Jean Muir was born on 14 July 1919, to a family that was rising from the working class. After overcoming the difficulty of a father who opposed any more than elementary education for girls, Jean Muir was able to progress beyond Lloyd Street Higher Elementary School in Melbourne. She spent four years at the academically selective University High School (1933-1936). There she developed her love of English literature, but also economics and economic history. She did very well in secondary public examinations which enabled her to enrol in an honours arts degree, her main subject stream, economics, at the University of Melbourne.

Muir was a student at the university from 1938 to 1940. The year 1937 had been occupied as an assistant teacher at Hawthorn Primary School. Her delayed university entrance had been forced by the want of a scholarship and her father’s intentions for her. She had much success academically at the university, but as significant was her student political activity. She was an office holder in the Labour Club, her success there underwritten by her membership of the Australian Communist Party (ACP). Her presidency of the club was made especially difficult from 1939 by the pact between Stalin and Hitler, and the subsequent banning of the Communist Party in Australia in 1940. It was at the University of Melbourne that she met Dick (Gerard) Blackburn, son of Labor member of the federal parliament, opponent of military conscription and civil rights lawyer, Maurice Blackburn. Dick’s mother, Doris Blackburn was a pioneering feminist, peace movement activist and later, member of the federal parliament.

After a year working for the Economics Department at the University of Melbourne, Jean Muir was employed by the federal Department of War Organisation of Industry, under Minister John Dedman. He would later have ministerial responsibility for planning Australian post-war reconstruction. Jean Muir thrived on the policy work associated with the Department. She had multiple responsibilities including research, public relations and writing speeches for the minister. As a clerk, she was paid a male wage. Women were not expected to be employed as clerks in the federal public service so there was no female rate of pay. Muir remained a communist, but she was certainly swept up by the optimism of many public service policy makers and intellectuals at the time. They believed that interventionist governments could develop economy and society in ways that could make for a more secure, socially just and strong Australia.

Figure 1 Jean Blackburn in 1943, recent economics graduate and employed in the federal Department of War Organisation of Industry. Photo courtesy Susan Blackburn.

In 1943 Muir married Dick Blackburn. She resigned from her public service job following the birth of the first of her three children in early 1945. Marriage and children meant a new life centred in Adelaide, where her husband was employed as a soil scientist by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). Jean Blackburn led a rather discontented suburban life, initially divorced from paid work altogether and the government policy work she knew she had a talent for. In the late 1940s and early 1950s she was occupied by Communist Party sponsored organisations. She led the New Housewives Association branch in Adelaide, and as the 1950s continued, became increasingly involved in the peace movement.

The year 1956 was important for Blackburn. The revelations of Stalin’s crimes at the beginning of the year, the attempt by the Australian Communist Party to suppress their discussion, along with her belief that the commitment of the ACP to the peace movement had been compromised once the Soviet Union developed its own atomic weapons of war added decisively to her longer term discomforts. This included resentment of the way she had been treated when the New Housewives was summarily disbanded by the ACP in 1950. She left the Communist Party, being confirmed in her decision by the succeeding suppression of the Hungarian Revolution, also in 1956. She remained a socialist, linking with Helen Palmer’s Outlook magazine and associated study groups, and other former ACP members who had either been expelled from or left the party of their own accord. Blackburn developed her sense of independence. Her husband remained in the ACP and was critical of her departure, but from 1954 she had re-entered paid work. She was employed by the Presbyterian Girls College in Adelaide as a teacher of history and economics. The South Australian Education Department would not employ her unless she accepted an appointment anywhere in the state. This was not possible with young children.

Feminism and Australian Wives Today (1963)

From the 1940s Jean Blackburn had been reading the feminist classics. She was a member of the Council for Women in War Work. She was involved in International Women’s Day as an organiser and participant from the 1940s. She began writing about the injustices of married women being confined as “housewives” for the Outlook magazine, leading to an invitation from the Victorian Fabian Society to produce a tract on the issue. With the assistance of a friend, she produced a remarkable argument on the multiple injustices that occurred for women, children and men if married women were excluded from the workforce. As part of her argument she insisted that older married women should have access to higher education. This came to fruition in the Labor government led by Gough Whitlam (1972-1975). Australian Wives Today preceded the full emergence of second wave feminism later in the 1960s. It consolidated Blackburn’s position as a bridging figure, from the feminism of the 1930s to 1950s, to that of the 1960s to 1990s.

The South Australian Karmel Report (1971)

Figure 2 Jean Blackburn working on the SA Karmel inquiry, 1969. Photo courtesy Susan Blackburn.

With the baby boom of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the emergence of the demand that secondary education should be accessible to all youth, the pressures on State governments’ education departments were severe, not only in terms of resourcing, but administrative practices and educational cultures. A Liberal Country League government in South Australia asked the Vice Chancellor of the recently founded Flinders University to conduct an enquiry into South Australian education. Peter Karmel was an economist and, like Jean, a former student of the University of Melbourne. Following advice from fellow university economists he asked Jean Blackburn to work for the enquiry. She had recently completed a Diploma of Education as its top student, and had been quickly employed in government teachers colleges.

From 1969 to 1971 she worked on the enquiry, conducting much of the research and administration, and writing the first and final drafts of many chapters in the report. The report covered many areas, among them advocacy for the teachers colleges becoming colleges of advanced education, the development of comprehensive high schools and suggestions about the work schools might do in areas marked by the poverty of families.

Karmel reported to a new Labor government led by Don Dunstan. By the time of the Report reform was already under way as a new Minister of Education (Hugh Hudson) and Director-General (A. W., “Albie” Jones), began the transformation of the highly authoritarian and centralised practices of public education in South Australia. The South Australian Karmel Report was noticed by the leader of the federal Labor Party, Gough Whitlam.

Schools in Australia (1973), the Australian Karmel Report

Immediately following the election of the federal Labor government in early December, 1972, the Prime Minister, Whitlam, asked Karmel to chair an interim committee to produce a report that would be the basis for establishing an Australian Schools Commission. The price of Karmel’s agreement was that Jean Blackburn should be deputy chair of the Interim Committee.

The urgency of researching and writing the report brought Blackburn to live in Canberra for some months. In May 1973 the Report was published, with its recommendations for the Schools Commission, and the schools funding it should supervise. It represented the largest and most decisive intervention by the federal government in Australian schools since federation. Blackburn was acknowledged as the principal philosophical and policy inspiration behind the report, though without the confidence of Karmel, such a role would not have been possible.

Figure 3: The report on which Jean Blackburn laboured, establishing the structures and policy directions for the new Schools Commission, 1973

The Report never envisioned that schools should be directly supervised and run by federal government agencies, including the Schools Commission. The idea was that the federal government would fund capital and recurrent grants to school systems and sectors, public and non-government. Special programs would fund educational innovation, libraries and disadvantaged schools for example. The effort put by grant-seekers into winning and keeping grants was the main means by which the Schools Commission would reform Australian school education.

Not all of the intentions of the Report came to fruition. The government did not control the Senate, and eventually Commonwealth funding of resource-rich (wealthy) schools was one of the prices paid in order to get enabling legislation passed at the end of 1973. The government also made another compromise in terms of the principle objective of funding being the support and improvement of poorer schools and communities. The Catholic Church was given block grants to administer. A consequence was that system expansion rather than the funding of the poorest schools often occurred. Blackburn considered that both of these compromises diminished the potential of the Schools Commission to support its social justice objectives.

Blackburn and the Schools Commission

Jean Blackburn was one of the two full-time Commissioners, along with Ken McKinnon as full-time chairman. By all accounts the Commission members worked well together. Jean found a natural ally in one of the part-time commissioners, Joan Kirner, a parent organisation representative from Victoria. McKinnon relied on Jean for significant writing tasks, including drafting the philosophical and broad policy direction statements in the triennial reports.

Blackburn was a major publicist for the work of the Schools Commission, addressing a great range and number of conferences and other educational and community gatherings. Like all the Commissioners, but in her case more so because she was full-time, she contributed to the work of the Commission across the broad range of its responsibilities. The vast archive of her papers in the National Archives of Australia attests to this role.

Her major responsibility was to set directions for and supervise the Disadvantaged Schools Program, but she also had responsibilities on behalf of the Commission for Victoria and South Australia, as well as the programs and projects that addressed special education and migrant and multicultural education.

She concluded her role as Schools Commissioner in 1980. After the initial years with the Whitlam Labor government she was rather less enamoured of the role the Fraser Coalition government envisaged for the Commission. There was inadequate funding for the programs Blackburn was committed to as spending re-oriented towards creating markets in education, within and between government and non-government schooling sectors. Parental school choice as well as the encouragement of a growing non-government schools sector became more important than the original Karmel and Schools Commission aims for the equitable funding of education, directing funds to the schools and systems that had the greatest difficulty in providing equality of opportunity in education.

Blackburn’s major Schools Commission responsibilities

The Disadvantaged Schools Program (DSP)

The DSP under Jean Blackburn’s leadership developed a distinctive approach. Schools would apply for the funding of projects that would improve the educational experience of young people in disadvantaged schools. The approach was different from sister programs in the United Kingdom and the United States where remediation of literacy and numeracy deficits in individual students was often the target (usually described as “compensatory education”). Blackburn sought longer-term school and teacher transformation, indeed, community development. In taking this approach the Australian program was innovative and distinctive. Blackburn travelled to the UK and USA to study their approaches and delivered a substantial paper to an OECD meeting in Paris in 1979.

Figure 4 One of many Disadvantaged Schools Program committees. Shirley Randell, federal Director (third from left, seated) and Jean Blackburn (second from right, seated). Photo courtesy Shirley Randell.

In the same year, the Commission published her discussion of the educational funding of disadvantaged schools, Title I and the Disadvantaged Schools Program. The program itself had committees that processed school applications for funding in each State of the Commonwealth. This ensured a decentralised approach, often with distinctive state and regional characteristics. The program was successful though evaluation in conventional terms was always a problem. The things that could be measured (for example improvements in literacy and numeracy) could not indicate to more than a minor degree the achievement of the broader objectives of the program.

Girls, Schools and Society (1976)

This report had a very great influence on the policy and practice of education in schools as it affected girls in particular. Blackburn played a crucial role in drafting the final text of the report and managing the affairs of the committee responsible for its production. (Its generation, contents and influence are the subject of a separate entry in this Dictionary.)

Schooling for 15 and 16 Year-Olds (1980)

Blackburn played a major part in the supervision, organising and writing of this report. It brought together the best thinking available to the Commission on what ought to be provided for young people as they entered senior secondary education. The context was rising unemployment, especially youth unemployment, and the necessity of secondary schools providing suitable curricula for all youth in the post-compulsory years. Senior secondary schools were to provide for universal youth attendance. They were no longer to imagine themselves as narrow portals providing qualified students for little other than the universities and other higher education institutions.

Blackburn extended her thinking to senior secondary curriculum, believing that vocational and academic approaches to schooling needed to be reconciled. This was a difficult problem with a long and contentious history, but it prepared her for her major post-Schools Commission assignment in Victoria. As part of the research for the Schooling for 15 and 16 Year-Olds project, Blackburn along with other Commissioners visited a very large number of schools with senior secondary establishments in all Australian States.

After the Schools Commission

Jean Blackburn was in high demand as a speaker and writer on education policy in the years following her employment in the Schools Commission. Twice she was a keynote speaker for the national conference of the Australian Women’s Education Coalition, though her feminist approaches were not appreciated by everyone, especially at the second meeting. Apparently she argued too strongly that the education of boys as well as girls, should be of concern to all educators. She participated, along with Dean Ashenden, Bill Hannan and Doug White, in the writing of the Manifesto for Democratic Curriculum, published by the Australian Teachers Federation in 1984.

Blackburn often addressed graduation ceremonies in universities. She received several honorary doctoral degrees. She was appointed first Chancellor of the new University of Canberra in 1990. She also led planning for the Centenary of Women’s Suffrage (1894-1994) in South Australia, but her major new work in education after the Schools Commission occurred in Victoria.

Chair of the Ministerial Review of Post-compulsory Schooling, Victoria, 1983-1985

The new Cain Labor government in Victoria was keen to make its mark in education. Jean Blackburn was appointed chair of the review of post-compulsory schooling in Victoria. The chances that her report would satisfy all stake-holders was low given the divisions between government technical and high schools, government and non-government schools, multiple teacher unions, let alone the various institutions that sought the development of senior secondary completion credentials to suit their own purposes.

Blackburn was able to hire Helen Praetz to work for the Enquiry following the publication of her insightful work on youth unemployment in Victoria. With the cooperation of a steering committee, less so the working committee, Blackburn published a discussion paper in 1984. This was followed by extensive, exhaustive and state wide community and stakeholder consultations.

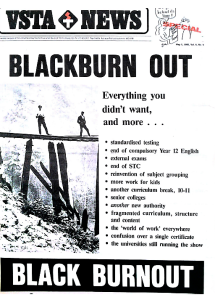

Figure 5 The VSTA teachers union objects to Jean Blackburn’s report to the Victorian government, 1985

The final report was published in the next year. Well received by the government, it was excoriated by one of the teacher unions in particular, the VSTA (Victorian Secondary Teachers Association). The main problem seems to have been the Blackburn Report’s recommendation that senior secondary colleges be established, in effect radically reforming the former Year 7-12 high and technical schools. This recommendation had some effect eventually when rather than independent establishments, secondary schools in a district contributed students to senior colleges within their schools grouping.

Other recommendations that were more easily implemented included a new universal completion credential for secondary schooling, the VCE (Victorian Certificate of Education), and a compulsory unit within it, a study of work and society which eventually emerged as Australian Studies. The great problem of too many small schools without the resources to offer more than a very restricted curriculum was addressed, but it was a future Liberal government led by Geoff Kennett that closed many such schools.

The work and society curriculum unit did not survive as a compulsory study for more than a few years, but Jean invested a great deal in its efficacy as one way of solving the dilemma of the divisions between vocational and a more academic education. The subject was to contain a substantial study of “work” in the economy and society more generally and could certainly include student work experience placements and guidance. Later, and for the national Curriculum Development Centre, Jean wrote her The Study of Work in Society: A Curriculum Proposal (1987).

The last years

Jean Blackburn sustained her contribution to feminist thinking and organisations not only through chairing the Centenary of Women’s Suffrage Committee in South Australia. She had supported women’s studies in South Australia and the women’s research centre at the University of Adelaide. Nevertheless her effort declined as she grew older, and as her health sustained multiple set-backs. She also found it difficult to formulate satisfactory approaches to education policy reform in the context of neoliberal approaches to economy and society as they influenced Labor and Liberal governments alike in the late twentieth century. She survived the death of her husband, Dick, by a little more than two years, dying on 2 December, 2001.

The achievement

Among her many achievements, Jean Blackburn was:

Figure 6 Blackburn as foundation Chancellor of the University of Canberra, 1990-1991. Photo courtesy University of Canberra.

(1) an inspirer of the first progressive and social-justice reform program in education of any consequence for federal governments during the twentieth century;

(2) a co-author of an effective report on gender inequality in education and its reform that had a remarkable impact on governments, schools and teachers across Australia;

(3) the philosophical and administrative heart of a disadvantaged schools program which to this day impresses with its focus on community development rather than narrow student skills acquisition;

(4) a curriculum warrior who believed that the basics, literacy and numeracy acquisition, were too mean as the sole goals of curriculum reform: schools needed to teach the world, students’ place in it, and how to make the world a better place;

(5) a powerful advocate that effective teacher development should occur on a whole school basis, whole school improvement would lead to longer-lasting benefits for the education of more children;

(6) a producer of argument that the older centralised, authoritarian and assimilationist approaches to public education in Australia, needed radical revision: schools were not to be detached outposts of the state managing unruly children, unruly parents and unruly communities: schools had to work with communities;

(7) a prime mover for the reform of older approaches to senior secondary curriculum, with new curricula and credentials that gave all young people a chance, and the new curricula had to have intellectual worth—none of the “keep them quiet and busy” approach that warehoused and betrayed youth as unemployment grew.

Jean Blackburn was a pioneering policy-maker of significance at state and national levels. She was the first woman to write a major report on education for any government in Australia. Her commitment to the crucial significance of education and schooling in the struggle for social justice made her a leader in Australia’s great period of education reform from the 1970s, and a significant critic in 1980s and 1990s as neoliberal inspired policies in education undermined social justice as a principal objective of reform.