Gwen Somerset was a well-known New Zealand educationalist in adult and early childhood education. The daughter of Clara Buckingham and Frederick Alley, Gwen was born in 1894 in Canterbury. She trained as a primary school teacher as well as studying at Canterbury College (now the University of Canterbury), and spent almost 17 years as Infant Mistress at Oxford, a small rural town in Canterbury.

Gwen married her long-time friend and fellow teacher Crawford Somerset in 1930, and they had two boys. During their time in Oxford, the Somersets were enthusiastically involved in adult education in the local community. They were awarded a joint Carnegie Fellowship and in 1936 they travelled overseas, being exposed to the latest in progressive education, adult education and nursery schools.

A year after their return, they were invited to Feilding, a provincial town in the North Island, to run the new Community Centre. Gwen was now 42 years old, an experienced teacher and parent. The community centre quickly became the centre of adult education in Feilding. Gwen started a child study class for parents alongside a children’s play group and in 1944 this group became a Nursery Play Centre, connected with the fledgling organisation that had started in Wellington (today known more simply as Playcentre).

Soon after the war years, in 1947, the Somersets moved to Wellington where Crawford took up a position as a lecturer at Victoria University. Gwen officially retired from teaching, but quickly became involved in many national organisations. She became the first President of the New Zealand Federation of Nursery Play Centres in 1948 and then continued as Dominion Advisor until 1969. She was also a member of the Wellington Regional Council of Adult Education and the Wellington Free Kindergarten Education Committee. In these roles and others over the next forty years, she had a profound influence on early childhood education in the Wellington region, and through her prolific writings on early childhood and adult education, throughout the country. Gwen died in 1988, shortly before her 94th birthday.

Her philosophy of education

Somerset as progressive educator

Over the course of her career, Gwen developed a philosophy of child-centred, play-based education for young children. This philosophy was influenced by her rural childhood which allowed plenty of free play in the countryside, and also by her school teacher father. Frederick Alley had been an advocate of ‘learning by doing’ and was well acquainted with educational theorists who promoted child-centred activity learning, although he was constrained by the education system of the late 19th and early 20th century. Gwen recalls him saying to her sadly “Father Pestalozzi might never have existed” (Somerset & Morton, 1988, p. 26). Later as a pupil teacher, Gwen was herself saddened by the standard pedagogy she observed being practised; much rote learning of isolated and often irrelevant facts, repetition of rote answers as a means of assessment, enforced inactivity and excessive use of physical punishment as a means of both discipline and motivation. She recalls that in 1914:

On my first morning, I found two rows of new entrants of five years seated on two forms facing each other beneath the blackboard. The room was deathly quiet except for the occasional squeak of a pencil on a slate. The two rows of new children sat quivering in fear of the strange world into which they had just been deposited. The Infant Mistress loomed above them. She announced, “The first one who cries will get this,” and showed her strap. I was to stand on guard hoping they would all be able to gulp down the threatening sobs. I dared not show sympathy in case of reaction. I just stood and prayed hard and swallowed my own tears. (Somerset & Morton, 1988, p. 105)

Teachers’ training college in the 1910s was inspirational for Gwen, and here she was exposed to New Education ideas, and academics and fellow students who shared her developing ideas on child-centred pedagogy and the value of a broad liberal arts curriculum based on relevance to children’s lives. A significant event for her was attendance at the first Workers’ Educational Association (W.E.A.) Summer School, held in Oxford in 1920, with lectures and workshops from key figures such as New Zealand’s first Professor of Education, James Shelley. These formative experiences combined with her creative disposition to produce educational innovations in a variety of settings over her teaching career.

In 1921 Gwen moved to the small rural town of Oxford and took up the position of Infant Mistress, and was then able to try out her ideas on teaching young children. She believed in the value of creative expression as a means of learning:

With two young assistants just out of Teachers’ College, we had 100 new entrants in our care. We arranged an interlocking activity programme, agreed on a common approach to discipline, we danced and sang and built and painted and explored the countryside. (Somerset, 1989, pp. 9–10)

But what did these children need? Lively music and movement and lots of creative work to gain skills, loosen limbs and fingers, and relieve tension. (Somerset & Morton, 1988, p. 142)

When a new consolidated school was opened at Oxford, Gwen and her assistant teachers moved into an ‘open air’ classroom (a classroom with wide windows, plenty of light, and easy access to the outdoor environment), which was a popular innovation of the 1920s to encourage better health amongst the children.

Infant classroom, Oxford School, ca 1930s. Oxford Historical Society collection, Canterbury Museum, 1991.144.3. Permission of Canterbury Museum must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

Her goals for children’s education were related to a view of the value of a liberal education for all ages, and especially in a rural environment: education was to broaden a person’s thinking and allow for other possibilities in a community constrained by tradition and close-knit, hierarchical networks of relationships. To broaden children’s thinking required parents to be involved:

I believed that education should be equally the responsibility of the school and the home and that little of lasting value was gained either by the individual or by society unless there was a continual feed-back from home to school. (Somerset, 1972, p. 4)

Gwen started to experiment with ways of getting the parents to be more involved. One of the more successful ideas were ‘school visits’ where younger siblings who came with their mothers to town on market days spent the afternoon as ‘guests’ of the 5-year-olds. This was primarily to help the younger children’s transition to school when the time came, but had the added bonus of allowing relaxed discussion with the mothers at pick up time.

Along with her husband Crawford, Gwen also developed an approach to adult education that had a similar philosophy: education needed to be connected to a person’s home life and interests, and should involve experiential learning backed up with theory. She reflected on her developing ideas:

It became clear that the starting point for adult education was in a person’s first community, the home. … We had begun to see adult education, not as a series of classes offering certain topics and separated into subject matter, a “what-are-you-taking-this-year” approach, but more as an experience in relationships, an education in living rather than as an “education for life”, not what is offered but how it is offered, and how shared. (Somerset, 1972, p. 17)

In 1936 Gwen and Crawford Somerset spent the year travelling abroad courtesy of a Carnegie Fellowship. This year included attendance at the first World Conference in Early Childhood Education, visits to British Nursery Schools, Danish Folk High Schools and the New York Bureau of Educational Experiments. They met many people involved in progressive education and also the New Education Fellowship (NEF). However, Gwen found that in all the innovative and world famous early childhood ventures they visited, the “main objective seemed to be ‘to take children from the harmful influence of parents’” (Somerset, 1989, p. 10) and she did not find “what I felt was needed by the ordinary parents with a young and growing family. Understanding of the social, emotional and intellectual growth of their children was surely the most urgent need of young parents, along with Plunket feeding schedules” (Somerset & Morgan, 1988, p. 191). For Gwen, the overseas trip affirmed her philosophy of educating the parent alongside the child.

Gwen as a Parent Educator

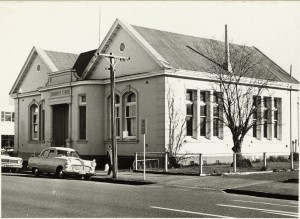

Feilding Community Centre. Photo by Manawatu Standard, provided by Palmerston North City Library Photograph Collection, 2011p_fe17_004568.

Moving to Feilding in 1938 marked a transition for Gwen from being an Infant teacher who was also involved in adult education, to being primarily an adult educator. With her interest in young children and her exposure to the latest international ideas on Nursery Schools, it was natural that some of her adult education gravitated towards providing support and education for parents of young children. This started with young mothers approaching Gwen for advice, generally about the same range of topics. It struck Gwen that the mothers’ talks revolved around problems, and the joys of watching children develop was often overlooked. She felt that:

There was a need for practical experience with a group of young children where their early development through free, spontaneous activity (or play) could be observed and shared by parents. I soon realised that discussions should follow experience in a playgroup, not precede it. (Somerset, 1989, p. 11)

The Nursery School opened in September 1938 with a roll of 17 children, rapidly growing to 35 children by the end of the year. The weekly playgroup including a study class for the parents and monthly meetings were held to manage the business of the Nursery School. Her model of parent education therefore was one where theoretical learning took place alongside practical experience of children’s play, in a collaborative setting. For the children’s education, she continued to advocate for the value of play and its physical and psychological benefits.

Gwen as a Playcentre educator

Nursery Play Centres started in Wellington in 1941, with Beatrice Beeby (the wife of C.E. Beeby, Director General of Education) as one of the founding members. This parent co-operative movement was designed to provide some leisure time for mothers during World War II, while the men were away on service. When Beatrice was invited as a guest speaker for a monthly meeting of the Feilding Nursery School, she observed the involvement of mothers in the playgroup and commented that this was operating as a Nursery Play Centre. Gwen immediately changed the name of the group, and the Feilding Nursery Play Centre became affiliated with the new organisation – although for several years there was not much contact.

Children at Kelburn Playcentre c 1950. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23193939

Crawford Somerset was appointed as a lecturer at Victoria University of Wellington in 1947. When the Somersets moved to Wellington, Gwen did not seek a paid teaching position, instead intending to pursue her interest in art. However, thanks to her contacts such as Beatrice Beeby, she was quickly involved in adult education on a voluntary basis. When the Nursery Play Centre Federation was formed in 1948, she was asked to be its first President, a role that she held for four years. Following from this she was Dominion Advisor and Editor of the Nursery Play Centre Newsletter (now the Playcentre Journal) until 1969. In these roles and others such as being a member of the Wellington Free Kindergarten Education Committee, she was able to influence the direction of early childhood education both in Wellington and nationally.

The Nursery Play Centre Association had started in 1945 offering lecture courses by Beatrice Beeby for parents to prepare them for supervising sessions. After Gwen became President of the new Federation in 1948, parent education became more systematic and incorporated more fully into the organisation’s philosophy. Gwen’s well-known metaphor likened child and parent education to the wings of a butterfly: both must work together to allow the butterfly to fly. She considered that teachers should approach the parent and child together as an educational unit. Her view was that parents are best supported by being taught about child development and the value of play, and this could be achieved through a combination of education by ‘experts’ and practical experience with children in a rich play-based setting, again guided by more experienced ‘experts’. Over time this philosophy was challenged by Lex Grey, who believed that ‘experts’ were not required, and that parents could learn all they needed to by observing children and participating together with other parents in a cooperative manner. Both philosophies can be seen in the Playcentre of the early 21st century.

Gwen’s Influence on the early childhood sector

Much of Gwen’s national influence, and influence on early childhood outside of Playcentre, was due to her prolific writing. Her initial text for new Playcentre members, I Play and I Grow (1949), was used to set standards within Playcentres. It was the first book published by the Playcentre Federation, and at the time it was one of the few early childhood education resources available in Aotearoa New Zealand. Other books that were well-used both within Playcentre and in the wider early childhood sector were Work and Play (1958) and Vital Play in Early Childhood (1976), both showing her emphasis on play as the medium of education for young children.

In her role as Dominion Advisor and through these texts, Gwen influenced Playcentre to incorporate ‘free play’ into its philosophy; through her membership of the Education committee she influenced the Wellington Free Kindergartens to ‘go free’; and when Moira Gallagher was appointed as the first pre-school officer for the Department of Education with an unofficial “brief … to ‘free up the kindergartens’” (May, 2009, p. 18) she issued I Play and I Grow as a departmental text. This move towards free play in the early childhood sector was radical at the time, but has since become mainstream, as evidenced by the play-based philosophy of the Aotearoa New Zealand early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki.

To achieve her goal of ‘free play’ in early childhood, Gwen promoted a quality play environment. She started work on a minimum equipment list to “encourage a higher standard of activity equipment in all pre-schools” (Somerset & Morton, 1988, p. 209), and described appropriate equipment in her texts, as well as guidance on how adults should interact with children in these play areas. It was Gwen who introduced Caroline Pratt’s multiple unit blocks to the early childhood sector, from measurements taken when Gwen visited the Bureau of Educational Experiments in New York in 1937.

As a mother who continued teaching after she had children, Gwen was not afraid to challenge accepted ideas of motherhood. Her educational philosophy was not aimed at freeing women up from the task of child rearing. She was concerned with educating young children to become emotionally and intellectually stable members of adult society, and believed this required also educating their parents. She accepted, rather than challenged, women’s predominant role as the primary caregiver. Her contribution to feminism was less about promoting early childhood education as a means to give women some leisure time (one of the earliest aims of Playcentre) and more about assigning value to the child-rearing role. She saw women as the best educators of their children, and set about supporting them to do this. When ideas of bonding and attachment became popular in the 1950s, she and Playcentre aligned themselves with these ideas. Over time attachment theory has evolved to become less dogmatic and restrictive for mothers, but the concept of parents spending time with their children is still strong within Playcentre philosophy today.

Conclusion

Gwen Somerset was a product of the New Education and Progressive Education reform movements of the early 20th century. She promoted child-centred, activity-based education for young children. Her contribution to early childhood education in Aotearoa New Zealand was to promote the value of a play-based pedagogy, to create an expectation of high standards in equipment for early childhood centres, provide written resources at a time when they were severely lacking, and most of all, to advocate for the parent and child to be educated together. Playcentre has evolved into an organisation that emphasises both children’s education and parents’ education, largely as a result of Gwen Somerset’s influence as an infant teacher and adult educator.