. Over the course of the pandemic, 757 people died of influenza in Wellington, a rate of 7.9 per thousand.

The Southern cities: Boarding schools become wards

Although health authorities in Christchurch were aware of the development of flu in the North Island by early November, Christchurch’s Carnival Week celebrations went ahead. Large numbers of visitors from out of town attended the races and the agricultural show including visitors from the North Island. Friday 8 November was People’s Day. That day was also known as the ‘false armistice’ and many people gathered to mark the end of the First World War even though the official Armistice announcement occurred on 12 November. The celebrations helped the flu spread through the city and on to other towns and regions. Shops, offices and factories shut down and schools, hotels and theatres were closed by order of the government. Because shipping from port to port around New Zealand came to a halt, cities like Christchurch suffered from a shortage of basic supplies, such as flour and coal. In some places it became impossible to hold proper funeral services for the victims of the influenza. By November 14, Christchurch Hospital had 145 flu admissions. Serious cases in the city were directed to the public hospital and over half the city’s deaths from flu occurred there. Seven hundred and twenty two patients were admitted during the epidemic of whom 232 died. The city launched a relief organization and the legendary Nurse Sibylla Maude, a pioneer of district nursing, set up a relief depot in Cathedral Square. As many nurses were ill with the flu, Nurse Maude appealed for volunteers and in the early days it was Catholic Sisters who did most of the arduous night work.

Emergency hospitals were set up to cope with the overflow from the public hospital. The Little Company of Mary, known as ‘the Blue Sisters’, offered Lewisham, their 40-bed hospital, and the Royal Hotel was also used. The sisters rigged up a tarpaulin over the hospital balcony, slept there and converted their rooms for patients. Nine sisters, more than half the community, caught the infection. Sister Frederick Reynolds died. To keep the hospital going, Sisters of Mercy, Mission Sisters and Marist Brothers came to help. At one point the Marist Fathers took over the admission of patients. Fortunately, organizations such as the Automobile Association, Boy Scouts and St John Ambulance Brigade provided volunteers. The Sisters of Mercy, Mission Sisters and the Marist Brothers also worked under the leadership of Nurse Maude in the public hospital as well as private hospitals, the Sanitorium and private homes. Twenty Mission Sisters caught influenza. By the end of the pandemic 458 people had died, a rate of 4.9 per thousand.

The first influenza death in Dunedin occurred on 4 November. Despite official warnings to avoid ‘crowded assemblages of any kind’, the citizens of Dunedin also insisted on celebrating the Armistice in grand style, with speeches in front of the town hall, singing and brass bands playing in the Octagon. By 13 November schools, libraries and theatres were closed and Dunedin hospital was overflowing. The first auxiliary hospital in Dunedin was in the Sunday school hall (known as Stuart Hall) attached to Knox Church. It was a fairly new brick building with kitchen and toilet facilities, and was only a block away from the main hospital. Fifty beds were set up here in the days following the Armistice. A convalescent ward was opened later in November in the Hanover Street Baptist Hall, with accommodation for forty. Thirty-three nurses were infected. With nursing facilities in the city stretched to the limit, the Sisters of Mercy across the city began caring for influenza victims in their homes leaving the convent early in the morning and returning each evening. They set up part of the boarding school in South Dunedin as an infirmary and nursed many of the sick there. They set up a crèche at St Patrick’s School to look after children whose parents were unwell. On 22 November — the day Dunedin’s Catholic Bishop, Michael Verdon, died of influenza — Dunedin Hospital wards were crammed with 247 influenza cases, including 4 of its 5 surgeons and 82 of its 116 nurses. By the end of the pandemic, 273 people had died, a relatively low rate of 3.9 per thousand when compared to other cities.

Māori communities: New schools as hospitals

Māori communities across the country were hit hard. The experience in Panguru, a small town in Hokianga in the Far North, is representative. Whina Cooper, who later received the Aotearoa New Zealand Order of Merit for her work as foundation president of the Maori Women’s Welfare League and leader of the 1975 Land March to Parliament, remembered that people were dying on the side of the road with no one to help. Her own father was the first to die. The Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, who had just arrived in the community, turned their new school into a hospital. Sister Sixtus French recalled the sisters making soup and nourishing drinks for patients in the hospital and taking it around the whares. Local Maori provided meat and vegetables. Eight people died in the school hospital and two sisters came down with influenza. In the Hokianga area 158 Maori died in a population of 3,829, a rate of 41.2 per thousand.

Beyond the cities: Sister volunteers in the community

In towns and country areas, the fight against the flu was waged on a smaller scale and with fewer resources. Without proper hospitals the communities relied on local volunteers and a scattering of doctors who might be reduced to one or two if others caught the flu. Catholic teaching orders had established parish schools in small towns and rural areas across the country. It was these teaching Sisters who volunteered to nurse victims of the influenza. The Sisters of Mercy, being by far the largest teaching order, had schools and convents across the North and South Islands. In the South Island they set up temporary hospital wards in parish and boarding schools in small towns such as Gore, Riverton and Greymouth; patients were transferred there from the local hospitals. In Mosgiel they cared for the sick in their own homes. In Marlborough, Sisters of Mercy looked after children while their parents were unwell and in Blenheim they took over nursing duties at Wairau Hospital when the Matron and her whole staff were sick. A number of Sisters of Mercy contracted influenza and Sister Lawrence Whelan, who had taken charge of the hospital at Te Aroha, died on 2 December.

Even semi-enclosed congregations, such as the Dominican Sisters, went from door to door caring for the sick. Each morning for a month Mother Gonzales Wall and Sister Mechtilde Mace from Teschemakers College near Oamaru went out to Maheno. They moved from house to house cooking meals, washing patients and making beds before being driven home at the end of the day, changing their clothes in a farm building and going straight to bed.

The Sisters of St Joseph, who had a number of parish schools in Canterbury and Otago, assisted in the small local hospitals. In Morven they came from the convent to do night duty and relieve local women who had been looking after patients during the day. In Temuka they nursed at the Presbyterian Sunday School Hall, which had been turned into a temporary hospital. The Sisters also visited the homes of those affected by influenza. Stella Goodman, who was a child at the time, remembered ‘how wonderful the nuns from St Joseph’s were’ and that they were the only ones who would nurse some of the ‘old timers’ who came to the hospital from the ‘unhygienic sod houses’ on the east side of the town (Rice, 2005).

The Mission Sisters had a number of schools in the Canterbury area. During the pandemic they assisted families in the community. When the epidemic broke out in Kaikoura, Mother Theophane McKain and Sister Leocritie Duggan went out to nurse the Garrett family who had fallen ill and had no one to attend them. For a week they nursed the family before they both caught the infection. Mother Theophane died on 3 December.[2] The situation in the North Island was similar. Here the Mission Sisters had schools in small towns in Taranaki, Waikato, Auckland, Hawkes Bay and Wellington. Their experience in Hamilton was typical. In this case all their pupils were taken ill. It was impossible to send them home as many lived in places where influenza was raging so the Sisters looked after them at the school and convent. At the same time the flu was spreading in Hamilton with whole families sick. Each day the sisters went into the town to offer assistance to anyone who needed help. They also took in three pneumonia patients who could not get places in the public hospital. Eventually three of the sisters were infected and Mother St Theodosia Commons, who had been nursing the children, was taken very ill on 11 November. Fortunately, she recovered.

Mother Theophane McKain rndm (Religious de Notre Dame Missions)

Photo courtesy of the Sisters of the Mission Archives New Zealand

The Sisters of St Joseph had schools and convents in the regional areas across the North Island: Northland, Auckland, Waikato, Hawkes Bay, Bay of Plenty, Taranaki, Coromandel and Wellington. In Hastings, Sister Thecla McLoughlin of the Sisters of St Joseph of Nazareth cared for many children in the community whose parents were unwell. She became ill and died on 7 December. The Brigidine Sisters had a school in Masterton. During the epidemic they turned their classrooms at St Brides into wards for those convalescing from the ‘Black Flu’.

Conclusion

Many Catholic sisters caught the flu as a result of nursing the sick. Newspaper accounts of the time and convent records suggest the numbers are likely to be in the hundreds. Current research suggests that eight sisters died of influenza. Most were young women. The loss of eight young Catholic Sisters would have been traumatic for their communities. Convent records note the long-term effects of the flu on the health of some of their sisters. Some mention a sister’s service during the pandemic, particularly if she died. But in line with contemporary attitudes to service that subsumed an individual sister’s identity and actions within notions of sacrifice and self-abnegation, sisters’ graves generally record just a name and date of death. Some local communities acknowledged the sisters’ efforts. In Auckland the Sisters of the Mission were granted free bus passes as a gesture of thanks for their efforts. The Kaikoura community erected a marble cross acknowledging the life of Mother Theophane. The inscription is simple: ‘pray for the soul of Mother Mary St Theophane who died on December 3rd 1918’ (Kaikoura public cemetery). And Māori communities have long memories; Panguru recently celebrated the special relationship with the Sisters of St Joseph that began more than 100 years ago during the pandemic.

Compared with the Covid 19 pandemic of 2020, the 1918 influenza pandemic was relatively short-lived. However, the loss of more than 9,000 people had long term effects on the New Zealand community particularly on the children of those who died. School children were less vulnerable to the influenza virus than adults, but many were adversely affected when their parents died or became very ill: 6,415 children lost one parent and 135 lost both. Catholic sisters ran creches for these children in their schools. After the pandemic a number of pupils who had lost their parents remained in the care of the sisters until relatives came to claim them; some lived with the sisters for many years. By mid-December life had largely returned to normal. In February 1919 the schools re-opened and the sisters returned to their roles as teachers. Over the years accounts of the work of Catholic sisters during the 1918 flu pandemic have slipped from historical memory.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Sister Archivists in the following archives who provided invaluable assistance during the Covid19 pandemic lockdowns at a time when it was difficult to physically access archival resources: Sisters of Compassion Wellington, Sisters of Mercy Auckland and Wellington, Mission Sisters New Zealand, Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart Aotearoa New Zealand, Dominican Sisters Dunedin, the Little Company of Mary, Christchurch.

Notes

[1] The Sisters of Saint Joseph of the Sacred Heart (founded by Mary MacKillop and Rev. Julian Tennison Woods) established two congregations in New Zealand, the Sisters of St Joseph of Nazareth in Whanganui (1880) in the North Island and the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart (1883) in Temuka in the South Island. They merged in 2012. https://www.sosj.org.au/about-the-sisters/history/

[2] Mother Theophane was born Alice May McKain in Napier in 1863, the sixth of nine children of James and Sarah McKain. A convert to Catholicism, Alice joined the Sisters of the Mission in Nelson aged 18 years. She was a primary school teacher in Christchurch from 1889 until 1915 when she moved to Kaikoura as Prioress and Head teacher. She died of influenza on 3 December 1918.