The New South Wales Teachers Federation has, over its one-hundred-year history, operated in two major roles, industrial and professional. As an industrial trade union it has concerned itself with teachers’ salaries, working conditions, and staffing of public education institutions. As a professional body it has endorsed and campaigned for a wide range of matters related to teaching and learning. Many members, both present and past, would include a third role, this being working “to construct a better world” (Fitzgerald, 2011, p. 295) through its support of social, political and economic causes, often controversial, and an ongoing support for social justice. The Federation has been and continues to be a strong union, with large percentages of the teaching workforce being members. It has had a profound influence upon schools and schooling, teaching and the teaching profession in New South Wales.

Formation

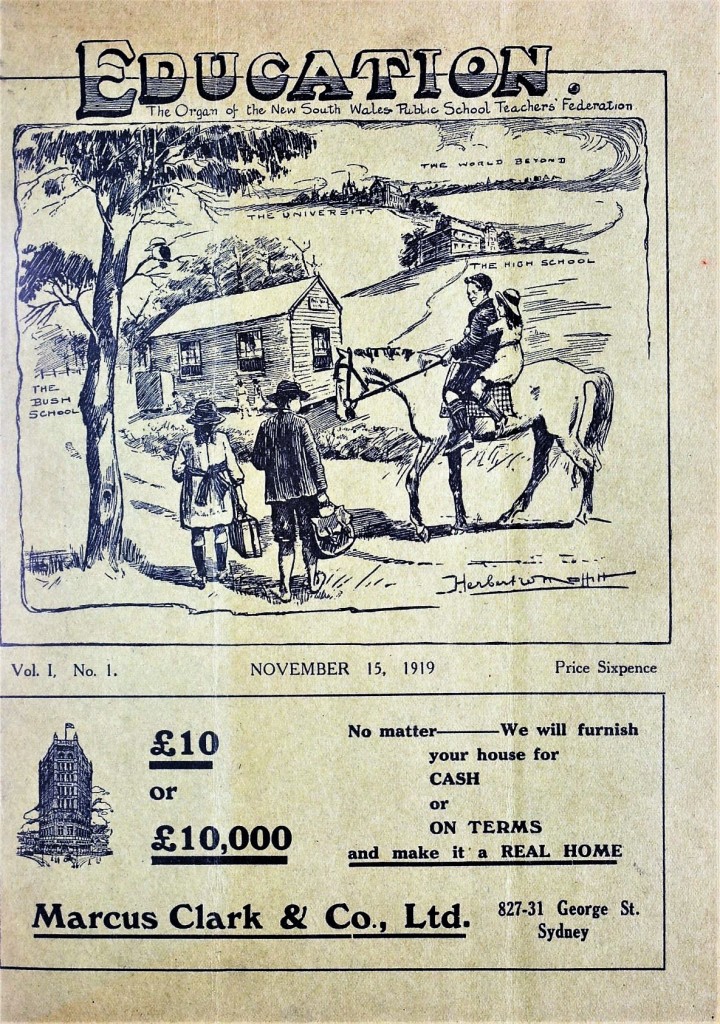

The New South Wales Public School Teachers’ Federation was founded on 26 September 1918 when the Public School Teachers’ Association of New South Wales (operating since 1898) combined with several smaller associations including the Assistant Teachers’ Association, Women Teachers’ Association, and Headmasters’ Association. Unlike the Association, the Federation would be a registered trade union which could negotiate teachers’ salaries through the arbitration courts. This followed frustration with the previous system of direct negotiation with the Department of Education and the doubtful promises of politicians. Like the earlier Association, the Federation would continue to hold an annual conference to bring teachers together to discuss and pass resolutions relating to education. In 1919, the Industrial Arbitration (Amendment) Act (Act no. 50, 1919) allowed access to arbitration for public servants. The Federation elected its first executive in March 1919, set up working committees, launched the first issue of its monthly journal, Education, in November and held its first Annual Conference in December 1919. By the end of 1920, six thousand teachers had joined the Federation; this representing about 75 per cent of public school teachers (Mitchell, 1975, p. 50).

Between the Wars: 1920s and 1930s

High membership allowed the Federation to thrive. In the 1920s, achievements included new salary awards in 1920 and 1927. The Federation comprised a number of Sectional as well as Country Associations. Sectional Associations included the influential Assistant Teachers and Women Assistants, the growing Secondary Teachers, Headmasters, Men First Assistants, Women First Assistants, Girls’ Mistresses, Infants’ Mistresses, Technical, Ex-students, and Isolated. In addition, there were clubs and societies allowing for various interests. Constitutionally the Federation could not become involved in party politics, and obviously its membership was drawn from all political parties, but even in the 1920s historians note a pro-Labor stance of active members. Overall, relations with the Department of Education remained co-operative, with Federation activity including the writing of letters, discussions and deputations.

Education illustrates the ideal that every state school-child had the opportunity to proceed to higher education.

The journal Education styled itself as an organ for teachers: written by teachers, in the interests of teachers, and its pages open to all (December 1919, p. 46). Through the journal, teachers were able to take an interest in salaries, teaching conditions, and educational issues more generally. Education reported Federation meetings at all levels, the annual conference, and industrial activity. Early issues indicate a time of hope when teachers looked towards the extension of reforms achieved in New South Wales after 1904. The War was over, a revised syllabus for primary schools was scheduled for introduction in 1922, secondary school education was expanding, and well-appointed new schools opening.

Editorials and contributed articles optimistically addressed future desired reforms. These included reduced class sizes, new equipment, adequate accommodation, increased public awareness, provision for pre-school education and the education of physically handicapped and “mentally defective” children. Articles describing progressive new methods, such as Montessori, the Dalton Plan and the Project Method, were frequent. The visit of English educationalist John Adams, in 1924, was reported and his lectures reproduced. As the decade progressed, however, the journal indicates a shift in tone as teachers realised that progress in the desired reforms was either painfully slow or non-existent.

Economic depression in 1929 and the early 1930s saw the restriction of government expenditure on education. The Public Service (Salaries Reduction) Act (1930) led to loss of income for teachers and occasioned protracted campaigning on the part of the Federation in the mid-1930s to restore salaries. The Married Women (Lecturers and Teachers) Dismissal Act (1932) meant that married women no longer had security of employment, with many losing their jobs and all subject to annual re-appointment. It would be fifteen years and much agitating before this Act was repealed (Theobald and Dwyer, 1999). Non-appointment of hundreds of Teachers’ College graduates during the Depression was also of great concern. The Depression exacerbated problems of large class sizes, the shortage of teachers, and poor physical conditions of schools.

In the early 1930s some of the more radical Assistants, frustrated with the Federation’s conservative leadership, formed the Educational Workers League. The League remained small but active and publicised its ideas through a journal, The Educational Worker. The group included communist Sam Lewis, later President of the Teachers Federation. In 1936, the League disbanded when its members became more influential within the Federation itself. After a decline in membership in the early 30s, the Federation again attracted 75 per cent of public school teachers by 1939.

The Federation, in the later 1930s, turned its attention to issues of educational reform. It supported the organisation of the Sydney session of the New Education Fellowship Conference held in 1937. This event was attended by thousands of teachers and attracted wide press coverage and public interest. In June1938, the Federation organised its own public conference, “Education for a Progressive, Democratic Australia”, which was attended by representatives from hundreds of organisations, and which passed many resolutions for specific and wide-ranging educational change. The abolition of the Primary Final Examination in July 1938 was hailed as an immediate result (Education, February 1969, p. 4).

Also notable in the 1930s was the opening of Stewart House (1931), a charitable institution providing respite for needy children. A long planned for Federation House opened in Phillip Street in 1938.

War and Peace: 1940s to 1960s

By the end of the Second World War, 90 per cent of school teachers had joined the Federation, a figure which would increase to nearly 100 per cent by the end of the 1940s and remain there until 1972 when the Department ceased deducting fees from teachers’ salary cheques. Despite the war, the Federation engaged in an active program. Particularly significant was a new system of classification of teachers, achieved in 1943, which saw the advent of the Teacher’s Certificate. Professional certification and progression through annual increments of salary replaced the old system of classes through which teachers had to advance by examination and inspection. The early 1940s also saw formal affiliation with the New South Wales Labor Council and the Australian Council of Trade Unions.

Vitally interested in reconstruction after the war, the Federation and its members took interest in a large number of political and social questions. Policies included the demand for an Education Commission to replace the Public Service Board, pressure for changes to the Intermediate Certificate and the structure of secondary schooling, the provision of pre-school education, and the perennial questions of class size, facilities, and curricula. The Federation played an influential role in pushing for changes in post-primary school structure, curricula, and examination through the 1930s to the 1950s (Godfrey, 1988). Federation policy for pre-school education available to all children and under the control of the state Department of Education was never realised. In the 1940s the Federation began its campaign for federal funding to education.

While 1946 saw significant salary increases for teachers, women were still paid 80 per cent of the male salary. In 1949 an Equal Pay Committee was established with success finally achieved in 1959 when equal pay for women, phased in over four years, was agreed to by the Public Service Board. In 1954 the Teachers Health Society (now Teachers Health) was established to provide health insurance, and in 1966 the Teachers Credit Union (now Teachers Mutual Bank) was inaugurated. By this time, the Federation had purchased a site in Sussex Street to build a new Federation House, occupied in 1967.

Within the Federation, issues of the cold war era played out in internal differences and leadership challenges. Communists gained influence within the leadership in the late 1930s, and Sam Lewis held the presidency from 1945 to 1952 and then 1964-1967. In the early 1950s, the Federation campaigned against the Menzies government’s Communist Party Dissolution Act (1950) and urged a “No” vote in the 1951 referendum which sought constitutional power to the same end. Inside the Federation, however, members were bitterly divided on the issue and Sam Lewis’s first presidency came to an end in 1952.

The 1950s and early 1960s were characterised by continuing campaigns for federal funding, for the establishment of an Education Commission, and the reform of secondary education. All of these campaigns were widely supported within the 1950s union and thus enabled united action. In 1964, Commonwealth grants to State education began. This, however, proved a dilemma for the Federation, when the funding was directed to both government and non-government schools. Federal funding for non-government schools (state aid) and its allocation would remain a contentious issue for the following decades, through to the present day. The establishment of an Education Commission remained elusive, and in 1965 the Federation encouraged teachers to vote for the Liberal Country Party coalition in the hope that a new state government would deliver a promised Commission. The failure of the government to honour their promise caused a deep sense of betrayal. The Federation made a strong submission to the Committee Appointed to Survey Secondary Education (1953-1957) chaired by Harold Wyndham. Most of the recommendations of the Wyndham Report were implemented in the early 1960s.

With an increasing population, baby-boomers reaching secondary school age, and a growing retention rate of students in secondary schools, the problems of class size, accommodation and teacher shortages became acute. In this decade of widespread social change and unrest, a changed teaching demographic was observable. Young, well-educated teachers who had grown up in the relatively prosperous and optimistic post-war environment were ready to participate in militant action to achieve change. In 1968, the Federation called a one day strike.

1968

The Teacher’s Federation celebrated its Golden Jubilee in 1968, with pride in the range and significance of its achievements as recalled in the pages of its journal. For Elizabeth Mattick, Senior Vice President, the Federation’s celebration was the strike held on 1 October 1968. On 26 September meetings in five major centres passed a resolution calling on Council to call a one day stoppage. Mattick pointed to increasing discontent with the ineptitude of the Minister, the unsatisfactory conditions of work and growing concern for the educational progress of students as causes for this action. Council endorsed the recommendation and 1 October saw “one of the largest meetings in the history of unionism in this country …” (Education, December 1968, Supplement). Later in the day the teachers marched on Parliament House, completely closing busy Macquarie Street. Mattick claimed that 75 to 80 per cent of teachers refrained from work, and that the strike was supported by parents who kept their children at home. She concluded that the strike was successful and that “the Federation has emerged as a more unified, dynamic and respected organisation than at any time in the 50 years of its existence”.

First strike: Teachers at Wentworth Park, 1 October 1968. NSW Teachers Federation Collection, P5110

Not all parents, of course, supported the strike action of teachers, despite keeping children at home. Widespread community alarm and anger was expressed in the media at this radical action on the part of so many teachers. The debate on the rights and wrongs of teachers on strike was waged throughout the state and reached into nearly every home.

As well as listing major achievements of the Federation, the December 1968 Supplement to Education included community activities: “The welfare of children has been a constant cause of concern to teachers”. This contribution pointed to the establishment and maintenance of Stewart House, support of the United Nations Appeal for children in 1948 and recent support to Freedom from Hunger and Milk for India campaigns. The Federation’s moral and practical support for Aboriginal rights and educational opportunities for Aboriginal children was highlighted. The article concluded that the Federation had used its organised strength not only to advance the interests of teachers, but assist in achieving many other goals important to members as citizens. The Federation had “helped to mould the course of Australian history, not only in the field of education”.

Past President Don Taylor, in opening the Annual Conference of December 1968, addressed the proud history of the Federation, including the long years of campaigning for a secondary course of four years based on a core curriculum followed by two years of higher secondary education. Now that this policy had come to fruition, the nation needed to allocate the funds for its successful implementation. There were big tasks ahead for educators, he concluded, hoping that future years would continue to be beneficial “to the people in our schools, to the children, to the people of this State, and to the teaching service” (Education, February 1969, p. 3-4).