The belief that an academic education in home science would lead to the proper treatment of infants and children, better management of homes and improvements in the nation’s health motivated three philanthropists, John Studholme, Dr F.C. Batchelor and Dr Frederick Truby King in their efforts to establish a home science programme at the University of Otago. Like a number of progressive educators, they supported higher education for women. At the same time they advocated for women’s primary role as housewife and mother. Studholme, a philanthropist and Canterbury farmer, offered to fund a new school in Dunedin at the rate of £300 a year for the first four years and to provide £75 for a laboratory. A public meeting endorsed the proposal despite a warning from the Prime Minister who could ‘not see the necessity of including the ordinary operations of cookery or dressmaking in a university course’, and criticism from a number of women who expressed reservations about the motives of the proponents and concerns about the use of women as the objects of male ‘scientific study’.

Despite some opposition within the University Council, public support from the citizens of Dunedin along with offers of donation and a promise of a government subsidy tipped the balance in favour of the proposal. In June 1909 the University Council established a Chair of Home Science. Given the right to appoint the first professor, Studholme eventually offered the appointment to Winifred Boys-Smith, who had studied for the National Science Tripos at Girton College, Cambridge, and methods of teaching science and domestic science in the United States.

Higher education for women and home science

The establishment of a programme of Home Science at the University of Otago was also a response to the increasing numbers of women entering the ‘co-educational’ colleges of the University of New Zealand. As the first university college in New Zealand, Otago University had been established in 1869 in Dunedin—the capital of Otago—a province settled in 1848 by the Free Church of Scotland.

Figure 1: View of Otago University College, 1927. Godber Collection. Ref: APG-1589-1/2-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, NZ.

Influenced by Scottish educational traditions and egalitarian principles, the charter from the University of New Zealand included no explicit barriers to the entrance of women, and the first women who applied were received into classes with no difficulty. This was largely due to the efforts of Louisa White Dalrymple, the first principal of Otago Girls’ High School, who was a passionate advocate for women’s access to higher education.

In the early years, the University of New Zealand had relatively few students and Otago was happy to accept small numbers of ‘young ladies anxious for a little culture’ as a way of increasing the number of fee-paying students especially as most were, at least initially, not matriculated students. However the increasing number of women students wanting to enter the universities to undertake degrees presented administrators with a dilemma. On the one hand, the university was ostensibly a co-educational institution, with women freely admitted to all courses, on the other many contemporary educational administrators held conservative views about the dangers of women sharing classes with men. By creating a separate sphere for women students within an ostensibly co-educational institution, university administrators conformed to traditional Victorian attitudes to women.

Foundation of School of Home Science

In 1911 the School of Home Science opened with five students in a ‘tin shed’, which had formerly been the School of Mines. The teaching staff included professors from the medical school who taught the basic science courses ‘as for the Intermediate Examination in Medicine’ including physics, inorganic chemistry, bacteriology, biology and physiology and public health. From Professor Winifred Boys-Smith and her assistant (Gertrude) Helen Rawson students learned household business affairs, applied chemistry, practical cookery, needlework and hygiene. The curriculum emphasized the theory and practice of household science.

The main aim of these courses is to provide a thoroughly scientific education for women, in the principles underlying the conduct and organization of home life, in order to equip them well, and adequately, for the part they have to play. (Syllabus of classes for the degree & diploma in home science, c1911)

In the early years the School of Home Science struggled to establish itself in an inadequate building and with few resources. While the ‘tin shed’ provided the chemistry laboratory and a lecture room, cookery was initially taught at the North Dunedin Technical School. In 1912 Helen Rawson began to teach Home Science at the Training College, preparing students for their ‘D’ and ‘C’ certificates. (See Glossary.) The demand for teachers of Home Science in secondary schools and Manual Training Centres, the provision of bursaries for intending teachers and recognition of Home Science as a degree subject, all helped to attract students to the Home Science programme. By 1915 when the diploma course was increased from two to three years, there were thirty-two full-time degree and diploma students and three part-timers. By 1918 numbers had grown to sixty full-time students. A new home science building was opened in 1920, just before Professor Boys-Smith’s resignation. In 1921 Helen Rawson, lecturer in chemistry and economics, was appointed as Dean of the School of Home Science and Warden of Studholme House. In the same year Ann (Gilchrist) Strong accepted an appointment as Professor of Household Arts.

As Dean of the School, Helen Rawson taught the pure and applied chemistry classes and Household and Social Economics. All the lectures in Household Arts, Hygiene and Education and the supervision of practice teaching were undertaken by Professor Strong. The challenge of providing students with scientific courses of an appropriate standard while meeting the needs of the practical home science subjects was intensified by having to deal with inflexible university administrators. The issue of access to appropriate coursework in physiology—a programme designed for medical students and taught by medical lecturers—was the subject of a long-running dispute between Rawson and a Dr Malcolm in the Medical School. The problem came to a head in 1922 as a result of changes in the length of terms for medical students and difficulties faced by home science students who were unable to complete the course requirements in the allotted time. Eventually new schemes for the degree and diploma courses had to be drawn up with a three-year diploma coming into effect in 1921 and the four-year degree course in 1922.

Leadership of Ann Strong

With the marriage and subsequent resignation of Helen Rawson in 1924, Ann Strong took over as Professor and Dean of the School of Home Science. In Strong, Home Science found a leader with exceptional academic credentials and formidable administration skills. As one of the ‘Lake Placid Pioneers’ she had taken part in the historic Lake Placid Conferences (1899-1908), and in the 1908 formation of the American Home Economics Association. Educated at Bucknell University and Teachers College, Columbia, she was appointed in 1903 as Professor of Home Economics and Dean of Women at the University of Tennessee. In 1907 she was appointed Professor of Home Science at Canterbury College but had to withdraw on account of her marriage. In 1910 she was appointed Professor of the Home Economics Training School in Cincinnati, where she remained as Professor until 1917.

Figure 2: Ann Strong in 1936. New Zealand Free Lance : Photographic prints and negatives. Ref: PAColl-6388-29. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Strong was offered the appointment as Professor of Household Arts at Otago while working in India where she set up a training programme for graduates in Home Science at the University of Baroda, one of the first three universities in India to offer degree courses in Domestic Science. She presented a no nonsense approach in her dealings with male university administrators and stood her ground against interference from the Department of Education. It wished to make the education of home science teachers for technical and secondary schools the main focus of the degree programme. This proposal involved reducing the Bachelor of Home Science from four to three years so that students could undertake a one-year course at the Training College. Strong responded in her 1925 Report to Council, reiterating the need for rigorous academic and scientific standards ‘such as any University Course demands’ and defending the adequacy of teacher training in the existing course. She pointed out the need to expand the Applied Sciences and Household Courses that ‘prepare the student to carry out her working scientifically in the several departments of home life [so that they are able to respond]… to the conditions and requirements of the community’.

Strong’s struggle to maintain the integrity of the programme against the interference of University administrators and the Education Department illustrates a chronic problem in the field. By the 1920s strong traditional beliefs concerning women’s place were working to further the most conservative view of home science in both New Zealand and the United States. While Strong managed to protect the four year degree programme from capture by those who wished it to be linked more directly with the vocational training of home science teachers, her moves to comply with changing ‘labour conditions’ and ‘community’ demands for an expanded programme of practical household skills came at the expense of academic and scientific integrity. As a strategy, broadening the appeal of home science to respond to community expectations produced only short-term gains. The very flexibility that enabled Home Science to adapt to the changing needs of students and the community resulted in confusion.

Figure 3: Laundry class at Studholme, n.d. S07-518c-97-081/2 Hocken Collections, Archives & Manuscripts, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Carnegie Corporation interventions

The dilemmas facing the expanding Home Science movement in New Zealand are evident in the establishment of a University Extension Bureau in 1929. With the help of a five year grant from the Carnegie Corporation, a staff of three (two tutors and an office assistant) set up a very popular ‘Box Scheme’ for women in rural areas.

Staff from the Home Science School also contributed articles on ‘the aims and activities of the Home Science Extension Service’ and presented regular weekly radio broadcasts in the form of ‘lectures, stories, dialogues and playettes’. There was strong demand for the collection and publication of the recipes presented on the programme. However, Home Science’s role in promoting healthy living and effective home management practices among women’s groups merely provided more ammunition to those university administrators who continued to dismiss home science as ‘instruction in cookery, laundering and the purchase of household supplies’. At a time when universities were increasingly stressing the value of ‘pure’ research over ‘applied science’, the academic work of home scientists, work that involved the popularization of theories developed in social and natural sciences, became increasingly devalued.

Postgraduate pathways

Faced with these challenges Strong sought to advance the academic credibility of home science, to improve the qualifications of staff and to establish a post-graduate research programme. A recruiting drive to the United States in 1924 resulted in the appointment of Dr Lilian Storms, a graduate of Iowa State College who specialized in the Chemistry of Nutrition and Miss Gladys McGill, BSc M.A. a graduate of Teachers’ College Columbia University. At the same time Strong pushed for the establishment of a Master of Home Science degree to promote post-graduate research and to encourage graduates into advanced qualifications. This was established in 1926 and the first student to secure the M.H.Sc. was E. Neige Todhunter in 1928.

In the years 1928-1936 eight more students graduated with a Masters in Home Science. Strong also looked to her international colleagues to support the further education of recent graduates. Through connections with Dr Wickliffe Rose, President of the Rockefeller Foundation, she was able to secure the promise of three graduate fellowships. These were held in succession by Gladys Cameron, Olga Gloy and Enid Cauty. Gladys Cameron undertook research at the University of Chicago in 1924. Olga Gloy completed her Masters degree in 1925 and her PhD in 1927 at Columbia University, returning to assume the lectureship in Chemistry and Nutrition. Enid Cauty gained her Masters degree at Teachers College, Columbia University, before returning to teach in the Department of Foods and Cookery. In 1926 through the advocacy of Dr Lilian Storms and with the support of Strong, who was keen to develop a home economics extension programme at Otago, Catherine Landreth was offered an American Association of University Women (AAUW) scholarship at Iowa State College to undertake a Masters of Science in their agricultural and extension programme.

Figure 4: Chemistry of the household, School of Home Science, 1936. S07-518g-97-081/4.Hocken Collections, Archives & Manuscripts University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Other notable graduates included Elizabeth Gregory who obtained her Masters degree in Nutrition in 1929 before going to the United Kingdom and gaining her Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London in 1932. She went on to become Professor and Dean of the School of Home Science (1941-1961). This number of doctorates was impressive at a time when it was still common at universities in New Zealand and the United States to become a faculty member without a PhD.

The School of Home Science faced considerable difficulties building up and retaining qualified staff. These difficulties included the need for leaves of absence for further qualification of staff, temporary substitutions, and contemporary expectations that women would resign from positions upon marriage. While the school supported its own graduates into employment at Otago, many of those going overseas took up offers of employment with ‘better opportunities and salaries’ elsewhere. A case in point was Catherine Landreth who, prevented from returning to Otago by the failure of an expected position in rural extension teaching in 1927, went on to complete a PhD at Berkeley, University of California, before taking up a prestigious Laura Spelman Rockefeller Fellowship and shifting her field of interest from home science to the emerging field of child development. She was appointed as Professor of Home Economics and Director of the Nursery School of the Institute of Child Welfare at Berkeley in 1938.

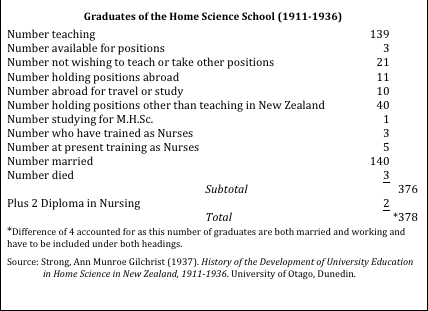

Those who graduated with a home science qualification from the University of Otago assumed a diverse range of roles within and outside the field of household science. Of the 588 students enrolled in Home Science during the period 1911-1936, 8 students graduated with a Masters in Home Science, 135 students completed the Bachelor of Home Science, 226 students completed the Diploma, 2 students completed the Diploma in Nursing and 129 completed the Group Course in Home Making. In addition to those securing degrees, 8 students travelled abroad on scholarships for post-graduate study; 4 gained their Masters and 4 secured PhDs. As Figure 1 indicates, 139 graduates of a total 378 entered the teaching profession, 40 were working in ‘positions other than teaching’, 5 entered the nursing profession (3 training as Nurses, 2 completing the Diploma in Nursing at the Home Science School). During the period 21 graduates moved overseas, 10 for travel or study and 11 to take up other positions. At a time when women relinquished paid work upon marriage, 140 are listed as married, although a footnote indicates that this number includes 4 graduates who were both married and working.

Home science graduates from the University of Otago took three main career pathways. Some like Ann Strong, made their mark as administrators and institution builders, others, like Catherine Landreth focused on academic research and there were many who pursued careers mostly outside university walls, as teachers, dietitians, demonstrators, lobbyists and specialists in fields such as health nursing. In many ways these graduates were typical of the growing numbers of single and the small numbers of married women who, in the early decades of the twentieth century, were able to use their higher education to pursue careers in the public sphere. A home science qualification offered them employment opportunities that allowed them to perform pioneering work in the field and to open avenues for other aspiring women professionals.

Glossary

Five classes of Teachers Certificate were described by the letters A, B, C, D, E, ‘A’ being the highest and ‘E’ the lowest grade. Class C and D passed a variety of compulsory subjects via Departmental examination, Matriculation, or University papers in order to teach at primary level.